Maine is a place of old things known and old things not known yet and old things that can never be known. An old apple tree has no deeds. An apple tree planted in the 1860s would be lucky to merit an entry in a diary. Which is to say, where an apple tree came from can be lost to history even as the apple tree lives on.

This is the tale of a rare apple tree, dating back to the Civil War era, a story constructed from some facts, some guesswork and many names, names of Maine and names of Ireland.

For us, it started when Rowan Jacobsen, author of the recently published book “Apples of Uncommon Character,” mentioned offhandedly a specific Kavanagh apple tree in an interview last month with the Press Herald. He thought it might be the rarest apple he’d encountered, and described it as growing “basically in a parking lot near L.L. Bean in Maine.” His final word, “I think that’s the only mature Kavanagh still in existence,” was catnip to Source editor Peggy Grodinsky. She sent me to find the tree, warning me we might need to shield its exact location to protect the tree’s future and asking me to tell, as best I could, its past.

The origins of the Kavanagh variety, a yellowish-brown apple best for sauce or cooking and bearing a resemblance to the russet, are reasonably well known. Or guessed at. An Irishman named James Kavanagh came to Maine around 1790, established a shipbuilding and shipping business in the Damariscotta-Newscastle area and, at some point, planted trees from home, either from seeds or graftings he carried with him from Ireland or imported on his ships, which traveled regular routes from Wiscasset to the West Indies and on to ports like Liverpool and Cork. He shared scion wood (the part of the tree that is grafted onto rootstock) with others and, according to George Stilphen’s “The Apples of Maine,” the tree became popular enough in the region to bear his name.

But history reports the variety as being very specific to the region where he lived. What was it doing in Freeport, some 37 miles away? And how had it survived all these years, particularly the last three decades of the 20th century, when Freeport seemed to change overnight: new buildings, new businesses, houses vanishing into commerce, and always, new parking lots, generally built by people who cared most about the future, not the past.

The tree was almost disappointingly easy to find for someone on a mission – I drove into Freeport from the south, looking left and looking right into parking lots. I had barely driven a block or two when I spotted a likely candidate behind Antonia’s Pizzeria and in front of a long red building with R & D Automotive written across it.

The tree was tall and gnarled and obviously an apple tree, although it bore no fruit. I’d hoped to pluck one and take it home, slice it up and cook it in bacon fat as John Bunker, apple expert with the Maine seed and tree company Fedco, had recommended to Jacobsen.

Nonetheless, the intrigue began as soon as I pulled into the lot, eyeballing the tree and drawing the attention of the establishment’s inhabitants, including owner Rich DeGrandpre.

“Do you know the Irish lady?” DeGrandpre asked. She had a thick accent and red hair nearly as thick, the Irish works. She’d been there just last week, looking at the tree, he said. He thought maybe she was a Kavanagh, tracing her roots. I did not know her, but I wanted to, I told him.

DeGrandpre seemed entirely unsurprised to find another woman standing in front of his auto body shop asking questions about the Kavanagh. There was also a man who came by regularly to check on the tree’s health (that would be Bunker). The tree had fans. Now it had another. But none more attached than DeGrandpre, a city councilman in Freeport who has owned the property since 1976 and has marked 38 seasons with it.

He understands that the tree has achieved a kind of fame, at least in the pomological world. And his respect for the tree runs deep, even if at the beginning of his time there, he sometimes put it to work.

“If I’d known it was famous I wouldn’t have used it for auto body work all those years,” he said, chuckling. “We’d put a chain around it and use it to pull dents out of bumpers.”

His Kavanagh had a rough spring this year. It was beset by gypsy moths, who built their gossamer homes on its branches and ravaged the leaves. The leaves grew back but DeGrandpre said it had not borne fruit in 2014. He hoped it wasn’t done.

Not quite. John Bunker found a single Kavanagh apple there this year. As old as the tree is, and he thinks it is around 150 years old (apple trees can live to be 200, although not often), there is still hope for more. “I think it just took a year off,” Bunker said. “It was kind of a crappy apple year.”

