SCARBOROUGH — In the spring of 2017, University of New England professor Noah Perlut downloaded the first videos from a game camera he’d hung low on a tree just off the Eastern Trail near the Nonesuch River in order to record the wildlife living nearby. Later, from his office, he looked at the images the camera captured over a two-month stretch. He was surprised at the first species he observed in the video, waddling through the woods: a pair of wood ducks foraging on the forest floor.

“I was predicting more common terrestrial species like gray squirrels or turkey,” Perlut said. “A relatively rare migratory duck searching for acorns surprised me. I do not think we have had any other wood ducks since.”

Two years and tens of thousands of images later, Perlut is ever more interested to learn what surprises await in the data that comes from his game-camera study. It’s scheduled to be completed in 2021.

The Gap Tracks Project – believed to be the first study of its kind in Maine – uses two game cameras placed around an existing section of the Eastern Trail to the south of the Nonesuch River and six cameras in the now-wild, 1.6-mile stretch of woods to the north, where the trail will be continued this fall. Perlut will continue to gather still photos and videos from the cameras after construction on the new section begins, while construction is underway, and for one year following the completion of the new section. For now, this missing section of the trail is called “the gap;” the new construction will connect the trail to the north, which winds through South Portland, with the trail to the south, which makes its way through Scarborough Marsh. Until the new section is finished, bikers and walkers must continue to get off the trail briefly and ride or walk along Black Point Road to Highland Road.

Once these two sections are connected, this part of the Eastern Trail will be a continuous 17-mile foot-and-bike path from South Portland to Saco. All told, the 65-mile off-road trail from South Portland to Kittery – 23 miles of which has been built – is part of the 3,000-mile East Coast Greenway, which one day will extend from Calais to Key West, Florida.

A red fox running through the woods in Scarborough is seen by a game camera in use for a study being conducted by UNE Professor Noah Perlut. The Gap Tracks Project, which uses game cameras on and around the Eastern Trail, is expected to be completed in 2021. Photo courtesy of Noah Perlut

On the face of it, the Gap Tracks Project studies the effects of urban sprawl. Biologists believe that when human development encroaches on wildlife habitat, it drives wild animals into smaller, fragmented swaths of woods, fields and marshland, making it harder for wildlife to forage, mate, raise young, and generally flourish. But Perlut and other biologists aren’t certain the new section of trail will completely displace the wildlife. Perlut said it may only change the behavior of wildlife that’s already there.

Many wild animals in Maine, both diurnal and nocturnal, adapt to living around humans but often go undetected, said Maine Wildlife Biologist Brad Zitske. A frequent viewer of the Gap Tracks Project’s photos and videos, Zitske was amused at the photo of a coyote with “someone’s chicken” and a coyote carrying a groundhog almost half its size.

“This is as suburban as Maine gets, so this is a really cool opportunity to see what wildlife we have living in our backyards,” Zitske said. “There’s quite a suite of animals there. So much of the time as a regional biologist, my work is involved in nuisance wildlife. It’s nice to have photos of wildlife being wildlife.”

