Most Mainers are likely to see the rate they pay for electricity fall again in 2017, but that doesn’t mean their total monthly bills will be much lower.

That’s because while the price of fuel that drives New England’s wholesale electric market has moderated in recent years, the costs of upgrading transmission lines and building new power plants is trending upward.

Despite that, Maine’s relatively flat costs contrast with other New England states, where electric bills have gone up 20 percent over the past several years.

That picture was emerging Tuesday after the Maine Public Utilities Commission accepted a bid for supplying energy to homes and small businesses that are served by Emera Maine’s Bangor Hydro District and buy their electricity through the state’s standard offer.

The PUC is set to announce Wednesday which bid it has accepted in Central Maine Power Co.’s service area, and experts anticipate that it will be similar to the Emera-area deal.

The new Emera-area rate, which goes into effect Jan. 1, will be 6.3 cents per kilowatt hour. It represents a decrease of 4.6 percent. For a typical eastern Maine home that uses 500 kilowatt hours a month, that translates into $31.63 a month next year, a savings of $1.52.

This welcome news is offset by Emera’s transmission and distribution costs, which are notably higher than the cost of supplying energy. While the typical monthly supply cost next year will be $31.63, charges for transmission and distribution add up to $56.03, for a total bill of $87.66.

The standard offer is the default rate for customers who don’t sign contracts with a competitive energy provider.

The new rate is only for the energy-supply portion of electricity bills, not the distribution services provided by Emera and CMP. Under Maine’s 17-year-old electric restructuring law, utilities only distribute power, they don’t generate and sell it.

LOW COST OF OIL, NATURAL GAS HELPS MAINE

Electricity supply rates in New England are largely dependent on the wholesale cost of natural gas, which is used by power plants to generate roughly half the region’s electricity. Except in 2013 during a cold winter that caused gas prices to spike, supply rates generally have been falling for a decade. They slid from roughly 10 cents per kwh in 2007 to 6.6 cents this year.

For a typical home in southern Maine that uses 550 kilowatt hours of electricity a month, that means the energy portion of the bill has come down from $55 a decade ago to $36.30 this year.

Continued low prices for oil and for liquefied natural gas, which supplements the region’s pipeline supplies, will benefit New England next year, said Rich Silkman, chief executive officer at Competitive Energy Services, a Portland firm that helps companies and institutions manage energy costs.

“We don’t see a whole lot of change in the larger, national gas market,” he said. “We think the market is very stable.”

Against that backdrop, the cost of electricity to power Maine homes has been moving in the right direction.

“Maine has made some modest progress,” said Patrick Woodcock, who heads Gov. Paul LePage’s energy office.

Lowering Maine’s above-average electric rates is a priority for the LePage administration, but current supply cost trends are the result of market forces and state mandates elsewhere, not Maine-centered policies.

Woodcock cited data that shows Maine’s residential electric bills have essentially been stable since 2010. During that time, bills elsewhere in New England have gone up 20 percent, and they rose 10 percent nationwide. That’s because of long-term contracts and the elevated cost of renewable energy in southern New England, he said, as well as the national shift from coal to natural gas.

TRANSMISSION, POWER PLANT COSTS RISE

Woodcock, who is stepping down from his position next month, said Maine could still work to lower supply costs by continuing the push for more natural gas pipeline capacity and by modifying well-meaning policies that encourage renewable energy production, although at a high cost.

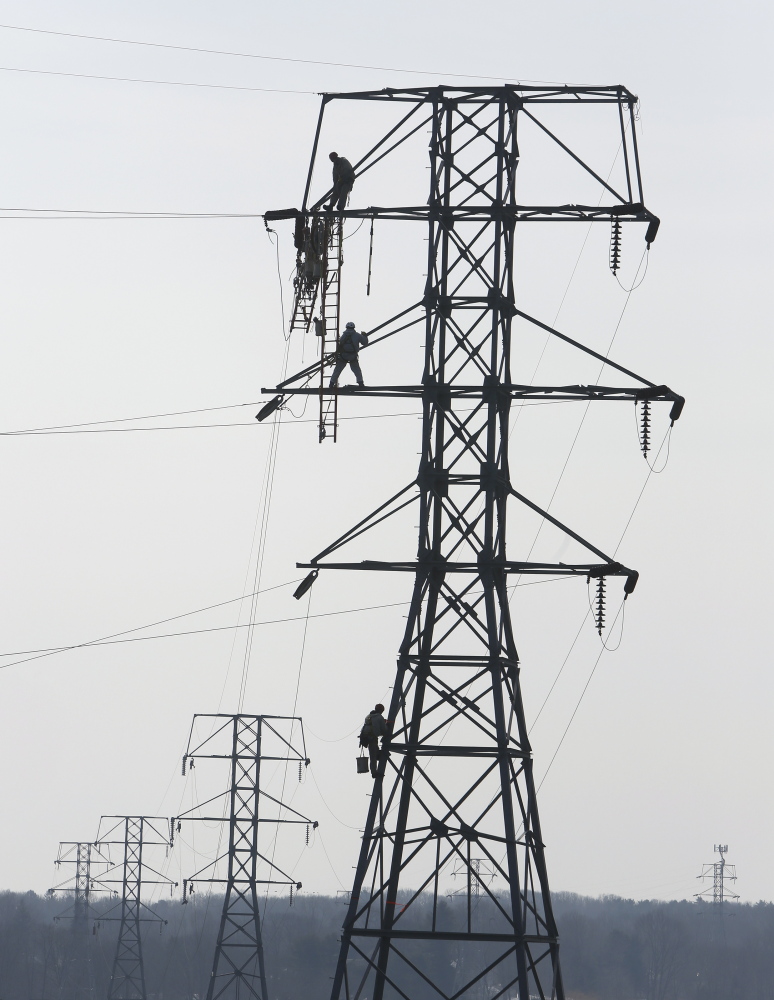

But any further dips in energy supply rates will be tempered by recent investments in upgrading transmission lines.

The biggest example is CMP’s five-year, $1.4 billion Maine Power Reliability Program. That cost was spread across New England, but it and other transmission upgrades are the principal driver of increases on CMP’s portion of the electric bill.

For a customer using 550 kilowatt hours a month, CMP’s charges have risen from $36.17 in 2007 to $46.15 this year.

“We do need to invest in the system to keep it reliable,” said Gail Rice, a CMP spokeswoman. “Our bulk transmission system hadn’t seen a lot of love in nearly 40 years.”

An additional factor raising the cost of all power bills in New England is capacity payments. These reflect the price of building new power plants to make sure the grid has enough capacity to meet demand. Several older power plants have closed or are set to shut down. And with energy costs low, power-plant owners receive special payments to make it profitable to be on line.

These market forces are bringing the rates that most Mainers pay for electricity closer to the national average, a goal of the LePage administration.

UNLIKELY TO MATCH NATIONAL AVERAGE

Taken together, Maine home customers paid an average of 16 cents per kwh in 2016, according to federal statistics. Maine has the lowest residential electric rates in New England, where the average is 18.2 cents per kwh.

But the national average is 12.9 cents. And in Southeast states, where coal and government-subsidized hydro and nuclear power are in the mix, the average residential rate is 10.6 cents.

“It’s not likely we can reduce supply costs more to bring us much closer to the national average,” said Tim Schneider, Maine’s public advocate. “In New England, we are seeing historically low energy prices.”

Maine, Schneider said, is being hurt in two ways by transmission costs. Besides paying some of the highest costs in the country, closings at paper mills and other big manufacturers are spreading the fixed costs over fewer, smaller customers.

“There’s no silver bullet, particularly on transmission costs,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story