At first blush, Julia King’s middle-school classroom at D.C. Prep Public Charter School seems like any other middle school. Seventh-graders are busy reviewing math skills that they struggled with on a recent test. Walls are plastered with motivational posters. But look more closely. Something else is going on here — something that would have seemed more familiar to these 12- and 13-year-olds’ great-grandparents.

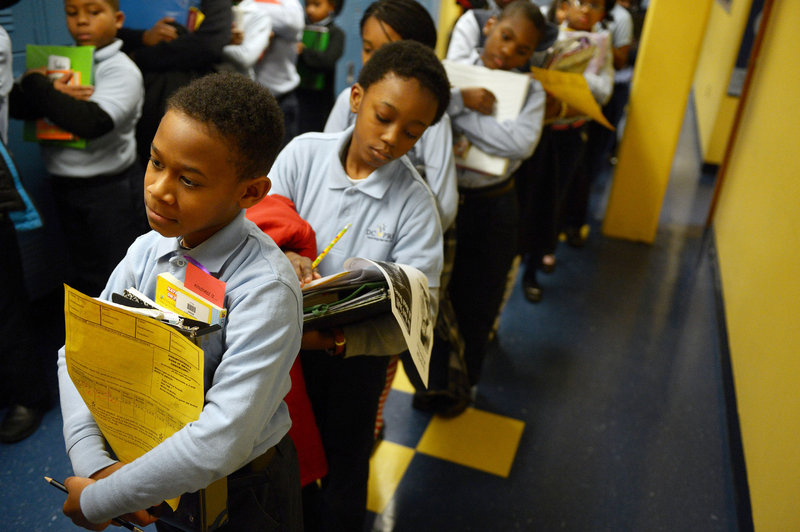

Fourth- through eighth-graders at this Washington, D.C., school are expected in their seats by 8 a.m. No excuses. The children do not speak in the hallways or classroom unless spoken to by a teacher. They navigate the hallways single file. Throughout their eight-hour school day, they bring to each class charts on which they record, as the teachers decree, behaviors, both good and bad, listed on a key. This key lists 26 behaviors, A through Z. Failure to meet any of them results in detention.

During a math review, King, 2013 D.C. Teacher of the Year, blurts out: “Responsible ‘R.’ I see that you are listening.” On cue, students scribble an “R” beneath a column reading “RESPONSIBLE Behaviors.” Before class is over, King’s students will have also written an “I” for staying on task and a “B” for getting the teacher’s attention appropriately. At the end of class, students file out in silence. Two boys wearing green mesh pinnies over their navy-blue polo shirt leave last. They are serving in-school suspension.

The boot-camp expectations, the behavioral charts, the pinnies, all point to a calculated attempt to teach students self-discipline, focus, accountability — ultimately, self-control. Schools across the country are responding to a growing body of research that suggests a definitive and disturbing link between low levels of self-control in childhood and serious problems later in life.

It’s hard to believe, but letting kids throw punches or text-message their days away or blow off academics can lead to a slew of mental and physical health woes in adulthood. Terrie Moffitt, a pre-eminent researcher in self-control, observed in a groundbreaking study that the need for self-control in 21st-century America is “not just for well-being but for survival.”

As it turns out, our emotional lives matter as much, sometimes more, as our intellect in the path to success. And schools are exploring ways — from character-based education to mindfulness meditation to social emotional learning — to teach the challenging, essential ABCs of self-control.

STUDIES DATE FROM ’60S TO PRESENT

The study of self-control began in the 1960s with a marshmallow. The longitudinal Marshmallow Study (as it is still known) started at Stanford University and operated on a simple premise: Offer 653 4-year-olds a marshmallow, and tell them that if they waited to eat it after the researcher returned from leaving the room, then they could have a second one. If they couldn’t wait, they were stuck with just one.

The study in delayed gratification revealed that the marshmallow resisters scored much higher on their SATs and, as they aged, remained thinner, less prone to drug addiction and to divorce than their counterparts who couldn’t master their salivary glands.

A spate of studies appeared in the past three years or so, particularly the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, and, almost overnight, the stakes seemed higher. The Dunedin study — headed by Moffitt and Avshalom Caspi, Duke University psychology and neuroscience professors — followed 1,000 New Zealanders over 32 years, beginning at birth. What researchers observed in this study, published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2011, was astounding.

Children as young as 3 who showed lower self-restraint were much more likely to face future struggles with high cholesterol and blood pressure, periodontal disease, chronically empty savings accounts, debt and single parenthood. Those with less self-restraint had much higher incidences of drug and alcohol dependence. And “43% of least disciplined children had a criminal record by age 32, compared with just 13% of the most conscientious.” If this isn’t disturbing enough, “one generation’s low self-control disadvantages the next generation,” the researchers stated.

One worrisome fallout of lack of self-control is cheating. A 2012 study of 23,000 high school students found that 51 percent admitted to cheating on an exam. Conducted by the Center for Youth Ethics at the Josephson Institute, a nonprofit group that oversees the widely used Character Counts curriculum, the study also found that 20 percent admitted to stealing from stores and 76 percent said they had lied to parents about “something significant.” But that’s not the worst of it. In a 2010 version of the study, which is conducted every two years, 57 percent agreed with the statement that “In the real world, successful people do what they have to do to win, even if others consider it cheating.”

CHARACTER-BASED EDUCATION

For many educators, the straightening of such disturbing swerves in integrity is found in character-based education. Once the philosophical flesh of Catholic and fundamentalist Christian schools, character-based education is creeping into the public sector.