Bunker had learned about the Kavanagh variety from a retired agriculture professor from the University of Maine, George Dow, who had found an old tree, much diminished, in Nobleboro and was eager to share it with Bunker. Dow knew nothing of the Freeport tree, but because of him, Bunker knew exactly what he was seeing not long after when a friend brought him an apple shaped like a cat’s head. The friend had picked it from a tree in Freeport.

“He said, ‘Have I got an apple for you,’ ” Bunker remembered. ” ‘You won’t believe it. It is so awesome.’ ” Bunker told his friend, “Yes, I would believe it. That’s a Kavanagh.”

It was John Bunker who in the 1990s took scion wood from this Kavanagh and the other that remained in Nobleboro and grafted it into the baby Kavanaghs that Fedco has sold, on and off, since 1997. John Bunker is not related to James Kavanagh, but through him, the Kavanagh line lives on.

KAVANAGH DETECTIVES

Like a character in a good noir, it seems the Irish lady is always just ahead of me, at DeGrandpre’s shop and at the Freeport Historical Society and the Maine Historical Society, where heads nod and bob at the mention of her brogue, her red hair, her interest in the Kavanaghs. It turns out her name is Fidelma McCarron and, when I found her, she told me she and her husband, Edward, a history professor from Stonehill College, first met in the town of Inistioge in County Kilkenny, just a handful of miles from the Nore Valley farm where James Kavanagh grew up.

Edward McCarron has researched early Irish immigrants in Maine, including writing an extensive history of Kavanagh and his business partner, Matthew Cottrill, “The World of Kavanagh and Cottrill: a portrait of Irish emigration, entrepreneurship, and ethnic diversity in mid-Maine, 1760-1820.” The couple read about the Kavanagh tree of Freeport and were as tempted by the apple story as we were. “Just the fact that the tree survived in a parking lot,” Fidelma McCarron said. “Why?”

From McCarron’s history and several others at the Maine Historical Society, a picture emerges of Kavanagh as a go-getter who was ultimately crushed by his own business. He left Ireland for Boston either in 1780 or 1784, depending on which history you believe, and in Boston partnered with another young Irish immigrant, Cottrill. They were both Catholics and ambitious, although Kavanagh seems to have been the driving force behind the business they started in Newcastle around 1790. In the spring of 1795 they bought two sawmills and the 567-acre Lithgow Farm on the Damariscotta River. By 1799 they had paid off the mortgage, built a bridge over the river and become successful boat builders.

In between overseeing the businesses, they built themselves mansions, planted orchards and gave their growing community its first Catholic Church (over 300 Irish immigrants settled in Lincoln County between 1760 and 1820).

They brought relatives in to help with the booming business, including Cottrill’s sister Catherine and her husband, who arrived in 1804 (“She could have brought some trees from the valley then,” Fidelma McCarron theorizes). But the War of 1812 nearly ruined them. Cottrill survived the time of embargo and strife better than Kavanagh, who is said to have later lost his taste for the sea entirely after his son John disappeared on a voyage to the East Indies in 1824. (Another son, Edward Kavanagh, became a politician and served, briefly, as Maine’s first Catholic governor.)

Kavanagh and Cottrill died within weeks of each other in 1828. Bunker believes that Mainers stopped planting the Kavanaghs a few decades later.

Around the time Kavanagh’s influence in orchard plantings was dying out, a Portland grocer named Daniel Cobb Reed was relocating to Freeport, just across the street from his wife’s family. Make that both of his wives’ family. He’d first married Jane E. Griffin, the seventh child of Henry Griffin and Patience Sherman Griffin. After Jane died in 1848, he married her sister, named Patience for her mother.

THIS LAND WAS REED’S LAND

When Kavanagh was settling in the Damariscotta region, the Griffin family was already well established in what is now Freeport. There were many Griffins around the area, but the relevant Griffins owned property on what has been variously known as the Old County Road or State Road and even Federal Road. We know it as Route 1. Property records for the house that still stands on the old Griffin homestead – across the street from R&D Automotive and what I’d come to think of as the Kavanagh tree – date it to 1760, although documents at the Freeport Historical Society describe a fire there in 1817 that suggests the house was rebuilt.

