CONCORD, N.H. – After days of torrential rain in March and April, water wouldn’t leave the basements of about 15 homes in a Rollinsford neighborhood. The pumping seemed endless, and officials in the Seacoast town needed a solution.

They found it with the New Hampshire Geological Survey office, which had a detailed map pointing out sand and clay layers underground – and an explanation for the continued flooding.

It showed a unique situation where the sand deposits were overlying clay layers, and the water could not percolate down,” said David Wunsch, state geologist. “So the basements were flooding and the sand was flowing into the basements because residents were pumping the water so hard, and the foundations were being undercut.”

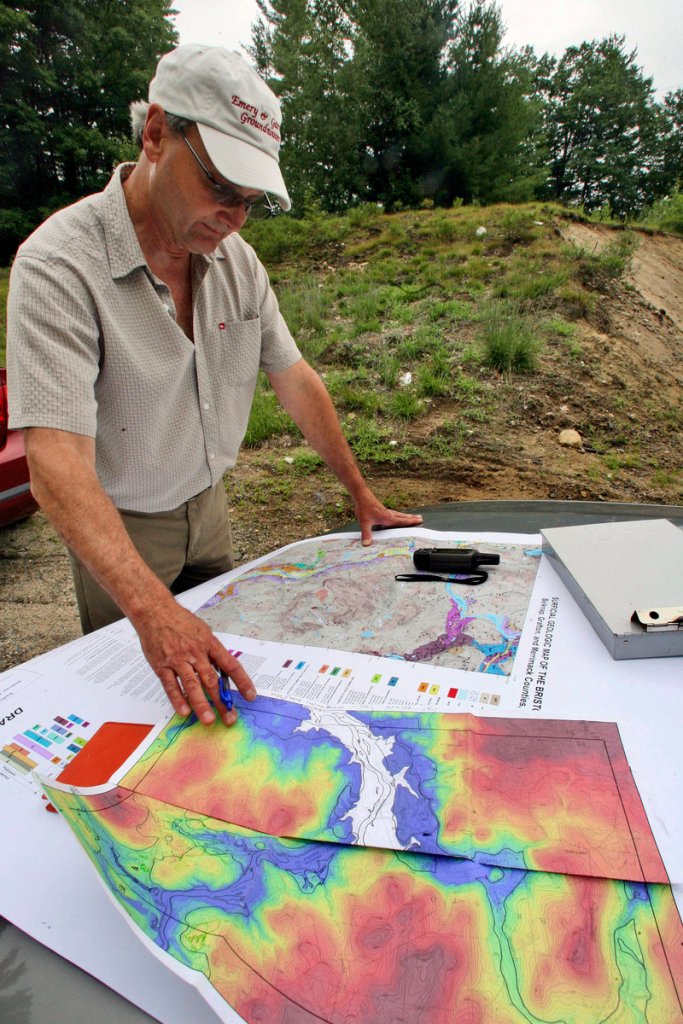

Geologists have been working on detailed mapping of materials beneath the surface since 1992, when a state-federal program was created. New Hampshire, which has geologists working in all or parts of 21 towns this summer, is approaching the halfway mark in creating such a topographical map but says it might be another two decades before the work is done.

Such maps can help in engineering and construction projects. They tell people where they can dig for wells, or know whether their wells may contain arsenic. They can show if their land has huge sand and gravel deposits, or if they want to know where groundwater is and how to protect it. The maps can show areas susceptible to sinkholes and landslides.

States decide which areas they want to focus on in the maps, which carry a level of detail like that seen on hiking maps.

New Hampshire has covered most of the southern part of the state and is working north. So far only one state — Kentucky — has been fully mapped because it had extra assistance in past years to assess its coal resources, said Randall Orndorff of the U.S. Geological Survey, associate program coordinator of the U.S. mapping program. Other states, like Alaska and Hawaii, have done very little mapping.

States compete for federal funding and are limited to what they can match. Wunsch, past president of the Association of American State Geologists, said each state can get up to $300,000 a year for the project. New Hampshire, which has faced its share of budget cuts, including the loss of its mapping program manager last year, has averaged about $70,000 in recent years.

The geologists may carry GPS navigation units, hand augers to create holes in the earth, small shovels and specialized compasses. Many of the materials are deposits formed by glacial melting thousands of years ago.

“We interpret where these ice positions were as the glacier melted through the area,” said John Brooks, a Meredith geologist who is mapping the Holderness area these days.The hardest part of the mapping is trekking through areas that don’t have roads or trails, Brooks said: “It can be very physically demanding.”

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.