We are well into “Where to Draw the Line: The Maine Drawing Project,” a year-long series of exhibitions dedicated to drawing. A statewide project, it touches many places and times. I report on two that bear on my thoughts about current drawing in Maine.

The Farnsworth — which has been holding project-related events since January — offers “Four in Maine: Drawings” among other presentations. Its four are Mary Barnes, Emily Brown, T. Allen Lawson and John Moore. A generous event in size and range, it articulates on what is going on in much of Maine these days. I present its work in the order that I saw it.

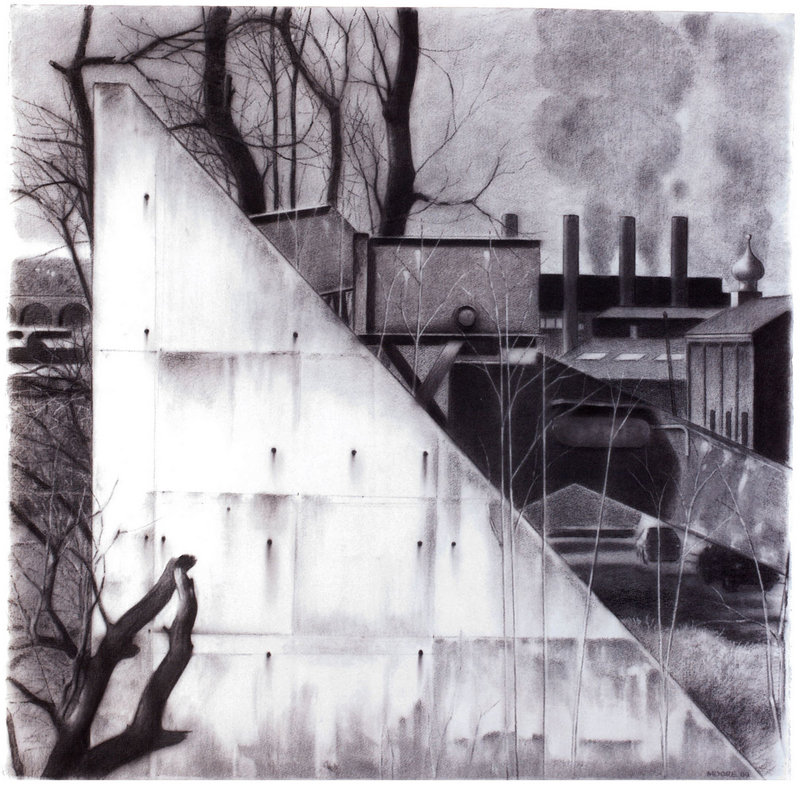

John Moore’s drawings in charcoal have the force of his concerns. The thrust is the erosion of the industrial environment. His medium is less selective than, say, graphite and tears into the subject in a manner coincident with its rawness.

In “Slab,” for example, heavy factory buildings in the company of blitzed trees slice into the sky and chew up anything that is beneficial to the world around it. And, in the event you miss the point, Moore adds the remaining angle of Thomaston’s old Maine State Prison wall to his composition. Moore’s “Fence” carries the same weight. Stacks, factories and an unloved volunteer tree are embraced by a chain-link fence. As in “Slab,” we decline into a world in which the sun does not intend to reappear.

T. Allen Lawson is a master of the enchantments in the landscape. In some works, he touches the exquisite. I am not familiar with his drawings, but in this show — working in chalk, charcoal or pencil — he reaches levels that are as quietly seductive as anything I have seen in a long time.

In his graphite drawings of trees and in his “Study for Morning at Martinville,” or in the more complex “Shorter Days,” I find landscapes as responsive to ordained order in the physical world as the heart could wish. Their certainty and restraint urge the sense of the sublime within me.

Mary Barnes’ work is singular. In graphite, ink, paint and pastel she forms irregular primal units which, in time, increase and enlarge to occupy the full surface of a work, sometimes in networks, sometimes in waves. It is a matter of growth, of organic enlargement, of activity. Indeed, in terms of animation, these drawings dance for the viewer. Whether the more sedate “Lichen” or the explosive “Fungus,” they are never at rest.

