There’s a baker. A veteran. An activist. An urban farmer. With its everyone-welcome philosophy, the Occupy Maine encampment has attracted people from all walks of life, with myriad stories about what, exactly, has drawn them to Lincoln Park and what they hope to accomplish.

Inside the iron fence that rings the park, campers can get food, medical attention, companionship and shared purpose.

But for every person who drives by and honks their horn in solidarity, is another yelling at them to get a job. They are vilified as lazy, anti-capitalist, sentimentalist or unable to understand how the real world works.

They say they are the real world, and that’s why they are there. Here are some of their stories.

‘Occupy is a state of mind, a state of being’

Heather Curtis, 42, had just returned from the Common Ground Fair this fall when she came down with the flu.

Stuck at home, she surfed the Web and discovered the Occupy Wall Street movement. When she learned a related group was coalescing at Monument Square in Portland, she baked an apple “Occu-pie” and joined them.

“Coming together and getting set for winter is a real way of providing clarity. It’s a crucible,” she said.

Curtis has been living in Portland for 11 years, moving here from the midcoast. She makes small purses out of old neckties, what she calls “repurposing the corporate noose.”

Her teenagers have decided to stay home rather than join her in the tent she has set up near the park fountain, where she has been sleeping for about a week after visiting the encampment daily. As she talks, a couple strolls into the park, arm in arm, and asks where to make a financial donation. They say they support the occupiers even if they don’t stay there.

“Occupy is a state of mind, a state of being, a state of heart,” Curtis tells the couple. “You don’t have to be physically present here.”

‘My job gets stopped and I’m unemployed’

Randy Santa Cruz, 55, has spent the past two weeks with Occupy Maine. He was returning from a three-week construction job as a laborer in Connecticut when he stopped in to check it out.

“I had been following the occupation when it was just in Wall Street,” Santa Cruz said. “It was great. They were finally doing something to address the problems we’re having. … I think we have to tip the scales a little bit back at least.”

Originally form Kansas, Santa Cruz has been living in Jonesport and Lubec — commercial fishing, raking blueberries, collecting edible snails — working to get by while the construction industry lies dormant. Early in the recession, Santa Cruz had been hired to work on a 40-story casino hotel in Connecticut, but after the foundation went in, the job was put on hold. The project would have employed thousands, who would have been able to support their families, he said.

He watched in the aftermath as banks got rescued and investment bankers got bonuses.

“My job gets stopped and I’m unemployed. It just seems like a slap in the face,” he said. “I’m angry.”

Santa Cruz helps run the kitchen and has been impressed with how generous donors have been.

As he talks, a cyclist whizzes by and shouts “Sidewalks are for walking, not standing.” Santa Cruz says many people are supportive but some yell out criticism.

He’s aware that not everyone in the camp has the same commitment to its ideals.

“There are some here that are the lost, some that come in from other camps,” he said. “They’re suffering from a system too.”

‘We don’t need people telling us what to do’

John Schreiber, 27, was a senior in high school in Connecticut when the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks happened.

“A lot of people were worried. I was worried about what we do in response,” he said. When the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003, he was studying natural resource management at the University of Connecticut and joined a camp set up in the middle of campus in protest. He came to Portland in 2008.

“I’ve been involved in nonhierarchical organizing,” he said. “It lets you do what you’re comfortable with and what you can. … We don’t need people telling us what to do.”

A baker at Rosemont Bakery, he stops in after work each day and on his days off. This week, he’s spending the week in the Occupy campsite because he is on vacation.

As he talks, Schreiber works to replace a fuse in a volt meter, used to check the charge in car batteries that power a few lights and some laptop computers used to access the Internet.

“I’m concerned with economic justice. It’s sickening that the top one percent make huge fortunes without contributing anything to society while we work and sweat,” he said, adding that he does not believe developing sham financial instruments contributes to the betterment of society.

‘This isn’t a summer camp or a campground’

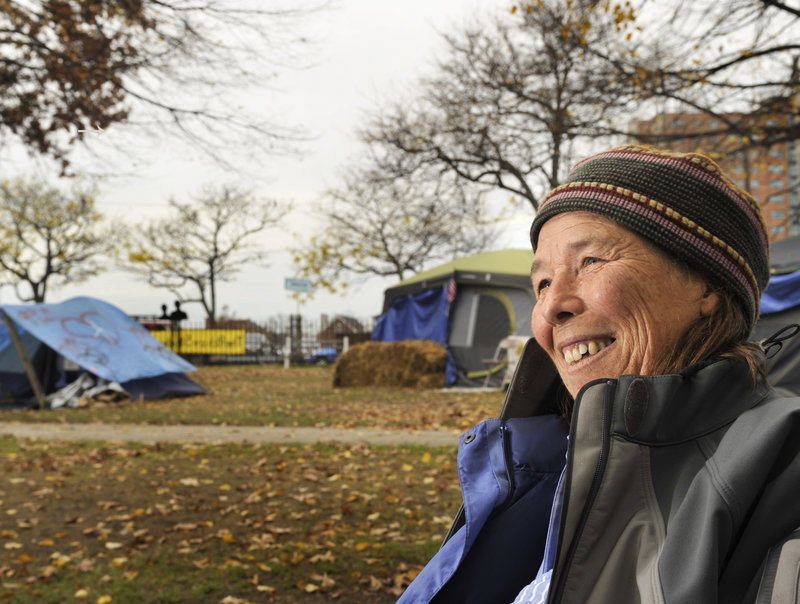

Palma Ryan, 59, sits at the camp’s information desk, alongside a poster board of upcoming activity and a few pieces of literature.

