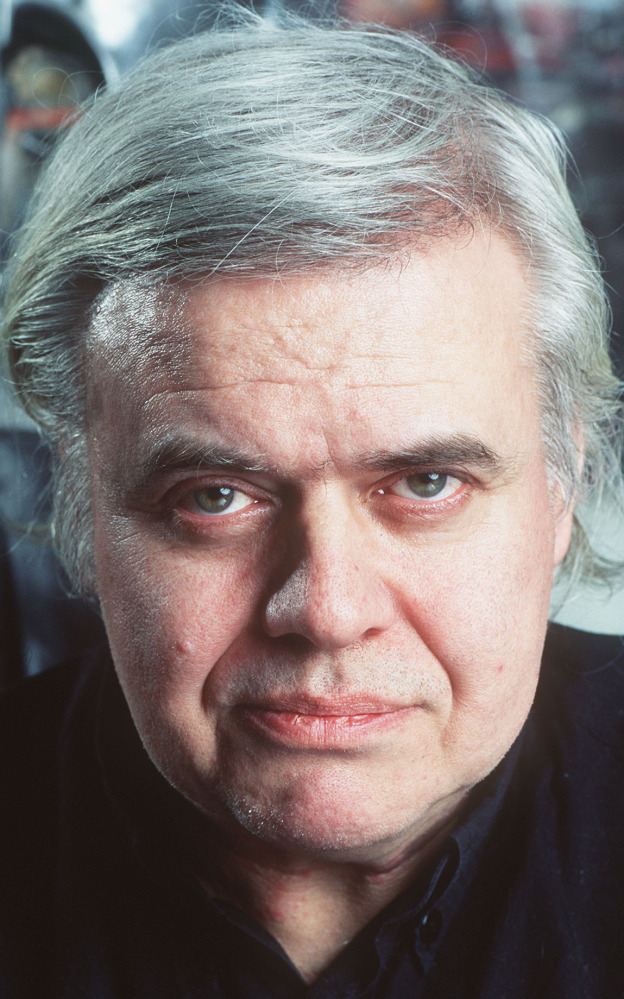

H.R. Giger, a Swiss artist who designed the nightmarish creature that takes over a spacecraft in Ridley Scott’s 1979 film “Alien,” attacking the helpless crew in what has become one of the most admired horror and science-fiction movies of all time, died May 12 in Zurich. He was 74.

He had injuries from a fall at his home in Zurich. Members of his family confirmed his death.

Giger’s surrealistic monster – part dragon, part machine, part erotic fantasy – helped “Alien” win an Academy Award for best visual effects. His eyeless monster is a vision of pure malevolence, with an elongated head and neck, a powerful tail and two pairs of jaws with tyrannosaurus-like teeth.

It was a “perfect organism,” in the words of the doomed spacecraft’s science officer, played by actor Ian Holm. “Its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility.”

Before directing “Alien,” Scott had seen a copy of Giger’s 1977 book, “Necronomicon,” a collection of elaborately drawn artworks of otherworldly figures, fusing mechanical and biomorphic shapes. Giger’s images, often painted by airbrush, have a way of evoking terror and dread, of being revolting and seductive at the same time.

“I nearly fell over,” Scott told London’s Daily Telegraph newspaper in 2012.

One of the producers of “Alien,” after seeing Giger’s art, reportedly said, “This man is sick.”

But when Scott received the assignment to direct the movie, he immediately knew his designer would have to be Giger: “I’d never been so certain about anything in all my life,” he said.

The film, based on a story by Dan O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett, takes place aboard the Nostromo, a commercial spaceship returning to Earth in a future century, with tons of minerals. Also on board are slowly incubating eggs, one of which hatches into the alien creature. In its fully adult form, the monster was portrayed by a 7-foot-2 student wearing a specially made costume.

“Alien” was only the second feature film for Scott, who went on to direct “Blade Runner,” “Thelma & Louise” and “Black Hawk Down.” It made a star of actress Sigourney Weaver and in 2008 was ranked by the American Film Institute as the seventh-best science-fiction film of all time. But, in a real sense, the movie’s most dominant character was Giger’s unsettling creature.

“I loved the script, but on one level it was a B-movie,” Scott told the Newark Star-Ledger in 2003. “The monster has to be great, otherwise, you haven’t got a good film. We got a great monster, and I never questioned anything else.”

Hans Rudolf Giger was born Feb. 5, 1940, in Chur, Switzerland. He said he had a carefree childhood, but he did deliver leeches for his father, a pharmacist, and often visited a local museum that displayed a mummy.

Giger studied architecture and industrial design at a college in Zurich and became a full-time artist in the 1960s, influenced by the surrealist painter Salvador Dali, fantasy artist Ernst Fuchs and the horror fiction of H.P. Lovecraft.

Giger’s longtime girlfriend and frequent early model, Swiss actress Li Tobler, committed suicide in 1975. A later marriage to Mia Bonzanigo ended in divorce.

Survivors include his wife, Carmen Scheifele-Giger, who is the director of a museum devoted to Giger’s art in Gruyeres, Switzerland.

In addition to his work on “Alien,” Giger also contributed designs to “Poltergeist II” (1986), “Alien 3” (1992) and “Species” (1995). He and Scott revisited the “Alien” franchise in 2012 with the film “Prometheus.”

Giger was inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame in 2013 and has been a lasting influence on filmmakers, science-fiction painters and tattoo artists. He also designed furniture, jewelry and the interiors of two Swiss bars that bear his name.

He created many album covers, including Emerson Lake & Palmer’s “Brain Salad Surgery” (1973) and Debbie Harry’s “KooKoo” (1981), as well as a custom-built microphone stand for Jonathan Davis, lead singer of the heavy-metal band Korn.

In a rare interview, Giger said he was once stopped by customs agents in the Netherlands who thought his paintings of body parts and other hyper-sexualized images were photographs.

“Where on earth did they think I could have photographed my subjects?” he said. “In hell, perhaps?”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.