All of this can be invaded by tiny creatures whose purpose is not explained but seems ominous. The more you look, the more sinister the possibilities.

Emily Brown is the least draftsman-like of the makers of drawings in this show. Her works congregate photographs, wallpaper, cigarette wrappers, etchings, lithographs and the like, sometimes of or from her own work, sometimes obtained from others into images that have a rapid pulse.

In “Handstand,” for example, almost all the media I have mentioned, plus ink and wash, join to become a sylvan background for a lakeside retreat, complete with a shelter and a descriptive postcard. It’s both handsome and funny.

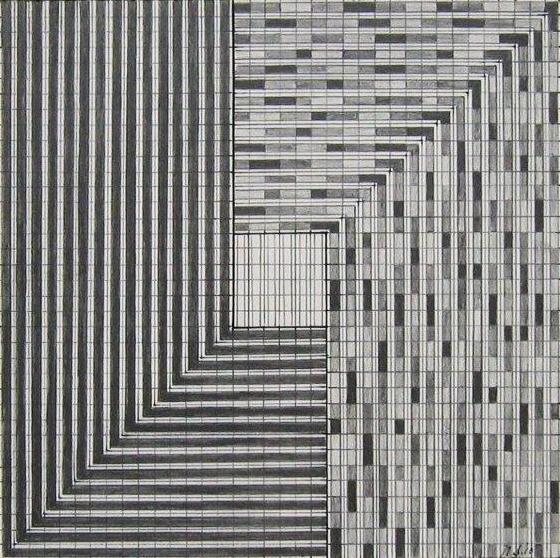

The current show at June Fitzpatrick High Street is an opportunity to see two from a group of masterworks produced by Noriko Sakanishi. Each is a 20-inch by 30-inch graphite and pigment drawing meticulously logical and infinitely complex.

The mastery lies in the balancing of these qualities. Lines parade across the streets in perfect definition but at independent densities. The independence does not lessen the sense of logic — that controls throughout — but, rather, contributes a pulse to the drawings, a quality that is not common in work of geometric abstraction.

So deft is the pulse that you can almost anticipate its passage, much as can be done with passages in music. I don’t want to make too much of the anticipatory notion, but when the elements of a work are so ineluctable to one another, the resulting harmonies make easy parallels to other arts.

These are wonderful drawings and in this show are accompanied by a group of smaller works similarly constructed, but confronted by bold and adversarial forms. Some adversaries tilt the axis of the plane, some remove segments from it and some overlay it with such force that portions are extinguished. Unlike the lyrical larger works, there is a tension in them that harkens to Sakanishi’s well-known three-dimensional pieces. They have remarkable presence for work of their scale.

I understand there has been talk about whether I would review the current show at Addison Woolley because it’s not my thing. I have no idea what my thing is, but I wouldn’t have missed this show for the world.

It’s a two-part event, one is “Surreallegories: Three from 2010” by Darrell Taylor. The other is “Ephemeral Nature” by Fran Vita-Taylor.

Vita-Taylor’s color digital prints are portentous. They speak as trophies of uncertain events to come. Gathered on black backgrounds, they are of leafs, vegetables, other bits of natural history such as milkweed, a mask and assortments that make reference to the writings of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Roman trophies are about what was; these are about what might happen. They are gorgeous and a little spooky.

Darrell Taylor’s “Surreallegories” are offered as “very large-scale photocollage murals” and, at 24 inches by 106 inches they are that. Their size is not, however, the point. It’s what’s going on in them that makes them fascinating.

Borrowing from William Blake, one of the Van Eycks, Dorothea Lange, Diane Aubus, the rotunda of the Capitol, the Dubai Tower, industrial boilerplate, filth from the mind of Hitler, slave work in other places, congregations of cardinals, family photographs and uncountable other sources, some of which you pick up on and forget when you go on to the next source, they are witty, clever and philosophic.

In them, Taylor has put together a group of seamless digital works whose full contents are going to be beyond your power to extract, but whose fascination has no obvious limits. Surrealism may be making a comeback, this time a lot smarter.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 46 years. He can be contacted at:

pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.