Ryan was raised in Massachusetts and has lived in Portland for five years. She has an apartment on High Street, but she has been sleeping in the camp for four weeks, after spending three weeks camping at Occupy Boston.

“When I heard about Occupy Wall Street I thought it was the greatest idea that had come down the pike in 25 years. … I’ve been an economic justice advocate all my life. Any time a good idea comes up for planetary survival, I jump on it,” she said, noting she also supports efforts to stop global climate change, or in this case, drawing attention to the wealthiest one percent in the country.

Ryan said she tries to keep the focus on the protest, one of the reasons she volunteers to staff the information table. The group’s calendar of activities also appears online at OccupyMaine.com, she said.

“I keep having to remind people, ‘This isn’t a summer camp or a campground.’ It’s political. It’s a constantly evolving situation. It’s an occupation.”

‘Money is corrupting our political system’

Steve Demetriou, 55, is a commercial photographer who also writes for local weekly newspapers, but he said he came out of the corporate world.

Demetriou worked at Idexx Laboratories in the 1990s when it was a relatively small company, but as it grew and went through a series of restructurings, he took a voluntary severance package. He is from South Portland and now lives a couple blocks away from Lincoln Park.

“I have been following what has been happening to the middle class for years,” he said, highlighting the writings of Elizabeth Warren, a bankruptcy expert and popular author on economics who is running for the U.S. Senate in Massachusetts.

He worries about the unequal distribution of wealth and what he says is a broken health care system and was prodded to political activism by a series of events: the invasion of Iraq, the U.S. justification of torture and what he describes as the theft of the presidency by George W. Bush in 2000.

“Money is corrupting our political system,” he said.

The launch of Occupy Wall Street followed by Occupy Maine led him to conclude: “Finally these issues are coming to the fore, because they just haven’t been.”

‘People are smiling and pumped up to be here’

Bree Hietal, 26 and Kevin Boyd, 25, of Brooklyn, N.Y., arrived in Maine after visiting Occupy encampments in New York, Boston and Burlington, Vt.

“We’re fighting for social and environmental justice, rather than corporate greed,” Hietal said. “I think it’s time for the people to get their rights back with regard to land and food.”

Hietal and Boyd described themselves as advocates of intensive urban farming in abandoned inner-city lots.

Boyd worked for a nonprofit in Brooklyn but has been unemployed for the past month. Hietal worked for a fashion designer in New York before leaving to tour Occupy sites.

“In New York, there’s like 250 people in the park and there’s like 50,000 who come through during the day,” Boyd said. “That was really exhilarating, high energy, a lot of ideas being shared.”

When the couple showed up in Portland this week, Occupy Maine demonstrators showed them a good spot, on a bed of pine needles, to set up their tent, said Hietal, as she ate from a bowl of split pea soup.

“This movement is just kind of indivisible from homeless rights,” Boyd said. “We don’t have a place to stay.” At the encampment, “we have somewhere to stay and people look out for each other here.”

“People are smiling and just pumped to be here,” Hietal said. “It kind of pumped us back up on the whole Occupy movement.”

‘I’ve had a strong work ethic all my life’

Mike Jacobs was watching reports about the Occupy Wall Street from his home in Augusta when he decided to come to Portland to join Occupy Maine.

He has spent the past week and a half at the camp and just recently moved out of the community tent into a donated tent, lined with donated blankets.

Jacobs moved to Maine to be closer to his family in Millinocket but settled in Augusta to be close to veterans services.

A 50-year-old, Jacobs enrolled in the Marine Corps and was in Japan and the Philippines but was not involved in combat, he said. He was eventually discharged because of “authority issues,” he said cheerfully.

Afterward, he worked for the next 25 years at a variety of jobs: cooking, detailing cars, landscaping. Now, after two back surgeries and torn rotator cuffs on each shoulder, he is disabled, though looking for part-time work.

“I’ve had a strong work ethic all my life, never called in,” he said.

Jacobs said his personal issue is to see better services for the country’s returning veterans.

“We have 40,000 troops coming home. Services for veterans are stretched thin as it is and are being cut left and right,” he said, adding that many of the returning servicemen will have issues that need addressing.

Fighting for himself ‘as an occupier’

“Big John,” who would not give his last name, said he has been living in Maine for three and a half years since moving from Georgia.

“My job got outsourced out of the country to China,” he said of his work as a customer assistance representative in a call center in Georgia.

John, 34, has also worked as a part-time chef but has been out of work since being incarcerated in connection with an alleged assault. He said the charge was false and he successfully defended himself in court.

When he lost his job four years ago, he fell behind on his mortgage payments and eventually lost his house, he said.

That experience drew him to the Occupy movement.

He decided to “get in this situation and fight for myself as an occupier” and has been staying at the Lincoln Park campsite since its initial days, he said.

John has a booming voice that can be heard across the encampment, and at times he can be heard arguing with others in the group. He said he has been asked to tone down his rhetoric and not be too hostile.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.