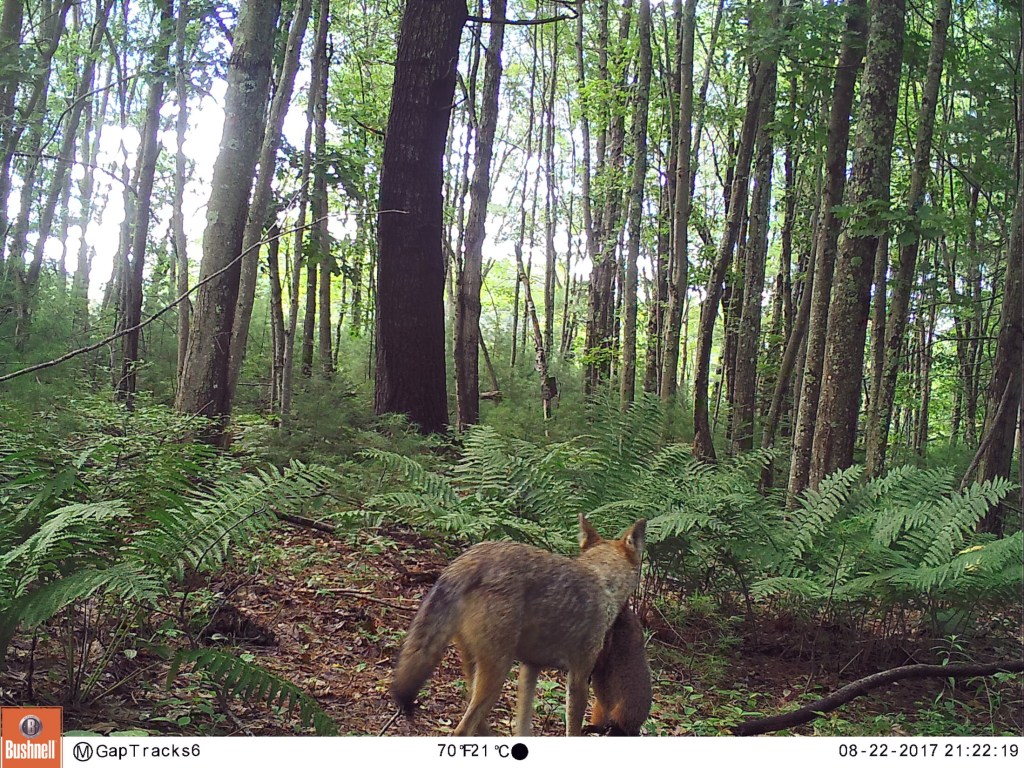

A coyote carrying a groundhog is captured by a game camera in use for The Gap Tracks Project. Photo courtesy of Noah Perlut

Zitske said he would expect to see the trail disrupt wildlife to some extent, especially since people bring dogs on the trail and dogs running off leash often harass or harm wildlife. But he said exactly how the new section of trail will affect wildlife remains to be seen.

“There could be wildlife that doesn’t care,” Zitske added. “That will be one of the interesting questions the study helps answer after the trail is completed.”

Zitske said simply informing people what animals use the marsh is useful – especially when you consider that Scarborough Marsh, the largest salt marsh in Maine, lies smack in the center of the state’s most developed area in York and Cumberland counties, home to 37 percent of the state’s 1.3 million people. According to a 2018 study by the Eastern Trail Alliance, the nonprofit that is building the Eastern Trail, more than 250,000 people used the trail last year.

Meanwhile, the game cameras have photographed turkeys, deer, skunks, coyotes, fox, bobcats and 44 other species of wildlife around the trail. Perlut gathers photos and videos from his eight cameras once a month. Sometimes there are just 40 photos on a camera, other times several thousand. The motion-detection cameras take two quick pictures after movement trips them, followed by a 10-second video.

The data won’t be fully analyzed until the study is completed. But one thing is already clear: On the existing section of the Eastern Trail, wildlife most often forage at night, when few people are about to disturb them. In contrast, on the wild section, the camera regularly captures some species – such as turkey, deer and red fox – during the day.

Scientific studies documenting the species that use this urban, yet wild, 3,100-acre marsh are relatively new, said Linda Woodard, who has directed Maine Audubon’s Scarborough Marsh Nature Center for 30 years.

This year for the first time, Woodard will set up three game cameras and two bat monitors in the marsh. For seven years, she has conducted a bird monitoring survey using volunteers and university professors who write down what they see to send to e-bird.com, a national scientific database run by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. She has collected a similar inventory of insects.

These surveys have provided some new information – such as the fact that least sandpipers prefer to forage in the upper marsh, while semipalmated sandpipers prefer foraging closer to the ocean. In the three decades she has run the Audubon center, Woodard said only two changes have been so dramatic that they were obvious without conducting any studies: the rising water levels and the declining numbers of bats.

“When I first gave full-moon canoe trips, I always had bats overhead picking off mosquitoes. Now if I see one bat, I’m lucky,” Woodard said.

Perlut’s study will help paint a more complete portrait of the health of the marsh.

“He caught a fisher on film. In my mind, a fisher is really a woodland animal,” Woodard said. “That surprised me.”

Professor Noah Perlut looks at photos on a laptop after retrieving them from one of his game cameras near the future Eastern Trail extension in Scarborough. Derek Davis/Staff Photographer

The Eastern Trail Alliance has done surveys of human activity along the trail – but no wildlife surveys, said Carole Brush, the executive director of the trail’s management district, which works with the 13 municipalities that are along the Eastern Trail. Occasionally, she gets a wildlife report of note: a coyote seen in South Portland, a black bear crossing the trail in Arundel. But providing an inventory of wildlife along the Eastern Trail will be eye-opening for the many people who use the trail, she said.

Perlut is curious to see what mammals are documented after the new section is completed, and also to see how humans respond to his inventory of animals after the study is published.

“Some people might not come out if they know bobcats and coyotes are here. I hope not,” Perlut said. “(The trail is) certainly better than building a Walmart.”

___________________________

CORRECTION: This story was updated at 6:26 p.m. on May 6, 2019, to correct a quoted reference to fishers and to clarify the foraging activity of sandpipers.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.