At schools such as D.C. Prep, whose classrooms are largely filled with at-risk students, risk-taking means creating an environment where students start thinking about college in fourth grade. DCP administrators are too aware of the alarmingly high numbers of poor students who make it into college only to drop out. To this end, DCP has recruited teachers from middle- and upper-middle-class backgrounds who know what it takes to make it in college. This translates into a school day that runs from 8 to 4, teachers on call until 8 p.m., and resources for graduates that few middle schools provide. Graduates can return for evening study halls twice a week, as well as counseling for college and financial aid applications.

This rigor also means behavioral expectations tinged in a Puritanical scarlet. Or green, in this case. Remember those students wearing green pinnies? They were suspended and still had to attend classes. They could not utter a word the entire day — nor could anyone speak to them — as they were banished to the back of the classroom and to the end of the hallway line.

Such measures surely seem extreme. But Ibby Jeppson, DCP’s director of resource development, insists that the school teaches students an “agency over their own lives” and a better understanding of the “expectations of the broader culture” they hope to someday enter. “Yes, we sweat the small stuff around here,” Jeppson says.

In an e-mail, Jeppson says that the message needs to be clear to students and parents alike: “The small-stuff expectations are linked to important life skills: being on time, being dependable and being there every day, dressing appropriately.”

MINDFULNESS MEDITATION

Perhaps the fastest-growing technique in classrooms for teaching self-control begins with “om”: mindfulness.

Mindfulness uses meditative breathing and focus to increase awareness of body and mind, and to decrease stress. The technique, borrowed from Buddhism, shows up in classrooms wearing sunglasses: Both actor Goldie Hawn and director David Lynch fund nonprofit organizations that bring mindfulness into schools, and the 2012 documentary “Room to Breathe,” about the struggle to save a dangerous San Francisco school through mindfulness, has drawn national attention.

Mindful Schools, an Oakland-based nonprofit, is featured prominently in this film. The group has introduced 30,000 schoolchildren to this practice, defined on its website as “sustained attention and noticing our experience without reacting.”

Mindfulness teaches children how to focus their attention, manage their emotions, handle their stress and resolve conflicts through deep, purposeful breathing and reframing their thoughts in a nonjudgmental way.

It teaches empathy, as well, critical in a world of increasing intolerance, violence, bullying. “The more familiar a kid becomes with his or her own feelings, the more easily you can recognize and tolerate those feelings in someone else,” says Amy Saltzman, director for the Association for Mindfulness in Education.

When Mindful Schools partnered with the University of California at Davis to see if this practice benefited inner-city children in three Oakland elementary schools, the results left a crater imprint: 84 percent of teachers believed their students calmed more easily, and 61 percent of students said they developed better focus in class.

Researchers from the Prevention Research Center at Penn State University and Johns Hopkins joined forces with the Holistic Life Foundation, a Baltimore nonprofit that teaches yoga to at-risk youth and teachers. This September the triumvirate will begin the second half of a study in which Holistic Life and educators bring yoga into six elementary and middle schools.

“We’re taking the practice of the mat into their lives,” says Holistic Life co-founder Ali Smith.

SOCIAL EMOTIONAL LEARNING

The third front on teaching self-control — social emotional learning, or SEL — is exactly what it sounds like. The brainchild of psychologist Daniel Goleman in the 1990s, SEL presumes that the answer to America’s education woes lies not in more standardized test prep but in considering the overlooked emotional needs of kids.

SEL curricula teach children greater self-awareness and empathy, as well as the steps for handling conflict constructively and for creating positive relationships with peers, teachers and their larger communities.

Of the three approaches to teaching self-control, SEL is the one poised to make the biggest splash in mainstream public classrooms. The Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning Act of 2011 was introduced in Congress to spread the SEL gospel. The bill died in committee, but SEL inspired dedicated acolytes.

One is Rep. Tim Ryan, D-Ohio, the same Tim Ryan who wrote a book on mindfulness and spearheaded SEL programs in Ohio. Ryan and Roger Weissberg, head of the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, are lobbying the Obama administration to include SEL in its new proposals to reduce school violence.

Another acolyte is the NoVo Foundation, a New York nonprofit that is committed to funding people who strive for “sustainable,” “transformative” change. The amount that NoVo gives to CASEL varies each year; since 2008 the total has hovered near $14 million.

Responsive Classroom is one of the most widely embraced blueprints for teaching SEL at the elementary school level. It follows the premise that children learn best and grow into responsible citizens when they are taught to cultivate their emotional, as well as intellectual, needs.

A three-year longitudinal study by the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education compared children at three schools using the Responsive Classroom approach with those at three control schools.

Responsive Classroom children showed greater increases in reading and math test scores on the Connecticut Mastery Test; teachers felt more effective in teaching discipline; teachers felt that they offered more high-quality instruction; and children felt more positive about school.

Results from this study, conducted between 2001 and 2004, help explain why CASEL has partnered with citywide school systems for grades K-12 in Chicago, Cleveland, Austin and Anchorage.

On NoVo’s Web site, PS 307 teacher Martina Meijer says: “The process is transformative. The kids have grown tremendously since the beginning of the year in their ability to analyze their actions, predict consequences, and see other things they could have done.”

Faculty members say lunchrooms and hallways are calmer, teachers and students interact better, and suspensions have dropped.

“This is the future of education,” Weissberg says. “Persistence. Self-management. Problem-solving. This is what our kids need to learn.”

Andrew Reiner teaches in the Honors College at Towson College.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.