Jewett Williams was 21 years old in 1864 when the reach of the Civil War found him in Hodgdon, a smudge of a town along the Canadian border in Aroostook County.

Drafted and mustered, Williams joined the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment and soon found himself on the front lines of the war, now in its final throes. He survived eight major battles, and was present when Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at the Appomattox Court House in Virginia.

But Williams’ story – and his role in one of the most celebrated units of the Civil War – was nearly lost forever until a Maine historian stumbled across records last year that showed he died alone in an Oregon mental institution in 1922, his body cremated and then forgotten for nearly a century.

“They cremated the remains, put him on a shelf, and waited for the family to pick it up, and no one did,” said Thomas Desjardin, former Maine education commissioner and a longtime Civil War historian who has spent 40 years studying the 20th Maine and its soldiers.

Now, with the help of Desjardin and several private citizens and public officials, Williams’ ashes will be returned to the Togus National Cemetery in Chelsea, where he will finally rest beside his fellow soldiers.

Williams’ remains will wind their way across the country courtesy of the Patriot Guard Riders, a national volunteer group of motorcyclists who help honor fallen soldiers. The remains will be handed off to members of the Oregon chapter, who will ferry Williams’ remains east, passing them from one state’s club to the next.

“It’s kind of a Pony Express transfer,” said Mike Edgecomb, the leader of the Maine Patriot Guard Riders.

The route is being finalized, but the plan calls for Edgecomb to meet up with Williams’ remains in Appomattox before heading north. The remains are expected to arrive around Aug. 22. An interment ceremony, complete with a Civil War-era color guard, is planned for Sept. 17.

Williams also will get a send-off ceremony Monday morning at the Oregon State Hospital Memorial in Salem, with Civil War re-enactors, before his remains are transferred to the Patriot Guard Riders.

The journey to get Williams home has taken 18 months of on-again, off-again planning since Desjardin discovered Williams’ connection to Maine in 2015. At the time, Desjardin was also serving as the acting education commissioner, and in his spare time was researching a book on the lives of 20th Maine soldiers, methodically combing old records to pinpoint where each of the unit’s 1,500 soldiers was buried.

Unknown to Desjardin, health officials in Oregon already had been doing plenty of historical scouring of their own, trying to find the rightful homes for the remains of nearly 3,500 patients who had died at the Oregon State Hospital for the Insane.

In 2004, hospital staff stumbled onto a cache of nearly 3,500 copper urns secreted away in a locked shed on the hospital grounds. Each urn contained the ashes of former patients who had never received proper burial.

Urns containing ashes of patients who died at the Oregon State Hospital sit on the shelves decades later. The Patriot Guard Riders will ferry Jewett Williams’ ashes back to Maine. Rob Finch/The Oregonian

The discovery was a bombshell, and stood as a symbol of the longstanding marginalization and mistreatment of the mentally ill, sparking Oregon to invest millions of dollars into improving care for the mentally ill. The Oregonian newspaper won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize in Editorial Writing for editorials about abuses that took place in the mental hospital.

“It was a gut-check moment, a watershed moment for reform of the hospital,” said Tyler Franke, a spokesman for the Oregon Department of Veterans Affairs.

Oregon state lawmakers also began the slow, painstaking process of cataloging and taking inventory of the names and identities of the deceased.

Franke said officials are still working their way through all the remains to search for surviving relatives, but the process has been difficult.

Oregon-based researchers assembled a history of Williams’ life, including details of his military service with the 20th Maine and his family life, which included two marriages and a post-war life spent steadily moving west.

After the war, Williams mustered out in Portland on July 16, 1865.

He returned to Aroostook County and married a woman named Emma, but they divorced in 1871. That same year, Williams moved to Minnesota and married again, this time to Nora Carey, in Minneapolis.

Together they had six children, and by 1885, had settled in Brainerd, Minnesota.

That marriage also didn’t last, and by 1889, Nora was listed as a “widow” in the city directory of St. Paul, but the couple apparently reunited and moved to Washington state by 1892.

“He kept moving to where the land was cheap and where population was growing,” Desjardin said. “This happened with a lot of men. They saw Virginia (where) the fields are flat and not full of rocks.”

But Williams’ family life frayed once again, according to the 1900 census, which showed he was working part time as a carpenter and renting out rooms to several boarders. His wife was listed as living about 9 miles away.

By 1919, Williams had apparently moved to Oregon, and was among a group of Civil War veterans who spoke at schools in the Portland area, local newspapers reported at the time.

In 1920, at the time of the census, Williams was estranged from his wife and was listed as a widower in Portland. He told census-takers that he worked as a common laborer, even at 75.

Two years later, on April 14, 1922, Williams was admitted to what was then called the Oregon State Hospital for the Insane in Salem. The “reason for insanity” was listed as senility.

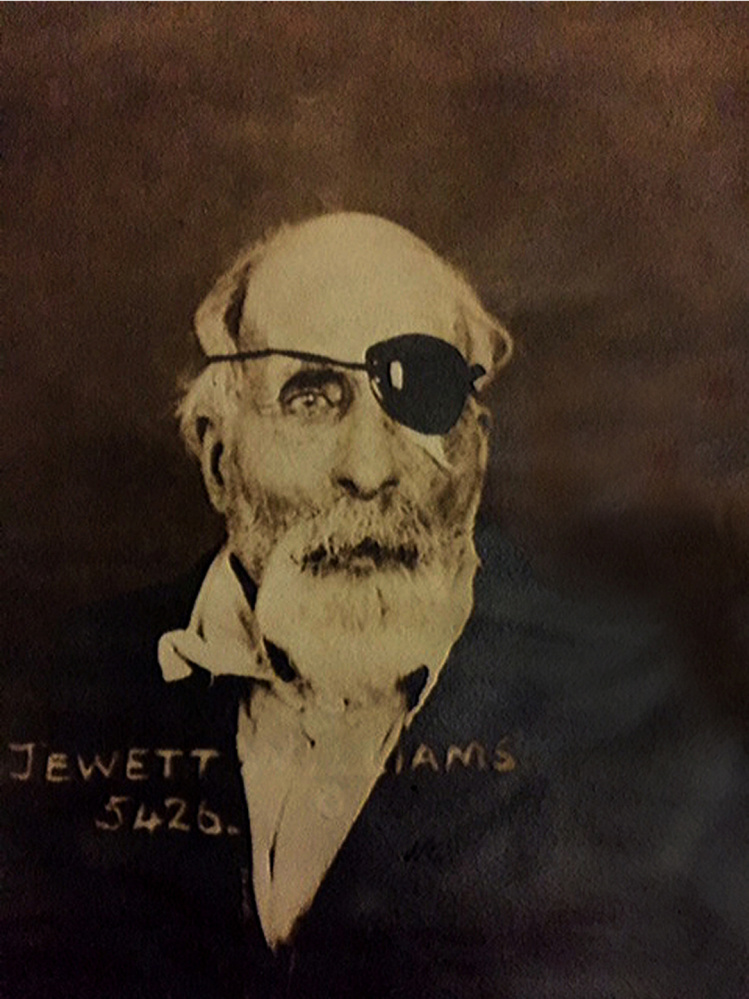

A hospital photograph shows him bearded and with an eye patch, his name and a number scratched into the print.

He died at the hospital two months later at the age of 78, cremated and forgotten for nearly 90 years.

“He outlived everyone (in his family), as far as we can determine,” Desjardin said. “For all we know, he never wanted to come back to Maine. He left after the war and never came back.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.