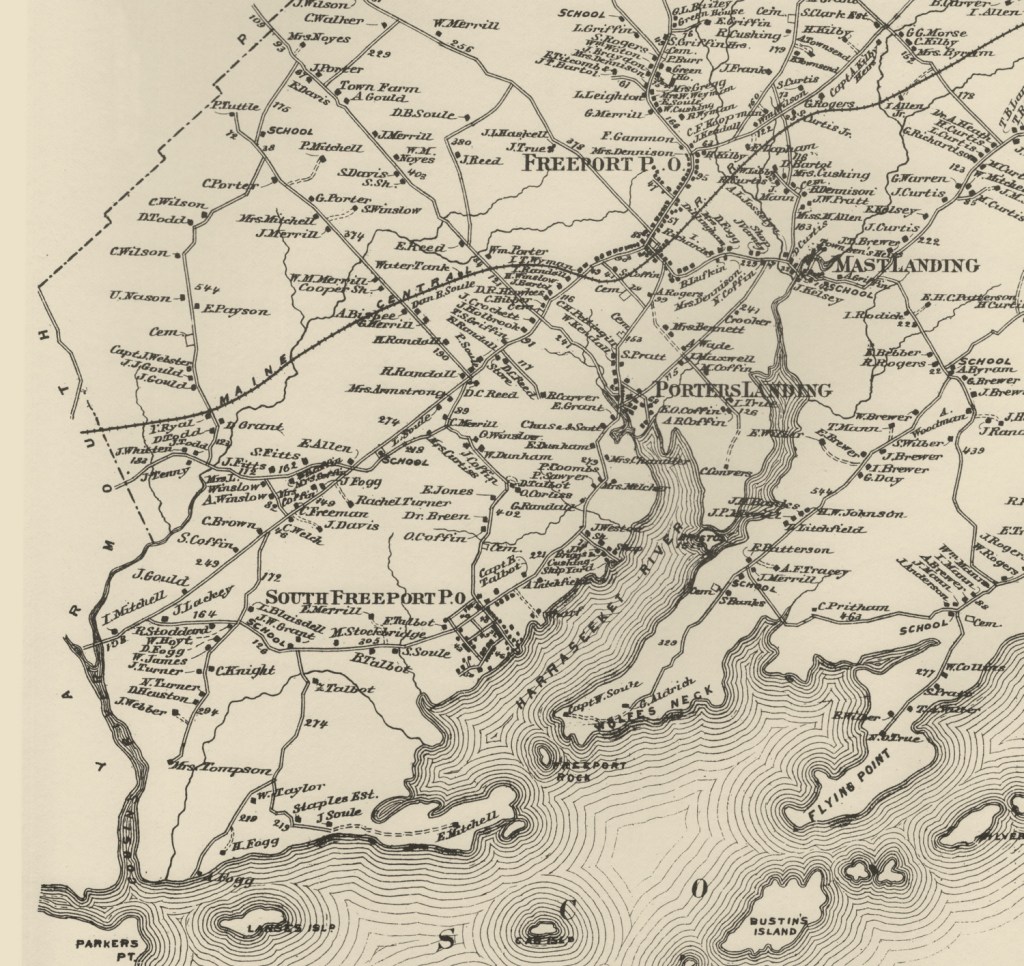

Daniel Reed’s father-in-law, Henry Griffin, died in 1836. His mother-in-law, Patience Sherman Griffin, had been living with her daughter Jane and Reed in Portland at the time of her death in 1839. A deed from 1852 shows Daniel Reed and his new wife, Patience Griffin, granting a piece of Henry Griffin’s former holdings to one of Patience’s brothers. The land went back and forth between siblings and cousins, but what we do know from Freeport maps dating to 1857 is that Daniel Reed, or DC Reed, was living in Freeport with his wife by then, running a store on what is now Route 1, just a stone’s throw from where the tree stands. In 1865 he purchased a tract of 25 acres from another family, presumably expanding his holdings.

