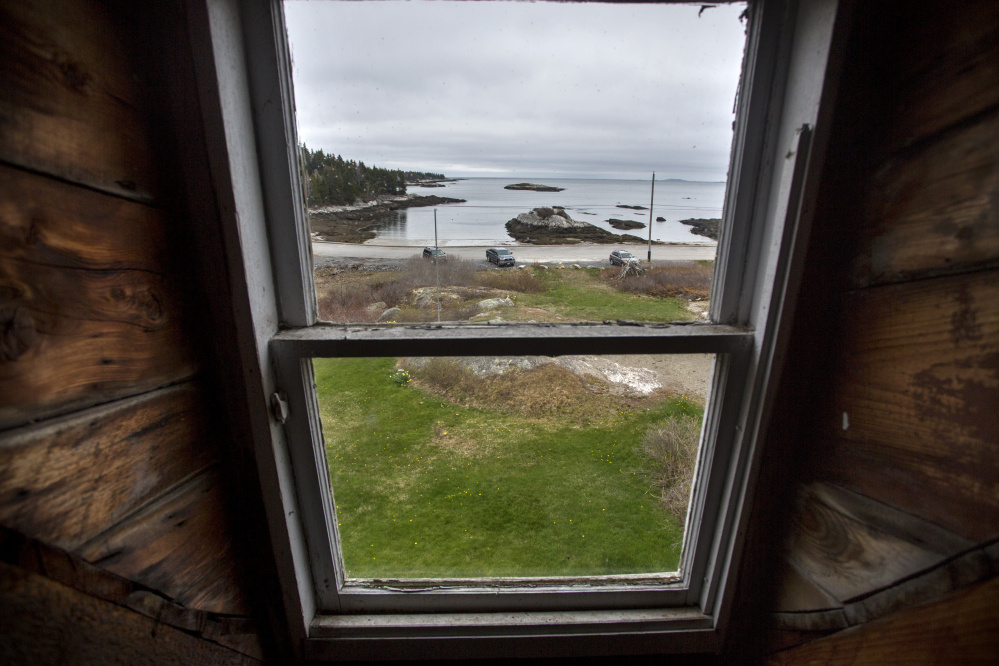

SOUTHPORT — The small piece of land and slightly rundown house sit just across the road from the only public beach in this small community southwest of Boothbay Harbor.

Nancy Prisk thought the 3-acre parcel, which is for sale by the town, was worth preserving, and she knew others who felt that way too. But mostly she worried about the possible alternative: a wealthy, out-of-state buyer who would develop the land and disrupt Southport’s quaint fabric.

It’s a fear that exists at some level in coastal communities from Kittery to Eastport.

So late last summer, Prisk went to the three-member board of selectmen for the town of about 600 year-round residents in Lincoln County. She knew she had to make a good offer, a reason not to sell the land to the highest bidder.

The select board eventually agreed to a deal: If Prisk and others could raise the money, the land was theirs. In turn, Prisk agreed that if her group did buy the land, it would commit to annual payments in lieu of taxes to offset any revenue the town might leave on the table.

The town offered a right of first refusal last November and the nonprofit group Land for Southport’s Future was born.

Prisk said the goal is to buy the property and preserve it as a public space. She hopes the house, which formerly belonged to local artist and cartographer Ruth Lepper Gardner, will be renovated and used by other artists.

But the real test will be whether the nascent group, which just received nonprofit status this month, can raise the $900,000 needed to purchase the parcel. Prisk has a three-member board of directors in place, a lengthy mailing list and plans for community events to share her plans.

“We’re serious about what we’re doing,” Prisk said in a recent interview. “This isn’t just a pool of neighbors trying to buy some land.”

The fight over land, especially high-value coastal land, is likely to be a major debate in Maine for the next several years and groups like this one could play a role.

Some feel Maine’s coastline is developed enough and don’t want to see it turned into another oceanfront enclave of mostly private beachfront.

Others, though, see Maine’s coastal land as valuable real estate that should be strategically marketed and sold to whoever can generate the most tax revenue in return.

Warren Whitney, land trust manager for Maine Coast Heritage Trust, said finding a balance of responsible development and land conservation is likely the best answer, but every community is a little different.

Whitney also said that while local support is crucial for land conservation, he cautioned that parochial groups like Prisk’s, which are created for a specific purpose but may not have staying power, may not be the best approach.

“The challenge in land conservation is creating an organization that can keep it going over the long haul,” he said.

Gerry Gamage, Southport’s first selectman, said the town’s main goal has simply been to sell the property because it can’t really afford to be a land holder.

