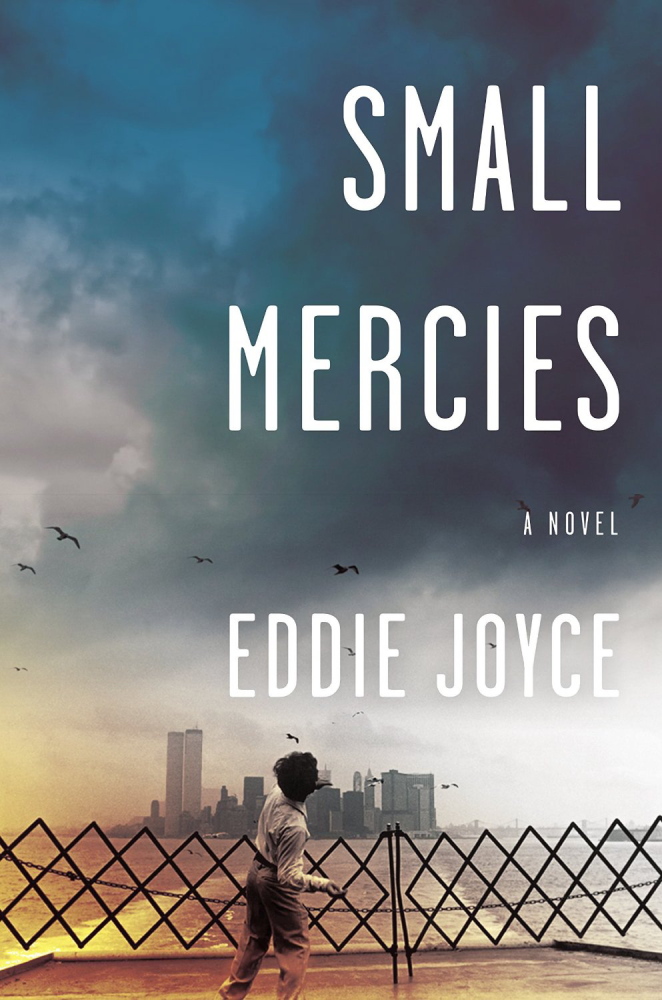

I could not help but think of the line from Joan Didion’s memoir, “A Year of Magical Thinking,” in reading Eddie Joyce’s debut novel, “Small Mercies.” Didion writes that “Grief turns out to be a place none of us know until we reach it.” Joyce more than makes this notion his own in his story of the Amendola family of Staten Island. His story is of their struggle to navigate their lives in the long shadow of the attacks on the World Trade Center on 9/11.

Tragedies aren’t measured just by what comes after. Joyce adeptly weaves threads of what came before and how those threads flay and entangle the forever-altered lives of one family who lost a son-brother-husband-father, someone who rushed into a burning tower as a New York City fireman and emerged only as a haunting absence.

Bobby Amendola, who died that day, leaves Gail Amendola, a middle-aged mother and schoolteacher who “wakes with a pierced heart, same as every day.” This greets the reader in the opening line about a morning nine years on in the wake of the tragedy. There is also Michael, her husband, a retired firefighter, who, when he looks in the mirror, sees the face of his father. His father had always wanted Michael to follow him into business as a butcher. The face that stares back always seems to say, “If you’d taken the shop, maybe Bobby would still be alive.”

There is also Peter, the eldest son and golden boy who flees Staten Island, what he deems “the servants’ quarters of the city.” The day he achieves his dream to make partner at a tony Manhattan law firm, he breaks down sobbing because “Bobby was still dead.”

Franky is the middle son, lost and angry, “a drunken ruined memorial to his dead brother.” Franky harbors the wish that it had been him and not his brother – while fearing at the same time that everyone else in the family wishes the same.

And finally, there is Tina, Bobby’s widow, mother of two young children, who fought with her husband the night before 9/11, was angry when he went off to work, and who, “when he died, was still mad at him.” When Tina finally tells Gail, her mother-in-law, that she’s met someone – this nearly 10 years after Bobby’s death, Gail wishes her well, but can’t help but think, “It’s too soon … an insufficient amount of time has passed.”

Joyce gives us a world limned in unadorned prose, but one painted in rich detail. There are dazzling, revelatory lines throughout. Such as when Gail checks herself in the mirror after rising: “Not for vanity, not anymore, but for its older sister: dignity.” Or when one of her young sons comes home after a night with a local college girl several castes higher than the Amendola clan, “it was an odd thing to be happy that your son had maybe screwed above his station. But she was happy. Proud, too.”

The Amendola family is Italian-Irish, a mix of traditions and histories, grounded in Michael, who grew up on Staten Island, and Gail, the Irish girl he brought home to “the Rock,” and who now, he knows, would never tolerate any attempt to unlatch her precious hold on the place. It is solidly working class, like the preponderance of the community that surrounds it, a community fiercely – even defiantly – proud of its blue collar heritage, peevishly lamenting the steady gentrification that came with completion of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge.

“Small Mercies” is the story of a family and of a tragedy, but it is also a story about “place” in the best tradition of American literature.

The title of the book comes from a common verbal tick that several characters utter in response to fresh tragedies, always seeking to seize hold of small mercies that might mitigate the loss. There is a moving example where Gail and Tina are together at a kitchen table and Tina is telling Gail stories about Bobby, stories that reveal a side that Gail had never allowed herself to acknowledge, stories of Bobby’s anger, his occasional selfishness.

“Just when you think the sadness can grow no larger, your son’s widow tell you that – no, confesses that to you – and the grief pushes through a door you didn’t know was there to occupy a space you didn’t know existed.… It hits you differently each day. You owe it respect in some ways. You have to mourn everything: the flaws as well as the virtues, the bad moments as well as the good. You have to turn over every rock and embrace the individual sadness you find underneath. The Bobby stories did that.

“Together, Tina and Gail gave grief its due.”

Eddie Joyce abundantly gives this to his readers in “Small Mercies.” Consequently, it is likely that readers will likewise find themselves also giving grief its due for days following the final turning of the page.

Frank O Smith is a Maine writer whose novel, “Dream Singer,” was named a Notable Book of the Year in Literary Fiction by Shelf Unbound, the international, indie book review magazine. Smith can be reached via his website:

frankosmithstories.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.