The Griffins were farmers. The Reeds had more diverse careers. Daniel Reed had spent part of his youth in Durham, where the Reed family farmed, but they had also been involved in shipping and fishing, with Daniel described, pre-grocery days, as a mariner. Fidelma McCarron, the “Irish lady” who continued to cross my path as we both researched, found this fact in the Portland city directories. Reed reinvented himself later as an attorney.

Working from John Bunker’s hunch about when the Kavanagh apple went out of vogue and his best guess about the tree’s age, Daniel Cobb Reed seemed the likeliest candidate to have planted Rich DeGrandpre’s tree. There was a George Reid who worked with Kavanagh and Cottrill, and historians say the different spelling doesn’t mean Reed and Reid weren’t related. Maybe he gave the tree to Daniel Reed. Whatever the case, the apple expert is certain it did not come from a seed. It was no accident.

“That tree was grafted,” Bunker said. “It had to come from Nobleboro.”

Bunker suggests it perhaps came by sea, traveling on a Kavanagh and Cottrill ship making its way down the coast. It turns out Jacobsen wasn’t entirely right about the Freeport tree being the only one of its kind; Bunker knows of another mature Kavanagh still standing in Arrowsic and one in Blue Hill, again, close to the coast. The tree could have come by land, from someone from Nobleboro or nearby (Patience Reed’s nephew Charles married a Whitefield girl in 1873), maybe someone who boasted of the fine sauce to be made from a Kavanagh and brought scion wood to Freeport for a landowner. “Probably somebody who had some money,” Bunker said. Like, say, a man who owned a store.

Bunker is certain the tree would not have been alone. Maybe it stood with 10 other trees, Bunker said, although “my guess is if it was in Freeport, it was a considerably larger orchard.”

Today you can walk DeGrandpre’s property and find crab apple and wild cherry tucked in to the tangles of trees near his shop. But the Kavanagh stands alone. Bunker likes the tree. But he doesn’t need answers about its history in order to care about it; he accepts how little we can actually know.

“People are going to speculate about us in a few hundred years,” Bunker said. He’s right that they’ll probably get a fair amount wrong, even with Facebook and Twitter recording every move we care to share. “Maybe we get 10 percent of this story right.”

BUSHELS OF APPLES

A reporter can get obsessed. It’s one of the pleasures of the job, actually. But editors have to make sure the story gets in the paper as planned. I was attempting to make the case that I needed just a few more hours with the story to drive to Augusta and spend some time with dusty old agricultural census records when Fidelma McCarron wrote to say she’d been through the census and found records of Daniel’s orchard dating to 1880: two hundred fruit bearing trees, yielding 75 bushels of apples worth $45. He had 25 acres of hay, an acre of potatoes, oats and beans, along with hens and a milk cow. He appeared to have a hired man on hand to help, maybe with the store or the farming, a man whose surname turned up later in the will of the next person to own the land after Daniel Reed, a nephew by marriage named John T. Griffin, who went by Tom.

Freeport was undergoing radical change in the second half of the 19th century. The train had come through in 1849. By 1860, the population was 2,791. By 1886, a man of just 33, E. B. Mallet, had built himself a little empire there: a shoe factory, a saw mill, a grist mill, a coal yard and a department store with 12 clerks. For Reed, down the road and out of the center of the village proper, maybe the competition was too much. Maybe he longed for a life in the city. In any event, he died in Portland in 1892, three years after Tom Griffin took over the land. Who knows if Daniel Reed told his nephew to look out for that particular tree, the one that bore the yellow apples shaped like the head of a cat? But the tree lived on under Tom Griffin’s watch, just across the county road from his own house, the one people called “the house on the hill” or “the Griffin homestead.”

