Maine’s wind power industry is poised to see its biggest period of growth since the state’s first major project was built six years ago, a surge brought on by unprecedented demand for renewable energy in southern New England and by evolving technology that has lowered the cost of producing electricity.

Recent laws in Massachusetts and Connecticut have compelled utilities to seek proposals from developers of renewable energy projects. Dozens of potential ventures competed, including solar and tidal energy. In the end, utilities chose mostly wind projects, mostly in Maine.

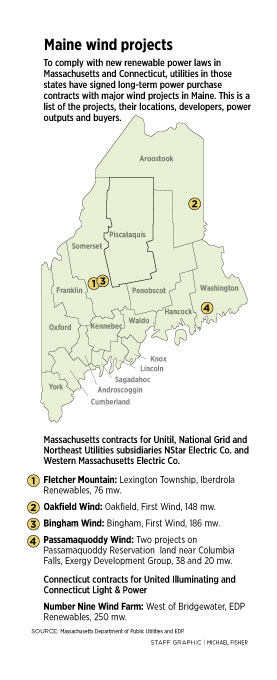

Massachusetts companies signed power-purchase agreements for a total of 565 megawatts, enough energy to power 170,000 homes. Roughly 488 megawatts of that would come from five wind farms in Maine. They are in Oakfield, Lexington Township and Bingham, along with two near Columbia Falls.

Connecticut, which set a goal of getting 20 percent of its electricity from renewable sources by 2020, signed a long-term contract with a proposed wind farm west of Bridgewater in Aroostook County that will have a capacity of 250 megawatts. With an investment estimated at up to $500 million, it would be the largest project ever built in New England.

These projects are expected to come online within three years. The deals still need approvals from state regulators, and some still lack all of their needed permits in Maine. But they were announced quickly late last month, because developers are under time pressure to start some work before the end of the year, when a critical federal tax credit expires.

Utilities and energy officials say they selected the projects because wind now can produce power near the cost of electricity from natural gas, the dominant generation source in the region. Until recently, wind hasn’t been able to compete on price with gas-powered electricity in New England. To the extent that the equation has changed, it means the industry in Maine may be poised to see continued growth, and the construction jobs and investment that come with it.

“We’re very focused on price,” said Dennis Schain, a spokesman for the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. “We want cleaner power, but we want it cheaper.”

In Massachusetts, utilities estimated that customers would save between 75 cents and $1 a month if the contracts were approved. The Associated Industries of Massachusetts told The Boston Globe that the state can benefit from this competitively priced renewable power.

Wind energy in Maine has attracted roughly $1 billion in investment, according to industry calculations. But the prospect of a new construction boom isn’t being welcomed by Gov. Paul LePage, who has been a vocal critic of the cost of wind energy.

For one thing, the negotiated rates aren’t as low as they seem, according to Patrick Woodcock, the governor’s energy director, because of the added cost of upgrading transmission lines. Beyond that, he said, out-of-state power agreements don’t help Mainers with their high energy bills, which could be lower if wind had more competition from Canadian hydro and new biomass plants.

“Wind is not the only option for renewable energy generation in New England,” he said.

The goals in Connecticut and Massachusetts are a new nightmare for wind-power opponents in Maine, who have been protesting since the Boston company now as known as First Wind built a 42-megawatt project at Mars Hill in 2007. They complain that Maine sees few benefits for having giant towers and turbines sprouting from ridgelines across the state. Now they expect to see hundreds more, and say they will fight any permit approvals.

“This is just the tip of the iceberg,” said Steve Thurston, a spokesman for the Citizens’ Task Force on Wind Power. “Maine is going to be a plantation of wind turbines to serve the needs of residents in other states.”

In Connecticut, Schain said his state recently tweaked a renewable energy law to seek proposals from Canadian hydro power, if the 2020 target can’t be met with the newly signed contracts. It also plans to seek proposals for new, cleaner-burning biomass plants. As part of the current process, utilities also signed a long-term contract with a 20-megawatt solar electric farm in eastern Connecticut, which would be the largest in New England. But in general, Schain said, the state doesn’t have the space or the wind resource for the grid-scale projects that Maine does.

“We understand there are local sensitivities,” Schain said. “We expect these projects will be developed in the most environmentally sensitive manner possible.”

