Maine’s vaccination opt-out rate for kindergarten-age children in 2014-15 remained higher than the national average, even though the number of parents who decided not to immunize their children has declined.

Maine has the eighth-highest opt-out rate among the 45 states represented in the CDC data – down from fifth highest in 2013-14 – and was one of only 11 states with opt-out rates at or above 4 percent, according to school survey data released Friday by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During the 2014-15 school year, an estimated 4.4 percent of children enrolled in kindergarten across the state did not receive vaccinations for contagious diseases such as measles or whooping cough because parents chose not to for medical, religious and philosophical reasons, according to the CDC data. That’s down from an opt-out rate of 5.5 percent during the 2013-14 school year. The opt-out rate for just religious and philosophical reasons was 3.9 percent in 2014-2015 and 5.2 percent in 2013-14.

Parents of a total of 599 kindergarten students claimed medical, religious or philosophical exemptions in Maine last year, down from 796 during the 2013-14 school year.

The national median exemption rate for all reasons was 1.7 percent in 2014-15.

Maine saw the second-largest decline nationally after Kansas, which saw a drop of 1.2 percent.

Medical professionals warn that “herd immunity,” the protection that occurs when almost everyone is immunized, begins to break down when less than 95 percent of the population is vaccinated.

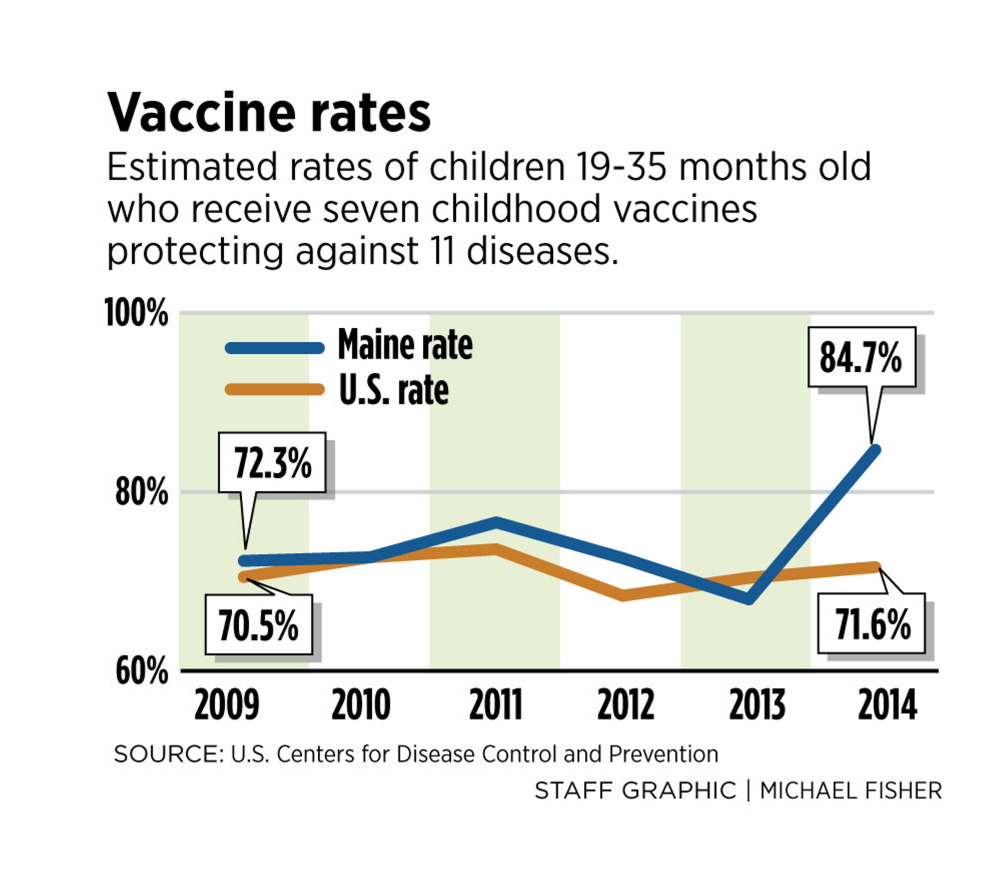

Meanwhile, Maine also reported a significant increase in the vaccination rate for children between the ages of 19 months and 35 months, rising from 68 percent to 84.7 percent between 2013 and 2014. The increase was so large that Maine jumped from the middle of the pack to the national leader last year. The national average for immunizations of 19- to 35-month-olds was 71.6 percent in 2014.

State health officials and health industry experts cheered the positive news on both fronts. While they cautioned against reading too much into one year’s numbers, health observers said Maine’s recent focus on improving the vaccination rate appears to be bearing fruit.

“Though there might be some bouncing around of the rates (between years), it does appear to be a statistically significant increase in the vaccination rate,” said Dr. Dora Anne Mills, former director of the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention and current vice president for clinical affairs at the University of New England. “And I believe that if those efforts continue, they will help to sustain these rates.”

