Museums are often awkward places – awkward to get around in, and awkward in which to show art. It is a common affliction, and the grand and glorious Portland Museum of Art is no exception.

I’m serious about the grand and glorious – the PMA is the museum building of my heart – and I’m also serious about its awkwardness. After a quarter-century of perambulation, I still get lost trying to exit its second floor. And its inner byways, culs de sac and tiny harbors confuse my finely tuned male sense of geometry. I’m always bumping into something I’ve already seen.

God forbid I should have to look at something twice in one day.

These trivialities lead me to the museum’s great central hall. I’m tempted to call it a rotunda, but it isn’t rotund. It is, however, a magnificent, soaring indoor piazza, a place of awe. I mean it.

It is also a clumsy place to show art. I mean that too. Between the hall’s traffic, its interior commercial activities and the urgencies of its architecture, it’s a wonder that anything on its walls has the stamina to survive. Contemplation is out of the question.

A test of this would be the number of times that work installed in the hall has been written about. Offhand, I can only think of a pair of early paintings by Greg Parker and the hermit’s retreat of a couple of biennials ago.

The other day, I noticed a powerful Ellsworth Kelley on a lofty perch in the great space. I wonder how often that sighting will be repeated. And I wonder, too, whether the architect in his heart intended that his great walls be interrupted by works unworthy of their scale.

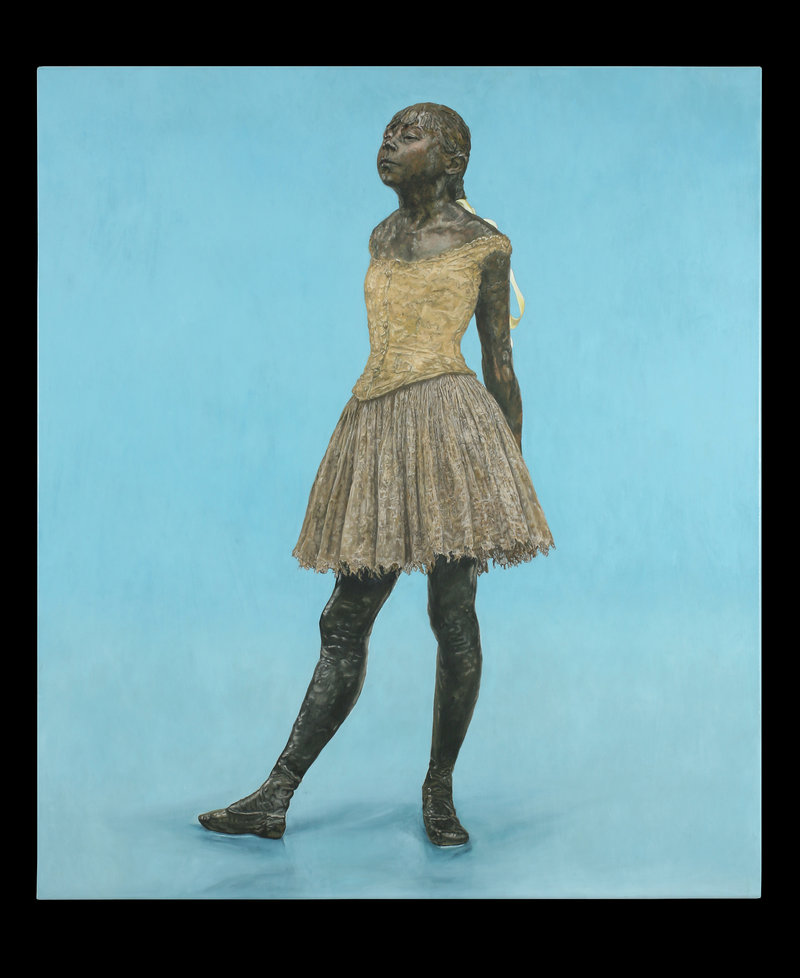

All of this brings me to a group of handsome paintings that don’t meet the demands of the space, but the enchantment of whose subject offers them unlimited clemency. The artist is Jane Sutherland, and the subject is Edgar Degas’ sculpture “La Petite Danseuse De Quatorze Ans.”

The English version, “Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer,” is an injustice to the ethereality of Degas’ accomplishment. You know the piece; it’s about 99 centimeters high and presents a young ballet dancer, the lift of whose chin, the interlacing of whose hands behind her arched back and the advanced and turned position of her right leg endow her with an insouciance that has made her immortal.

(For the record, her name was Marie van Goethem, and as a muse, she transcends time. Her embedment in our culture will linger forever.)

The wall text that accompanies the paintings advises that the small sculpture it praises is a fusion of opposites: Elegance and awkwardness, reserve and impudence, fragility and confidence all through her perfect balance. I agree. It is so emotionally exquisite that it rises above any limitation that the term “exquisite” implies.

The piece has a complex technical history – wax, plaster and bronze – and inevitably, some dispute as to its physical history. I’ve seen it at, I think, the National Gallery, and, in its innocence, it is charismatic. You see it, and you feel elevated.

I am not surprised that Sutherland is enchanted by the Little Dancer and, as I have said, her paintings of the work are quite beautiful. She has provided three principal renditions: One with a blue ground, one with a blue ribbon on a tangerine ground, and one with a rose ground.

Each is from a different view, and my choice is clearly the version with the tangerine ground. The extension and turn of the figure’s right leg from that perspective is a small miracle.

The paintings are accompanied by a suite of four large charcoal drawings. Their annotative quality and animation do not suit the sedate refinement of Degas’ vision as generously as do the paintings.

Sutherland’s paintings raise an issue that interests me. They are not images of Mille Marie; rather, they are images of images — that is, pictures of a sculpture. It is one thing to take a natural image and directly reduce it to two-dimensional form. Our culture accepts the adjustment easily, and we go through the transition each time we enter a painting gallery. There, we accept the fact that while a painting may simulate the real, it is in fact a step away from it.

We do the same with a work in sculpture, although the sculptor’s problem is different and infinitely more difficult than that of a painter. Implying animation through a three-dimensional form is perilous.

However, implying animation to a two-dimensional version of a sculptural representation of a natural form is three steps from the source, and is so odd that it seldom works.

Why paint about sculpture? What will it reveal? Does it work in Sutherland’s case? Yes, because Degas’ form – the young dancer – is a realization by him of a painter’s vision and not that of a sculptor, and so Sutherland is closer to the source than she might otherwise be. In short, her painting probes the vision of another painter. Her affection for the form is apt and touching. I sense Sutherland is very close to the work, and it doesn’t hurt to have Degas on your side.

Of course, you should also see “Edgar Degas: The Private Impressionist” while you’re at the PMA. Among the array in that show is an ephemeral drawing of Rodolphe Bresdin by his pupil Odilon Redon. Bresdin was a small figure, but there are those who love him. I fancy myself among those few.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 46 years. He can be contacted at:

pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.