GALVESTON, Texas — It sounds like something from a horror film: A beautiful, feathery-looking species of fish with venomous spines and a voracious appetite sweeps into the Gulf of Mexico, gobbling up everything in its path.

Unfortunately for the native fish and invertebrates it’s eating, this invasion isn’t unfolding on the big screen.

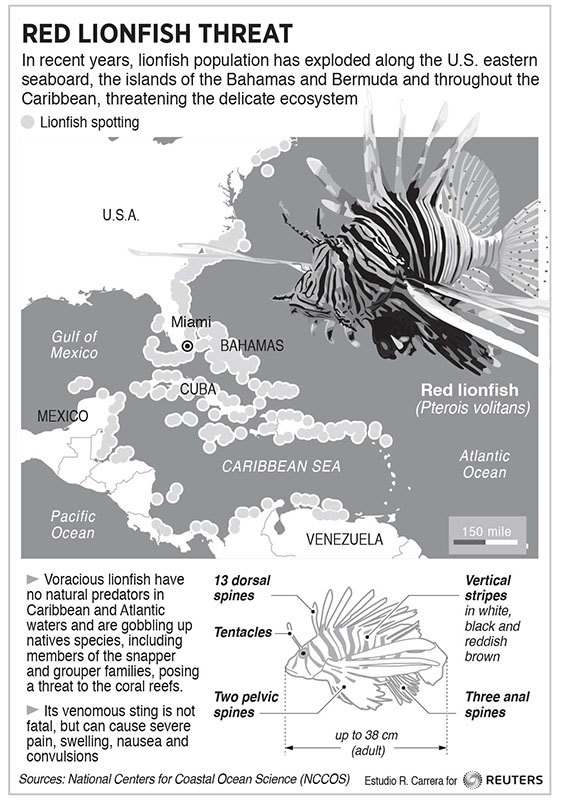

In recent months, news has been spreading of lionfish, a maroon-and-white striped native of the South Pacific that first showed up off the coast of southern Florida in 1985. Most likely, someone dumped a few out of a home fish tank. With a reproduction rate that would put rabbits to shame and no predators to slow its march, the fish swept up the Eastern seaboard and down to the Bahamas and beyond, where it is now more common than in its home waters.

“The invasive lionfish have been nearly a perfect predator,” says Martha Klitzkie, director of operations at the nonprofit Reef Environmental Education Foundation, or REEF, headquartered in Key Largo, Fla. “Because they are such an effective predator, they’re moving into new areas and, when they get settled, the population increases pretty quickly.”

The lionfish population exploded in the Florida Keys and the Bahamas between 2004 and 2010. As lionfish populations boomed, the number of native prey fish dropped. According to a 2012 study by Oregon State University, native prey fish populations along nine reefs in the Bahamas fell an average of 65 percent in just two years.

Lionfish first appeared in the western Gulf of Mexico in 2010; scientists spotted them in the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, a protected area about 100 miles off the Texas coast, in 2011. Now scuba divers spot them on coral heads nearly every time they explore a reef. So far, significant declines in native fish populations haven’t occurred here, but the future is uncertain.

‘IMPOSSIBLE BATTLE’

“It’s kind of this impossible battle,” says Michelle Johnston, a research specialist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Galveston, who manages a coral reef monitoring project at the Flower Garden Banks. “When you think how many are out there, I don’t think eradication is possible now.”

Two nearly identical species are found in the Gulf. They grow to about 18 inches and have numerous venomous spines. Their stripes are unique, like those of a zebra. They hover in the water, hanging near coral heads or underwater structures where reef fish flourish. Ambush predators, they wait for prey fish to draw near, then gulp them down in a flash.

The fish mature in a year and can spawn every four days, pumping out 2 million eggs a year. They live about 15 years.

In the South Pacific, predators and parasites keep lionfish in check. But here, nothing recognizes them as food – those feathery spines serve as do-not-touch warnings to other fish. The few groupers that have been spotted taste-testing lionfish have spit them back out, Johnston says.

In the basement of the NOAA Fisheries Science Center on the grounds of the old Fort Crockett in Galveston, Johnston sorts through a rack of glass vials. Each one contains the contents found in the stomach of a lionfish collected in the Flower Garden Banks.

She points to a fish called a bluehead wrasse in one jar. “This little guy should still be on the reef eating algae, not here in a tube,” she says. Other jars contain brown chromis, red night shrimp, cocoa damselfish and mantis shrimp, all native species found in lionfish bellies. “The amount of fish we find in their guts – it’s really alarming. They’re eating juvenile fish that should be growing up. They’re also eating fish that the native species are supposed to be eating.”

Lionfish can eat anything that fits into their mouth, even fish half their own size. They eat commercially important species, such as snapper and grouper, and the fish that those species eat, too. They’re eating so much, in fact, that scientists say some are suffering from a typically human problem – obesity. “We’re finding them with copious amount of fat – white, blubbery fat,” Johnston says.

They can adapt to almost any habitat, living anywhere from a mangrove in 1 foot of water to a reef 1,000 feet deep. They like crevices and holes but can find that on anything from a coral head to a drilling platform to a sunken ship. They can handle a wide range of salinity levels, too. Their range seems limited only by temperature – so far they don’t seem to overwinter farther north than Cape Hatteras, North Carolina – and their southern expansion extends to the northern tip of South America, although they are expected to reach the middle of Argentina in another year or two.

‘A SNOWBALL EFFECT’

“As long as they have something to eat, they’ll be there,” Johnston says.

The impact of their invasion could become widespread, scientists warn.

In the Gulf, lionfish are eating herbivores like damselfish and wrasse – “the lawnmowers of the reef,” Johnston calls them – that keep the reef clean.

“When you take the reef fish away, there’s not a lot of other things left to eat algae,” she says.

That creates a phase shift from a coral-dominated habitat to an algae-dominated one. “When you take fish away, coral gets smothered, the reef dies, and we lose larger fish. It’s a snowball effect of negativity.”

The only known way to keep lionfish populations in check, scientists say, is human removal.

That’s why lionfish “derbies,” or fishing tournaments of sorts, are popping up around the Caribbean and Gulf.

Locals are encouraged to kill and gather the fish, and in some places, including Belize, cook them up afterward.

The key is getting people to understand that lionfish are safe to eat – and tasty.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.