In recent years, Maine has waged a multipronged approach to improving the vaccination rate, focused on making it easier for doctors to obtain and administer vaccines while educating the general public about the importance of immunizations.

Tonya Philbrick, director of the Maine Immunization Program at the Department of Health and Human Services, said the state has seen some “extraordinary partnerships” between the state, hospitals, health collaboratives such as Maine Quality Counts, and doctors at the local level.

“But I really think parents are starting to make informed decisions based on scientific or medical information from their providers,” Philbrick said.

RISING OPT-OUT RATES

Immunization rates have always been a concern for health officials, but were thrust into the spotlight after several high-profile outbreaks of diseases that are typically controlled by vaccines. In California, more than 100 people were infected during a measles outbreak traced to Disneyland last year. Cases of whooping cough – also known as pertussis – have spiked around the country, including in Maine, where 737 cases were reported in 2012 – the highest in more than 50 years.

Maine is one of about 20 states that allows parents to exempt their school-age children from required vaccinations for religious or philosophical reasons. Before 2014, Maine’s opt-out rates rose as more parents used the philosophic exemption, driven in part by concerns about potential links between vaccinations and disorders such as autism. While all vaccines have potential side effects, substantial scientific research has debunked the alleged autism connection and shown that vaccines are safe, according to the federal CDC.

Maine’s opt-out law currently only requires parents to sign a form citing a medical, religious or philosophical exemption. The opt-out rate rose from 2.7 percent during the 2003-04 school year to more than 5 percent during the 2013-14 school year, a surge driven entirely by religious or philosophical objections.

With some schools recording opt-out rates exceeding 20 percent – well above the herd immunity threshold – health groups fought unsuccessfully to eliminate or tighten the exemption during the legislative session that ended in July. A bill to require parents to get a signature from a medical professional before opting out of vaccinations passed the Legislature, but was vetoed by Republican Gov. Paul LePage, who argued the legislation violated parental rights.

Maine’s opt-out policy puts doctors on the front line in answering questions from concerned parents.

“I have conversations with parents,” said Dr. Lisa Ryan, a pediatrician at Bridgton Pediatrics who currently serves as president of the Maine Medical Association, a trade group involved in policy discussions in Augusta. “I talk to parents about the risks and benefits, and I think it is important, if people do opt out, that they understand the risk … and we talk to them at every visit we can about the importance of immunizations.”

Ryan estimated that 3 percent to 4 percent of her families opt out of some vaccines but very few choose not to vaccinate at all. She was encouraged by the latest CDC figures and credited the collaborative efforts among state programs and Maine’s healthcare providers to improve the vaccination rates. Media coverage of outbreaks also has had an impact.

“After the measles outbreak in California, I had a family who are reluctant vaccinators come in and say, ‘I want to get the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) right now,'” Ryan said.

South Portland resident Erin Shaw-Nkurunziza said Friday that she was concerned about the side effects of vaccinations when she was pregnant with her first child. So she did some initial research and then talked with her doctor extensively after her daughter, Josie, was born about 18 months ago. Shaw-Nkurunziza said she is always given a pamphlet after each shot with information about the immunization and possible side effects, and they carefully monitor her daughter for signs of fever or other issues outlined in the pamphlet.

“After talking with my doctor, I felt very confident that we are doing the right thing for Josie by getting all of the immunizations,” she said Friday, several hours after her daughter received her latest vaccination.

HEALTH OFFICIALS OPTIMISTIC

Health experts caution that it is too early to celebrate Maine’s improving vaccination rate and falling opt-out rate based on a single year of data. The vaccination rate for 19- to 35-month-old children, for instance, is based on telephone surveys of parents and has varying levels of survey confidence depending on the size of the respondent pool.

But observers are optimistic that the rates are headed in the right direction.

Cassandra Cote Grantham, director of childhood health and community health improvement at MaineHealth, the nonprofit that includes Maine Medical Center and Southern Maine Health Care, said health practitioners cannot “rest on our laurels” and must check the immunization status of every child that comes through the office. At the same time, they must actively educate parents while continuing the industry collaboration.

“This is going to be a long road and it is going to take continuous vigilance,” Grantham said. “This is one point in time. I think we need to wait and see over the next couple of years if the programs we have put in place are still (bearing fruit).”

Dr. Dieter Kreckel, a family physician with Swift River Family Medicine in Rumford, said he does not see many clients who opt out of vaccinations for their children. Kreckel said he talks with parents who express concerns about vaccines, discussing the potential side effects but also the benefits, both to the child and to the wider community. Kreckel said he also sends them home with literature, although the decision is ultimately up to the parent.

“The message is everybody needs to get their vaccinations,” Kreckel said. “It is important that people pay attention. You can’t just rely on the person next to you for immunity.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.