CASCO BAY – Peter Stocks displays what looks like a bit of mud in the palm of his hand and gently swirls it with a fingertip.

With careful tending over the next 16 months, the tiny brown seeds would grow into a few dozen succulent mussels worthy of a creamy chowder or a lemon-garlic sauce.

But Stocks won’t have to wait that long. In September, the former corporate lawyer anticipates harvesting the first 1,500 to 2,000 pounds of rope-grown mussels from his newly licensed rafts off Little Chebeague Island.

He holds one of his young mussels, its inch-long, deep-blue shell glistening in the July sun, and recites a sort of ode to the pointed bivalve that has consumed much of his time over the past year.

“These are amazing animals,” Stocks says. “You don’t do anything to them. You don’t medicate them. You don’t feed them. You just let them grow, pull them up and send them to market.”

Rest assured, there’s a lot more to it than that.

Stocks and his wife, Lynda, who live in South Portland, own the latest aquaculture venture in nutrient-rich Casco Bay, where about a dozen ocean farmers are combating fickle weather and ravenous eider ducks to cultivate an industry they say has plenty of room to grow in Maine.

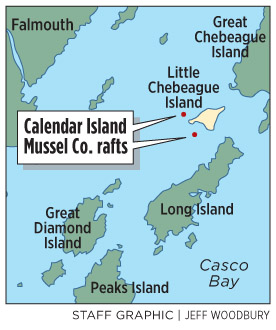

The Calendar Island Mussel Co. — named after an old term for the Casco Bay islands — joins similar aquaculture operations near Clapboard, Bangs and Basket islands, in the western part of the bay, that are growing mussels, oysters and seaweed.

They’d like to make a dent in shocking international trade statistics that show about 85 percent of seafood sold in the United States comes from other countries, and about half of the imported seafood is farm-raised. Shrimp from Thailand. Salmon from Norway. Mussels from Chile.

“We spend about $10 billion annually on seafood from other countries, which makes it the second- or third-largest contributor to our international trade deficit, after oil and sometimes automobiles,” said Sebastian Belle, executive director of the Maine Aquaculture Association.

About 70 percent of mussels sold in Maine come from the Canadian Maritimes, including Prince Edward Island, where 1,500 people are employed to produce about 60 million pounds of rope-grown mussels each year, Belle said. In contrast, Maine produces about 1.3 million pounds of rope-grown mussels annually, employing fewer than 100 people.

“There’s plenty of room for expansion without impacting other uses,” Belle said.

YACHT CLUB’S CONCERNS

Still, some aquaculture operations face opposition, including the Calendar Island Mussel Co.

The Stocks have two growing sites, each consisting of four large rafts located off the western tip of Little Chebeague Island, in the waters of Long Island.

The rafts, each held in place by 12 tons of concrete blocks and massive chains, are properly located according to leases issued by the Maine Department of Marine Resources, said Tom Hale, an officer with the Maine Marine Patrol. They’re also properly marked, with solar-powered lights, radar reflectors and white buoys that meet federal maritime requirements, Hale said.

In addition, the raft sites were reviewed and approved by several federal agencies, including the U.S. Coast Guard, and were supported by Long Island lobstermen and residents following a public hearing last fall, Peter Stock said.

But while the rafts aren’t located in an official navigational channel, several members of the Portland Yacht Club in Falmouth have complained about the larger set of rafts that was installed in April. It lies within a commonly traveled recreational boating course around the northern tip of Clapboard Island to Chandler Cove, just east of Little Chebeague Island.

“Several members have concerns about the location of the floats, but not the aesthetics,” said Jennifer Yahr, commodore of the yacht club.

“We support the marine industry, but the location is a navigational hazard.”

Yahr said the yacht club plans to accept Stocks’ offer to meet with members in the next week or so to address their concerns.

Falmouth Harbormaster Alan Twombley said he received one complaint about the rafts, so he issued a boater-safety warning last month, even though the rafts aren’t in Falmouth waters. He said concern about the rafts will likely fade as boaters learn where they are located and adjust their course.

‘AWESOME’ CASCO BAY

In the meantime, Stocks and his harvest manager, Bernie Sutherland of Portland, are tending the rafts almost daily. Stocks hired Sutherland for his experience — he worked for eight years with the nearby Bangs Island Mussel Co., which started in 1990.

Sutherland, 34, is famous for knowing when mussels are “happy.” He straddles two beams on one of the 40-by-40-foot rafts and pulls up the end of an 80-foot-long rope that’s strung below. The rope is covered with small, dark mussels, each one attached by its byssal threads or “beards.” They hang in about 50 feet of water at low tide, which allows them to filter nutrients easily from the bay and concentrate their energy on growing more meat and less shell. Deep nets wrap each raft to keep hungry ducks away.

“It’s a good year,” Sutherland says. “It’s a new site and the cold water of Casco Bay is awesome for growing mussels.”

Stocks and his wife, Lynda, a native of Ireland who works in advertising, spent several months researching mussel growing as a new business venture. They have two children and met when Stocks, who grew up in Cape Elizabeth, was attending the London School of Economics. Before moving back to the States in 2007, they started a duck-boat tour company in Dublin, which they operated for several years before selling.

“We wanted to do something where we could stay in Maine, that would be environmentally sustainable and involve a renewable resource, and would put some people to work,” says Stocks, 51. “I also like being on the water, and I wanted to do something that if, God forbid, I died on the job, I’d be happy doing it.”

The Stocks have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on permits, building materials and equipment, including a lobster boat and mussel-processing machines. When they sell their first batch of mussels in September, they’ll likely get $1.50 to $1.85 per pound.

Once their mussel rafts are producing regular batches, they anticipate harvesting 300,000 pounds annually and getting as much as $550,000 from buyers.

They hope to capitalize on Maine’s reputation for producing the meatiest mussels in the world. They’d like to put Calendar Island Mussels on dinner tables across the country.

“The Maine brand is very valuable,” Stocks says. “Casco Bay is known as a source of clean, quality product. We’ve already heard from several distributors who want a consistent supply.”

Staff Writer Kelley Bouchard can be contacted at 791-6328 or at:

kbouchard@pressherald.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.