“But we’re certainly happy to have a group like this own it,” he said of Land for Southport’s Future.

Prisk is optimistic, perhaps even idealistic, about her group’s chances, but she’s also excited to be part of the conversation over how Maine’s remaining coastal land is used.

“I hope others see what we’re doing,” she said.

A LOCAL VISION

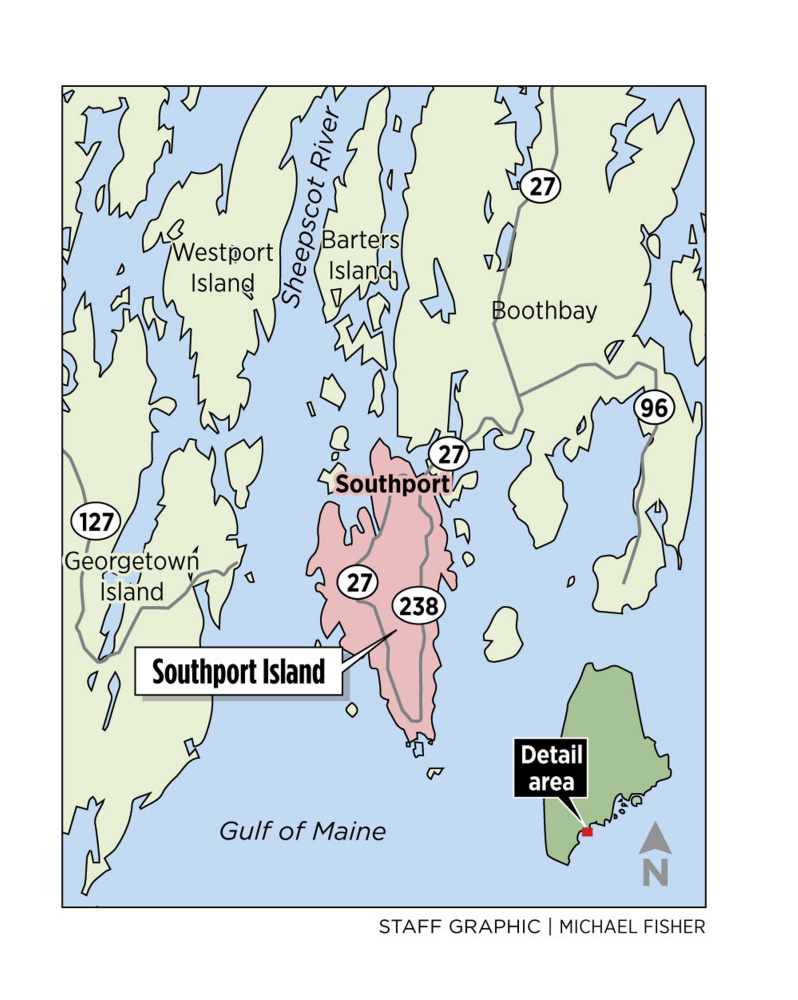

Southport, as well as its better-known neighbors Boothbay and Boothbay Harbor, is not on the busy Route 1 corridor that stretches from Maine’s southernmost point to the Canadian border. It doesn’t get the drive-by tourist traffic of Kennebunk, Old Orchard Beach, Camden or Belfast.

But Gamage, who has lived in Southport for all of his 62 years, said the town is no longer anonymous.

“People are finding us,” he said.

The town is technically an island, bordered on one side by Sheepscot Bay and on the other by Linekin Bay. Its waterfront edges are developed with a mix of high-end homes and modest ones that have been in families for generations. Many residents are seasonal but there is a sizable year-round contingent.

Southport’s wealthiest and most well-known resident is Paul Coulombe, the former owner of White Rock Distilleries in Lewiston, which he sold for more than $600 million to Jim Beam in 2012. Since Coulombe got out of the liquor business, he has built an 18,000-square-foot mansion on the western tip of Southport known as Pratts Island and has spread his wealth around the peninsula despite the unease of some locals who fear he might be changing the communities too much.

Prisk said she is well aware of Coulombe’s presence but hasn’t reached out to him to support her cause.

In some ways, the town has already preserved the most crucial piece of Ruth Lepper Gardner’s former property.

Gardner lived on Southport for decades, even before the bridge was built in 1939 connecting the island to the mainland. Although her property was private, she always allowed townspeople to use the beach – the only major beach on the mostly rocky-ledged island.

But after she passed away in 2011 at the age of 105, Gardner’s three nephews inherited the property and put it on the market. Townspeople worried that the sale would mean the loss of that beach and wondered, what if the town bought it instead?

