When “The Newsroom” premiered on HBO in June 2012, its opening credits, in which black and white images of Walter Cronkite, Edward R. Murrow and David Brinkley floated across the screen to soaring theme music, signaled the high-minded ambitions of its creator, Aaron Sorkin.

And if the nostalgic montage wasn’t already a dead giveaway, the events of the pilot drove home Sorkin’s purpose: After going on an inflammatory tirade about the dumbing-down of America, anchorman Will McAvoy (Jeff Daniels) returns to work at the fictional Atlantis Cable News. Urged by his executive producer (and former flame) MacKenzie McHale (Emily Mortimer), he reboots “News Night,” with the mission of “speaking truth to stupid” and moving beyond the partisan bickering of cable news in the post-9/11 era.

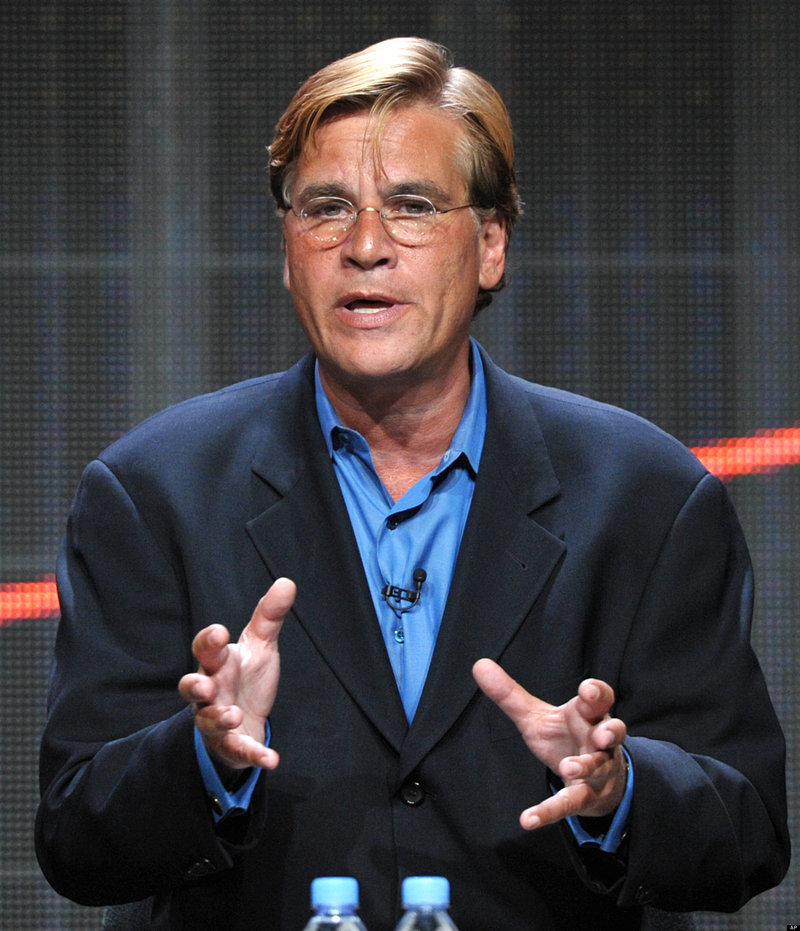

But if the Oscar-winning screenwriter of “The Social Network” had set lofty goals for his return to series television five years after the high-profile failure of “Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip,” he was soon brought back down to Earth. While “The Newsroom” earned a solid if not spectacular average of about 2.2 million viewers a week, reviews were brutal. “So naive it’s cynical,” declared the New Yorker. “Almost insufferably earnest and sanctimonious and self-flattering and smug and shrill and condescending,” ruled the Montreal Gazette.

“The Newsroom” returned in July for a second season with an understated new opening sequence that was part of a larger creative overhaul. The venerable newsmen of yesteryear were gone, replaced by beautifully lighted close-ups of anonymous hands scrolling through BlackBerries and fiddling with buttons in the control room. Instead of lamenting a bygone era of Important Journalism, “The Newsroom” was romanticizing the quotidian hustle and bustle of today’s news business.

In a reversal of fortune for the auteur behind the acclaimed “Sports Night” and “The West Wing,” the news media had piled on Season 1 with a zeal typically reserved for philandering politicians or misbehaving starlets. Hate-watching became a Sunday night ritual for members of the Fourth Estate, who slammed the show as sexist, preachy and out of touch and saw Daniels’ character, supposedly a disenchanted Republican, as a sock puppet for Sorkin’s liberal viewpoint.

“Though ‘The Newsroom’ intends to lecture its viewers on the higher virtues of capital-J journalism, Professor Sorkin soon reveals he isn’t much of an expert on the subject,” wrote Jake Tapper, then the senior White House correspondent for ABC News (now at CNN), in a scathing critique for the New Republic.

It didn’t help that Sorkin, on occasion, seemed dismissive of the very profession he was trying to portray. For instance, he chided a female reporter from Toronto’s Globe and Mail, “Listen here, Internet girl. It wouldn’t kill you to watch a film or pick up a newspaper once in a while.”

The series also invited unfavorable comparisons to the many classic films and television shows about journalism it implicitly referenced: “Broadcast News,” “His Girl Friday,” “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” “Lou Grant,” “Murphy Brown,” “Network.”

“Newsroom” hate was not monolithic among journalists, however. Dan Rather, whose image appeared in the opening credits of Season 1, wrote gushing recaps for Gawker. ” ‘The Newsroom’ is important television, the closest we’ve had to ‘must-see TV’ in recent years,” he said.

NEW STORY ARC

For the show’s sophomore outing, Sorkin enlisted 13 paid consultants, including former MSNBC and CNN President Rick Kaplan, political strategist Mark McKinnon, New Republic literary editor Leon Wieseltier, conservative pundit S.E. Cupp and MSNBC host Alex Wagner.

