City crews began knocking down the raised center median on Middle and Spring streets this week in the first step of a plan to undo some of the damage caused by a 1970s-era urban-renewal project.

That project was stopped by historic preservationists four decades ago, but its legacy remains – a divided highway less than a half-mile long dropped into the middle of downtown Portland.

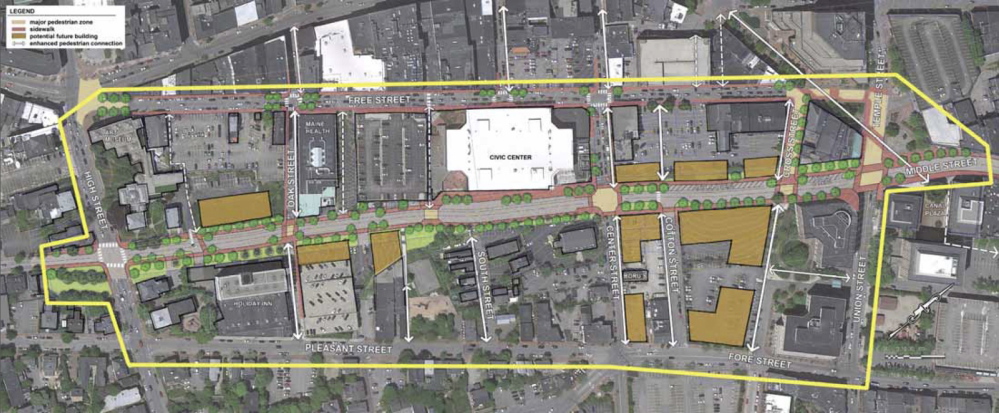

Now city planners want Spring Street to look less like a highway and more like a typical downtown street. The goal is to “re-knit together much of the urban fabric that was lost,” said Bruce Hyman, transportation program manager for Portland.

When the project is complete, the street will be narrower at the intersections, making it easier for pedestrians to cross. One turning lane will be eliminated at three intersections – High Street, Center Street and Temple/Union streets – and the north side of Spring Street will be reduced to one lane for the short distance between Center Street and the Spring Street garage. Also, a bicycle lane will be added to the north side of the street.

Eventually, city officials hope the project will spur owners of the ample undeveloped adjacent land to erect new buildings. Long-range city plans call for selling portions of the 90-foot-wide public right-of-way for development.

The project’s $2 million cost, which will be split between the city and state, includes repaving Spring, Temple and Middle streets. Officials hope the project will be finished by the end of the year.

“This is the type of investment that can really help spark people’s desires to invest in their properties,” said City Councilor David Marshall, who represents the West End.

PEDESTRIANS, BUSINESSES APPROVE

Mark Bessire, director of the Portland Museum of Art, called the barrier’s removal a “great step, and a symbol of how considerate planning and oversight” can improve the area. The museum owns a parking lot and house on Spring Street.

There was universal support for the project among pedestrians and business owners interviewed on Tuesday.

“That’s cool. I don’t see a lot of downsizing going on in cities,” said Baxter Key, 24, who operates a lobster roll stand at the corner of Middle and Temple streets.

Key said his customers support the project, except for some teenage boys who use the concrete medians as a skateboard park. He said the boys looked exasperated as heavy equipment tore down the medians.

Spring Street used to look like other two-lane downtown streets. Then in 1967 the city hired Victor Gruen, a planning consultant who pioneered the design of shopping malls in the United States. Gruen wanted to create a ring of highways around the city’s business district.

Ring-road systems were seen as a way to help downtowns survive as the population – and commercial activity – moved to the suburbs.

High and State streets were converted to one-way arterials. Also around this time, about 130 buildings were razed to make room for construction of Franklin Arterial, which was initially promoted as a six-lane “crosstown expressway.” Two of the lanes were never built.

‘HUMANIZING THE SPACE’

The Spring Street Arterial was supposed to be part of that ring, connecting the Franklin Arterial with State Street via Middle Street. Work began in the early 1970s. A section starting at Temple Street was cleared for the arterial. Victorian commercial buildings and a row of 19th-century houses were demolished.

“By the time they bulldozed their way down to the Old Port, there was a lot of opposition to what they were doing,” Marshall said.

Historic preservationists stopped additional demolition, putting an end to plans for the ring road.

Markos Miller, a Munjoy Hill resident who has advocated for similar changes to Franklin Arterial, said planners have learned they can still move high volumes of traffic on ordinary city streets, and that highway infrastructure, like center medians, is unnecessary.

“We can change the nature of the street and the place around the street – not by restricting vehicle traffic but by humanizing the space,” he said. “We can move cars better and people better on regular city streets.”

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.