Self-described in the census as a farmer, Tom was one of 13 children born to Patience’s older brother Thomas Sherman Griffin. He was active in the farming community, serving as the first overseerer of the Harraseeket Grange in the 1870s. And he was enough of a patriarch in the Griffin clan to take in his sister Sarah Jane and raise her baby Winifred Mae Beck as if she were his own, according to Freeport town history gathered by Col. Thurlow R. Dunning, who uncovered reams of local history while pursuing his own genealogy. Sarah Jane’s husband, Samuel, an engineer, was out west in Colorado, taking a crack at mining.

Winifred Beck graduated from Freeport High School in 1897 and went to college at the Farmington Normal School. She later moved to Boston, where she worked as a secretary at an engineering firm, lived on Beacon Hill and took care of her mother until her death in 1910. She visited often in the summers and a photo from 1906 shows her in a tight group of family members on the porch of “the house on the hill,” Tom standing in the middle. Just a year before, George Farrington Dow, who would grow up to teach agriculture and become fascinated with the Kavanagh apple, had been born in South Portland.

While she was visiting from Boston, presumably Beck noticed how that other local family business, L.L. Bean, founded in 1912, seemed to be growing. When she wasn’t visiting, she was sending money home to help the Griffins of Freeport. She’d become a woman of some means, acquiring 93 shares of American Telephone & Telegraph Co. stock and 165 shares of General Motors Corporation common stock, according to legal records.

Her uncle Tom Griffin continued to farm while Freeport developed around him. A developer with big, ultimately unrealistic dreams about the power of the trolley era, built Casco Castle and Amusement Park in South Freeport in 1903, along the trolley line. Maybe Tom and his wife paid the 5 cents to ride it down to see the view of the harbor. Maybe they climbed the castle’s stone tower, looking out on Pound of Tea island at the mouth of the Harraseeket River. Maybe Tom Griffin liked to visit with the monkeys in the small zoo. Maybe he scoffed at the idea of a resort so close to his family farm. But Casco Castle was gone by September 1914, burned to the ground just as the summer guests were leaving.

Only the stone tower still stands, on private land. Like that Kavanagh, it stands as a testament to a very different Freeport.

BROTHERLY ADMONITIONS

When Tom Griffin died in 1934, he left the homestead to his sisters, hoping it would stay intact. His will contained some brotherly advice: “I suggest to my said sisters that said homestead place as it is now constituted in [sic] much more valuable as it now is than it would be if some parts or portions of the same were sold and conveyed separate from the rest, and I therefore would recommend that if at any time hereafter said place is to be sold, it be sold as a whole, and not in separate pieces.”

To loyal Winifred Beck, raised as his daughter, he left the land across the street, where the store had been. Almost immediately she deeded her land to one of Tom’s sisters, Helen T. Griffin, and from the 1930s through the 1970s, against Tom Griffin’s advice, the properties were further divided, chopped up in smaller and smaller pieces, some with liens on them and some changing hands so rapidly there would hardly have been time for any one owner to harvest apples.

Freeport was still a shoe-making hub, and still growing, with Bean’s becoming more of a presence in the ’50s. “The shoe factories were still very much an economic force in the 1950s and into the 1960s,” said Maine State Historian Earle Shettleworth, who grew up in Portland but spent time in Freeport in that era. Shettleworth’s father bought the old Clark block after a June 26, 1946 fire destroyed a hotel and stores in it.

Maybe Beck was visiting, staying at the old homestead with cousins as she did when she came home in the summers. Maybe she saw the flames, smelled the smoke. Maybe she shopped in the new store Shettleworth’s father opened within months of the fire. Or across the street, at Bean’s.

The apple tree lived on. It would have set its fruit the month of the fire. Shettleworth never knew anything of the sturdy tree down the street from his father’s business, but he remembered what Freeport looked like then. “It was all these nice homes, with landscaping,” Shettleworth said. “I can even remember that there were still elm trees along Main Street,” he said.

COMING HOME

In 1959, Winifred Beck returned home to live in Freeport at the house on the hill for good. Her cousin had died and the homestead sold to a Freeport undertaker named Russell Jeannotte, who rented Winifred the old Griffin homestead for $150 a month. Two years later, at the age of 82, she died, leaving most of her estate to Jeannotte. There were questions about how sound her mind was at that point, and a judge set aside the will, denying Jeannotte the money. He sold the old Griffin homestead and its eight acres in 1973 to the people that own it today. The plain little house at the corner of Varney and Route 1, where once Reed’s store had been, had passed into the Bartoll family in the late ’30s and remained in their hands until the early 1960s.