With their input, he made some storytelling tweaks. While “The Newsroom” still revolves around actual events from the recent past, like the 2012 Republican primary and the Occupy Wall Street movement — a device that, according to some, robs the show of suspense and allows Sorkin the benefit of hindsight — it now also includes a season-long story arc about the botched investigation of a fictional covert mission known as “Operation Genoa.”

Whether Sorkin, who declined to speak for this article, was intentionally trying to win over the press or not, reviews for the second season have improved. “The Newsroom” remains appointment viewing among portions of the chattering classes, even if disagreement about its merits persists.

John Miller, senior correspondent for CBS News, calls “The Newsroom” his favorite show and suggests his fellow reporters are being overly pedantic. “Media people are the quickest to criticize, the first ones to call something in a negative way, and the most thin-skinned when it comes to examination by anyone else. This is probably really good for them,” he says, noting that, as a former law enforcement official, he’s used to suspending disbelief by a “measure of at least 50 percent” when it comes to depictions of his profession.

Shushannah Walshe, a digital political reporter at ABC News and a consultant this season on “The Newsroom,” notes the dissonance between the largely positive reactions on her Facebook feed (comprising mostly friends and family) and the snarkier sentiments voiced on Twitter (mostly other journalists). While she readily admits the show has its implausible moments, Walshe doesn’t view this occasional lack of realism as a bad thing. “Truthfully, I think the show is aspirational,” she says.

Others take a more skeptical view. “The thing about ‘The Newsroom’ that’s funny and frustrating is it’s such an idealized version of the media that it’s unrecognizable,” says David Weigel, an MSNBC contributor and political reporter at Slate, where he and a guest journalist scrutinize each week’s episode in a feature aptly called “Trying to Tolerate ‘The Newsroom.”‘

Weigel contrasts “The Newsroom” with the decidedly more cynical HBO comedy “Veep,” which also employs veteran media consultants and, he says, does “a really good job” depicting the symbiotic relationship between the news media and Beltway politicians.

“What they present as a highbrow way of doing the news wouldn’t get past most news directors and managing editors in any local newsroom or network newsroom that I’ve worked in,” agrees Garrett Haake, a reporter at KSHB-TV in Kansas City, Mo.

While the kind of high-minded conversations depicted in “The Newsroom” do happen, according to Haake they tend to take place in social settings and not at production meetings, where the priorities are more along the lines of “OK, how can I present this in a minute and 40 and do it in a compelling way?” (And where, presumably, not everyone is able to quote Cervantes from memory.)

Haake, who followed Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign for NBC News, also has a few quibbles with a story line involving “News Night” senior producer Jim Harper (John Gallagher Jr.), who volunteers to cover the GOP primary race in New Hampshire. There, he clashes with his unusually sharp-elbowed colleagues, including a young female reporter (Grace Gummer), who when asked for help intentionally positions his camera at a bad angle. “We wanted to scoop each other, but no one would have ever done something that un-collegial,” he says.

He does appreciate the small atmospheric details the show does get right, like the omnipresent beep of the iNews system in the ACN newsroom, the turkey sandwiches doled out on the campaign trail and the curious bubble of life as an embed reporter. “You’re trapped on the bus and you’re covering events and you see a very small portion of the campaign,” Haake says. “The sense that you’re stuck on a roller-coaster that they’re controlling, they do a good job of presenting.”

LOSE THE PONTIFICATION

This is a common refrain among journalists: that “The Newsroom” is better when it dials back the pontification and focuses on the nuts and bolts of reporting, when it strives more for “All the President’s Men” than “Network.”

“If the characters would spend more time doing journalism instead of talking about journalism, it would be a far better show,” says Joseph Saltzman, director of USC Annenberg’s Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture project, who watches the show out of a sense of professional obligation but finds its didacticism tedious. “Almost every news story covered in Season 1 was accompanied by a melange of self-righteous rants, long-winded monologues and speechifying about and around the issue involved.”

One perceived flaw of Season 1 was an over-reliance on coincidence — a tendency that some say undermined the potential for drama.

In “The Newsroom” pilot, Jim is able to predict the scope of the Deepwater Horizon disaster within minutes of the first wire report, thanks to a serendipitously placed college roommate at BP and a sister at Halliburton. This was a missed narrative opportunity, says former “60 Minutes” producer Solly Granatstein.

While at the CBS news magazine, he produced an in-depth report about the BP spill, one that “took a team of seven journalists working around the clock” several weeks to put together. “I understand the need to collapse events to make fictional TV pace-y,” Granatstein says, “but perhaps ‘The Newsroom’ pilot cheated viewers of the opportunity to see the painstaking and collaborative nature of real investigative reporting.”

That’s why this season’s “Operation Genoa” arc has earned “The Newsroom” begrudging praise from even its most vocal detractors. Inspired in part by the “Operation Tailwind” scandal, CNN’s discredited report of alleged war crimes perpetrated by American forces during the Vietnam War, the fictional conceit has allowed the series to take a dive into the investigative reporting process and illustrate just how easily even seasoned journalists can be led astray.

The idea for the story line came from industry veteran Rick Kaplan, who was president of CNN when the Tailwind controversy erupted in the late ’90s. A longtime Sorkin fan, he lobbied hard to become a consultant on the series, exchanging countless emails about his experience with the writer and spending several days on set.

“I wish ‘The Newsroom’ had a hundred share. I wish everybody watched, so they would understand the Fourth Estate and maybe have a little more patience and skepticism — an honest skepticism, not a partisan skepticism,” he says. “Lifting the veil on what happens in a newsroom and doing it in an honest way helps people become better citizens.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.