In 2013, at a town meeting where residents voted by a show of hands, Southport approved the town’s purchase of the property for $1.25 million.

Gamage said the town was never going to be able to keep the property, so it split the land in two. The beach would remain public and the rest would be sold.

But Prisk said it’s not just the beach that deserves to be preserved. She said the island has done well over the years in retaining its identity and she believes the Gardner property is a part of that.

Southport already has some history in conservation.

The historic Hendricks Head Lighthouse was purchased in 1991 by a private owner, but that property has remained largely untouched.

The island also was home to the summer cottage of famed conservationist and author Rachel Carson. That property remains in Carson’s family but they often rent the cottage to writers, artists and environmental researchers.

Prisk said she has a similar vision for the Gardner house.

Although her endeavor is unique, Prisk is no stranger to fundraising and organizational support. She was among a small group of University of Maine alumni who launched the effort to build what is now the Buchanan Alumni House on the Orono campus.

THE FUTURE OF MAINE’S COAST

The effort to preserve the small piece of land and house on Southport is a microcosm of the broader debate over what will happen to the little remaining coastal land that is left.

A little ways up the coast, on Brewster Point near the Samoset Resort in Rockport, one piece of property had been marketed as a 45-lot subdivision for middle-class homes. After the property sat on the market, it eventually sold to an unnamed out-of-state buyer who dissolved the subdivision and informed the town that he would build a family compound there instead.

Prisk said that’s exactly what she doesn’t want to see happen on Southport.

But land conservation, in particular the state’s Land for Maine’s Future program, has become a polarizing political issue of late.

Republican Gov. Paul LePage has said he is not a fan of Land for Maine’s Future and has withheld voter-approved bonds to purchase land for the program in an effort to weaken the program, arguing that the property purchased through LMF is taken off the tax rolls and no longer generates revenue.

Whitney, the land trust manager for Maine Coast Heritage Trust, said the governor’s characterization of land trust programs is not really accurate. Most land trusts – though not all – provide payments to their communities in lieu of taxes, sometimes at the same level as property taxes.

Land for Maine’s Future has helped conserve more than 500,000 acres statewide, ranging from working forests to working waterfront. All projects must provide public access.

The Maine Land Trust Network includes roughly 90 trusts statewide. That number is actually decreasing, Whitney said, because communities are getting smarter about consolidating and pooling resources. Whitney said smaller organizations like the one Prisk founded are unusual because it takes a sustained effort over many years to keep them going.

That’s one of the reasons he worries about the Southport trust, although Whitney wasn’t critical of Prisk’s effort.

“All land trusts started at a kitchen table,” he said.

Whitney did say that now is a good time to conserve land because the real estate market is still slow to rebound. He said if the market does improve, land trusts will not have the resources to compete with private buyers. He said trusts and communities can sometimes fend that off by working with property owners long before they think of selling.

So far, no one has indicated interest in the Gardner property on Southport, but the right of first refusal won’t last forever. And if a buyer emerges and Prisk’s group hasn’t raised enough money, they lose that right.

“We don’t have the luxury of sitting on it forever,” Gamage said.

One of the major issues for land trusts and those interested in conservation is public access. There have been a number of legal battles over access, in Harpswell and Kennebunkport and Wells and elsewhere. The Harspwell case, which deals with access to Cedar Beach Road, was appealed to the Maine Supreme Judicial Court last December after a lower court in late 2014 allowed the public to use a road that had been blocked since 2011 when the landowners cut off access.

The Kennebunkport case, involving Goose Rocks Beach, also was settled by the state’s highest court in late 2014, although that decision left room for further litigation. The state Supreme Court updated an earlier decision that the public could use the beach with a decision that allows the town to argue on a parcel-by-parcel basis going forward.

Whitney said the Gardner property is a good example of access. It was a private property whose owner allowed public access. But properties change hands and sometimes new owners don’t want all that traffic.

Nick Ullo of the Boothbay Region Land Trust said he was never contacted by Prisk, which he said was unusual because his trust manages other land on Southport, including the Hendrick’s Head preserve, which is adjacent to the Gardner property. Although he said the Boothbay land trust’s interest in the property would be minimal, he’s not sure it’s a good idea to have a competing group.

Prisk said she formed her nonprofit to be specific to Southport, not to a region. She wants that sense of local control.

“I’m extremely confident about our ability to raise money,” she said. “I’ve listened to people. The idea of preserving space is really important.”

CORRECTION: This story was updated at 10:01 a.m. on June 6, 2016 to clarify that Hendricks Head Lighthouse is not open to visitors.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.