Whenever Anthony Amore gives a speech, he asks for a show of hands from the audience. “How many of you have had a piece of valuable art stolen from your home?”

Nobody raises a hand.

And yet, the public is fascinated by the high-rolling world of art thievery and forgery thanks to Hollywood, which often portrays art crimes as sophisticated plots executed by savvy, daring criminals. It’s sometimes like that in real life, but not often, Amore said. Usually, the crimes are far less sophisticated, but the stories behind the crimes and the paintings that are stolen or forged are endlessly fascinating, he said.

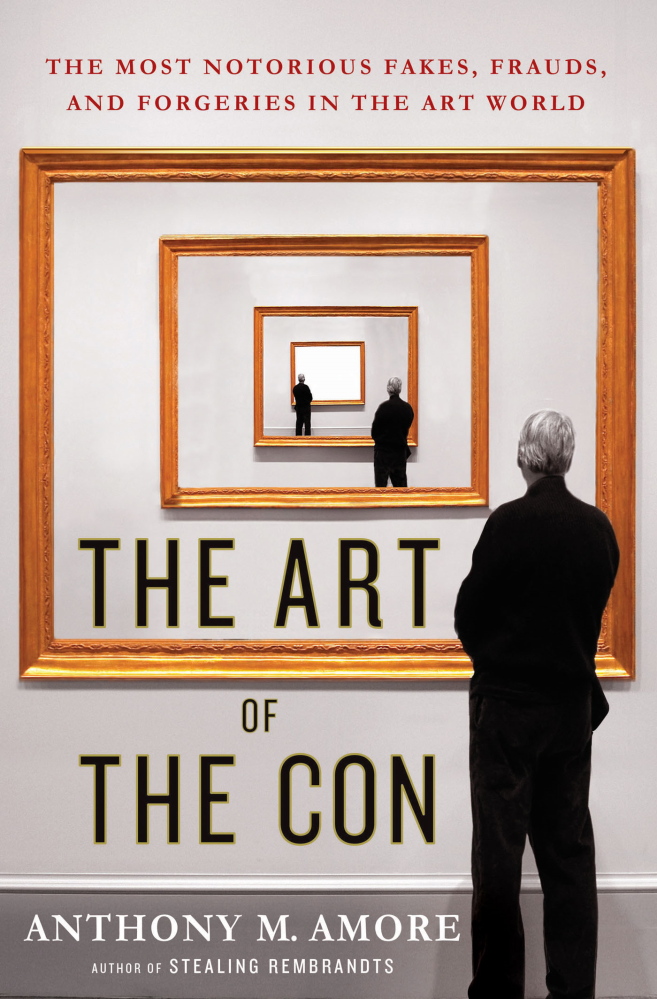

Amore, head of security and chief investigator at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, has just written a book about the history of the most notorious and lesser-known art crimes, as well his own experiences. “The Art of the Con: The Most Notorious Fakes, Frauds and Forgeries in the Art World” includes the stories of Los Angeles art dealer Tatiana Khan, who convinced a painter to make a fake Picasso, which Kahn then promoted and sold as the original, as well as dealer Kristine Eubanks, who passed off prints as authentic on eBay.

Amore has been security chief at the Gardner for 10 years. He began his job there long after the infamous 1990 theft of 13 paintings worth $500 million, including paintings by Degas, Rembrandt and Vermeer. He describes his job like this: “What I do is protect the collection that is here at the museum. That is job No. 1, to make sure our collection and our people are secure. The other part of my job is finding the paintings.”

The search continues, he said. It’s ongoing and continuous, and endlessly frustrating despite the leads and headway that he and other investigators are making. “I kind of describe it as looking for 13 needles in a haystack. Every day is spent trying to make the haystack smaller. The job isn’t just trying to find new leads, but eliminating possibilities. Every single day we make progress in that respect,” he said. “I maintain confidence we will recover them. The day I stop believing we will get them back is the day I turn the job over to someone else.”

Art crimes have been in the news in Maine lately, as well. Along with persistent rumors that the perpetrators of the Gardner heist stored or moved the paintings through Maine, the FBI and Portland police are searching for two paintings by N.C. Wyeth stolen two years ago from Portland businessman Joe Soley. In July, a New Hampshire man was convicted of illegally transporting four other N.C. Wyeth paintings stolen from Soley at the same time.

Most of Amore’s book deals with fakes and frauds, which is more common than people realize, he said. Some experts say that 40 percent of the art sold is fraudulent, though Amore finds that statistic “enormously high.” Regardless, art scams are so common, he said, that experts are growing leery of authenticating paintings. It’s getting worse with the advent of technology, because so much art is sold at auction online and via e-commerce. Buyers trust the dealers they’re buying from, in part because they want to believe that what they are buying is real and valuable. It may not be, Amore said.

Oftentimes, that prized painting is a fake, forged by an expert. In the vast majority of cases, forgeries are never solved, he said. Fraud involving famous paintings, or masterpieces, has a much higher probability of being solved, because those paintings are recognizable. But art theft in general has a low rate of resolution, which is one reason why it’s so common, he said.

Coincidentally, the Portland Museum of Art is showing a movie this weekend about German art forger Wolfgang Beltracchi, “The Art of Forgery.” (The final showing is at 2 p.m. Sunday). Beltracchi has a recurring role in Amore’s book.

Amore said he receives inquiries regularly from people asking for help authenticating paintings they’re interested in buying. His advice is always the same: Do your research.

Just as a used-car buyer will investigate a vehicle’s history, so too should art buyers investigate the history of the painting they are considering buying. “You want to see the provenance. You want to make sure you are getting what the dealer purports it to be,” he said. “Regardless of how much money I was going to invest, I would be cautious. I would not tell people not to do it, but they have to go with their eyes wide open and they have to be prepared to do the research on what you are going to buy.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.