The Maine project that will serve Connecticut utilities is being proposed by EDP Renewables North America, a subsidiary of Energias de Portugal. It operates 3,700 mw of wind in 11 states and has U.S. headquarters in Houston. It’s planning to open an office in Presque Isle before year’s end and has begun meeting with residents and town officials in the project area.

The project, known as Number Nine Wind Farm, would be located in unorganized territories nine miles west of Bridgewater. It was first proposed by now-defunct Horizon Wind Energy, in 2007. Adam Renz, an EDP spokesman, said the power purchase contract and commitment to build a high-voltage line to connect the project with the New England grid, make it feasible now.

States including Maine have been encouraging renewable power development for three decades, by approving premium rates. The idea was to reduce dependence on oil, gas and coal, but the trade-off was higher bills for homes and businesses.

That’s why last month’s announcements of the power contracts in Massachusetts and Connecticut came as a surprise to many. While keeping the details confidential, officials said wholesale energy rates will hover in the 8 cents per kilowatt hour range over 15 to 20 years. That’s just above today’s cost of natural gas generation in Connecticut, according to Schain.

The long-term contracts will lower financing costs for developers, but the real breakthrough has come from technology, according to Matt Kearns, vice president for business development at First Wind. Better materials and designs allow companies to put up taller towers with bigger blades, which means more power output at lower wind speeds.

“The trend,” Kearns said, “Is larger installed capacity on a per-turbine basis.”

The trend is apparent at four First Wind projects in Maine.

The Rollins project in Lincoln was built in 2010, and is rated at 60 mw. It features 40 turbines that can generate 1.5 megawatts each. The top blade height from the ground is 389 feet, more than twice as tall as One City Center in Portland.

The Bull Hill project in Hancock County, completed last year, is rated at 34 mw. It has 19 turbines that can generate 1.8 mw each. The blade tip is 475 feet off the ground. This project won a contract during a first round of utility bids in Massachusetts.

For the latest contracts, First Wind won for two projects that would be among the largest in New England, a 147 mw wind farm in Oakfield and a 186 mw farm in Bingham. They would use 3 megawatt turbines – 49 of them at Oakfield and 62 at Bingham – with similar blade heights as at Bull Hill.

“Onshore wind has never been cheaper,” Kearns said. “It represents an opportunity for ratepayers to save an enormous amount of money. That’s why Massachusetts is buying it. Industrial customers wouldn’t say they were pleased, if they weren’t.”

The cost, according to Kearns, includes the 59-mile lead line from southern Aroostook County to Chester, to hook up the Oakfield project with the New England grid. EDP Renewables also will need to build a line to Haynesville, roughly 40 miles away, to get its energy onto the grid.

But wind opponents say these generator lines don’t account for the added costs that ratepayers across the region will bear to beef up transmission lines. Major wind projects are located far from population centers in New England, and new investments will be needed to move the power south from Maine and maintain a stable and reliable grid.

Also, wind power is intermittent. These Maine projects are likely to have capacity factors in the 30 percent range, a measure of how much electricity a turbine actually produces over a year, compared to its maximum design if the wind blew all the time.

“Transmission is the elephant in the room,” said Chris O’Neil, an attorney who represents Friends of Maine’s Mountains. “Grid reliability and stability is going to suffer, and it will be very expensive to either fix or deal with.”

The issue of how to integrate growing amounts of wind, while balancing ratepayer cost and system reliability, already is under study by the region’s grid operator. These power purchase agreements add new urgency to ISO-New England’s task.

The role of wind power could be tempered by more imported hydroelectricity from Canada. But advocates of Canadian hydro, such as LePage, downplay the difficulties of building new transmission corridors needed to move the energy.

Utilities recognize the challenge, however. Northeast Utilities, one of the major power companies signing the Massachusetts and Connecticut wind contracts, has been blocked for three years by conservation groups from building the Northern Pass line through New Hampshire, to import power from Hydro Quebec. A competing corridor proposal called the Northeast Energy Link, led by National Grid and the Canadian parent company of Bangor Hydro, would move wind and hydroelectricity through Maine along the interstate and Maine Turnpike.

But even if these projects gain traction soon, more wind likely will be required to meet southern New England’s renewable power goals. Look for much of it to come from Maine.

Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or:

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.