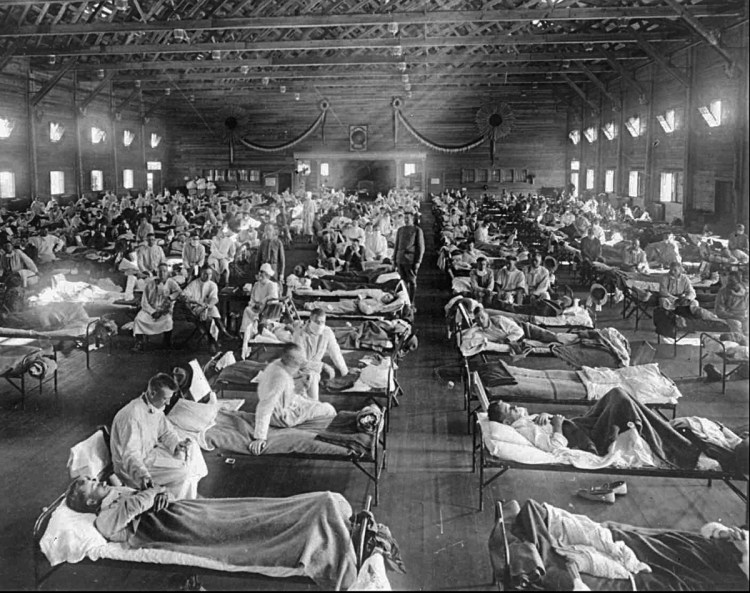

One hundred years ago this week, Pvt. Albert Mitchell, an Army mess cook stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, received the very first diagnosis of a new strain of influenza that eventually infected approximately 500 million people across the globe – about one-third of the world’s population – and led to at least 50 million deaths, far more than the lives lost in the still-raging World War I. The Spanish flu pandemic brought new urgency to the quest to comprehend infectious diseases and the way they work, but the subject is still beset by scientific challenges and popular misunderstandings. Here are five of the most tenacious.

Myth No. 1: A pandemic on the scale of Spanish flu is unlikely today.

After the outbreak of H1N1 – or swine flu – in 2009, the World Health Organization (WHO) warned that “the world is now at the start of the 2009 influenza pandemic.” Many researchers questioned that finding, with Philip Alcabes announcing in these pages that “we’ll never see another flu outbreak” like the Spanish flu. Some said the WHO was unnecessarily raising anxieties; others suggested that the agency had been unduly influenced by the pharmaceutical industry, which would stand to make money in preparing for and treating an outbreak. A headline in Frontiers in Public Health held that medical advances have made it “Unlikely That Influenza Viruses Will Cause a Pandemic Again Like What Happened in 1918 and 1919.”

And it’s true that we’re much better than we were a century ago at detection and containment, we have antiviral drugs that save the lives of some infected patients, and the 575,000 lives that swine flu took were a small fraction of the Spanish flu total.

But most global health experts agree that it’s only a matter of time before a combination of risk factors makes us vulnerable to another pandemic. We may even be overdue. Unlike in 1918, a disease can cross the globe in a fraction of the time it takes to show symptoms and before health officials realize that a crisis is brewing. And increasing urbanization worldwide, alongside weak health systems, means vulnerable people are living on top of one another. That’s the tinder epidemics need to explode.

Myth No. 2: Most healthy adults don’t need the annual seasonal flu vaccine.

In the United States, just over 40 percent of adults get the seasonal flu vaccine; the number is higher for children but still less than 60 percent. And it’s true that, in a good year, the vaccine is about 60 percent effective; the efficacy of this year’s cocktail has ranged as low as 25 percent for some strains.

Still, the seasonal flu vaccine remains the best way to prevent infections. It also creates herd immunity, stopping the disease’s spread when a critical mass of people get vaccinated. Some protection is far better than none.

Ideally, as Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health and other researchers have recently argued, we’d replace the annual seasonal flu vaccine with a more effective universal one that would cost much more to develop but result in permanent immunity. Unfortunately, manufacturers, which benefit from the current $3.3 billion seasonal flu vaccine market, have little incentive to invest in a universal vaccine that would protect against all forms of influenza. Several members of Congress recently proposed $1 billion to fund research for this.

Myth No. 3: Some of the deadliest pathogens don’t pose an immediate risk.

It’s easy to think that measles is no longer a threat, since the CDC declared that it had been eliminated from the United States in 2000. But between the CDC declaration and 2014, the annual number of reported measles cases in the United States ranged from 37 to 667. In this country alone, about one in every 20 children with measles gets pneumonia, one of every 1,000 gets encephalitis, and one or two out of 1,000 will die. Unless we’ve eliminated measles – and, for that matter, other infectious diseases such as polio and diphtheria – everywhere in the world, Americans will remain susceptible to them. Viruses travel.

Another error some epidemiologists make is to focus on the near crisis at the expense of the far one. Ebola, for example, is an incurable, often-lethal malady with no licensed vaccine, but it’s hard to transmit from person to person and an unlikely candidate for a pandemic. It is a mistake to treat it with so much urgency that we fail to neutralize other potential threats.

Myth No. 4: We need bigger vaccine stockpiles to neutralize disease outbreaks.

Logistical and economic challenges limit the size of any vaccine stockpile. Plus, it’s a complex business to get it just right. Egg-based vaccines, for example, are hard to scale up quickly; vaccines have a shelf life; and producing large quantities of vaccines that may never be used can be expensive and can take scarce resources away from routine immunization. Rather than focus too much on stockpiles, government and nongovernmental organization money would be better spent helping struggling countries immunize their populations to prevent infection. They should also build health systems capable of detecting and responding to outbreaks before they spread further – the objective of a CDC global health initiative that’s now in danger of downsizing.

Myth No. 5: Barring people from disease-affected countries will keep the nastiest bugs out.

At the height of the Ebola outbreak in 2014, a number of American public figures urged closing U.S. borders to travelers from the hardest-hit West African countries. “The bigger problem with Ebola is all of the people coming into the U.S. from West Africa who may be infected with the disease. STOP FLIGHTS!” tweeted Donald Trump, then a private citizen. At least 85 members of Congress agreed, the Hill reported.

Such responses rarely work; pathogens don’t respect borders. Also, cutting off contact with outbreak-affected countries can compound the problem by grounding supplies and personnel they need to fight the spreading disease. Most countries already take precautions to ensure that potential pathogens don’t cross borders, such as subjecting travelers to thermal temperature scans at ports of entry.

Still, there’s no real substitute for preventing outbreaks at their source, through routine immunization, improved surveillance and other proven public health measures.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.