The ’60s, time of change across America, brought about the biggest change to the old Reed land, by that time described as Lot No. 56 in property records.

In 1962, a couple named Clyde Damone and his wife, Barbara, bought the house. Longtime Freeport resident Ed Bonney remembers Damone as a career military man and Barbara as a friend to his own wife, Betty. Bonney knows of DeGrandpre’s apple tree now, but has no recollection of the Damones picking its apples. Around 1968, the marriage unraveled, the Damones divorced that October and Barbara was awarded the house and the four acres it stood on. She sold the land the next year to James Lumsden, a social studies teacher from Freeport High School.

Jimmy opened a clam shack, the size of a one-car garage, on the land. He was a well-known figure around town, a man who had parlayed his lobsterbake business into something big, preparing bakes for politicians, from Ed Muskie to Ted Kennedy and even Jimmy Carter at the White House. He’s gone now, but the business evolved into Maine Shore Lobster Bake, run today by Lumsden’s niece Sonya (she doesn’t remember an orchard on that land). Some of his property on the other side of Varney Road was used for new homes.

“Jimmy Lumsden developed that,” Rich DeGrandpre said, gesturing toward a housing complex across Varney Road. The two men, related by marriage, were building businesses at the same time, all on land that had once belonged to the Reeds and Griffins.

It was a funny combination of residential and commercial use. On the one hand, there was DeGrandpre taking care of cars, and people getting their cars washed at a new carwash nearby (now home to Lincoln Canoe & Kayak). A man named John Lewis turned the old house where the Damones had lived into a popular restaurant called the Blue Onion. On the other hand, the old homestead stayed a home, and new families raised children, fought over homework and perhaps planted gardens in the boxy little development Lumsden had built.

The patch of grass around the tree dwindled until it lived in something not much wider than a median. Yet the tree stood, throwing shade on DeGrandpre’s parking lot and dropping apples every fall. Sometimes on customer’s cars. “I don’t know what it is,” he said. “People always seem to want to park under that tree.”

Within the same time frame that DeGrandpre was growing fond of his apple tree, George Dow had retired to Nobleboro. His long career as a teacher had left him with a taste for history; he organized the Nobleboro Historical Society in 1978 and began compiling information about the area’s families, buildings and as it turns out, its apples, and writing about them for the Lincoln County News. His book, “Nobleboro, Maine – A History,” co-authored with Robert E. Dunbar, was published in 1988. It mentions the Kavanagh apple, which in just a few short years, Dow would introduce to Bunker. Dow too, in albeit a circuitous way, can be connected to the Freeport Kavanagh. Without him, Bunker might never have known to nurture the variety these two last decades.

In 2006, the old Blue Onion building was demolished to make way for Antonia’s Pizzeria, removing the last building standing on that side of the street with direct ties to the Griffins. The tree that they had borne fruit for them remained though, watched over by a man with an automotive repair shop, visited regularly by Maine’s foremost apple expert and held up by a food writer as the rarest of the rare. Since 1997, Fedco has sold about 150 Kavanaghs, many of them offspring of this tree. Two ended up in Wiscasset, planted on the property line of a man named Edward Kavanagh, a retiree from the Boston area who believes himself to be no relation to the original James Kavanagh. This Edward Kavanagh didn’t plant the trees – his neighbor did – but he has been pleased to see a tree that bears his name growing there and to be given an apple from it. It means something, although it is hard to define what. It is not as simple as taste. (“If it wasn’t a Kavanagh apple,” he said, “I’m not sure I’d try it again.”) It’s more about the links between another man named Kavanagh and how the power of his taste in apples still resonates and motivates today. “It is strange how all the interconnecting fibers pull you in,” Kavanagh said. “And you don’t even realize it.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.