LOS ANGELES – After his beating by police stunned the nation and a jury’s decision not to hold them responsible sparked a deadly race riot that left Los Angeles smoldering, Rodney King in a quavering voice pleaded on national television for peace while the city burned.

But peace never quite came for King — not after the fires died down, after two of the officers who broke his skull multiple times were punished in a different court, after race relations were reshaped and police tactics were reformed.

His life, which ended Sunday at age 47 after he was pulled from the bottom of his swimming pool, was a continual struggle even as the city he helped change moved on.

STRUGGLING WITH ADDICTION

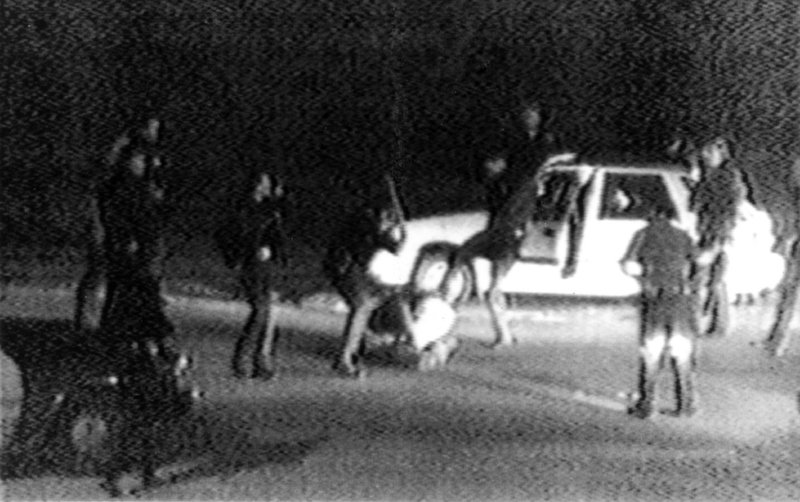

The images — preserved on an infamous grainy video — of the black driver curled up on the ground while four white officers clubbed him more than 50 times with batons — became a national symbol of police brutality in 1991.

More than a year later, when the officers’ acquittals touched off one of the most destructive race riots in history, his scarred face and softspoken question — “Can we all get along?” — spurred the nation to confront its difficult racial history.

But while Los Angeles race relations and the city’s police department made strides forward, King kept coming before police and courts, struggling with alcohol addiction and arrests, periodically re-appearing publicly for a stint on “Celebrity Rehab” or a celebrity boxing match.

He spent his last months promoting a memoir he titled “The Riot Within: From Rebellion to Redemption.”

King was declared dead at a hospital after his fiancee, Cynthia Kelley, called 911 at 5:25 a.m. to say that she had found him submerged in the pool at his home in Rialto, about an hour’s drive from Los Angeles. Officers found King in the deep end of the pool, pulled him out and tried unsuccessfully to revive him with CPR.

According to Capt. Randy De Anda, Kelley told police that King was an “avid swimmer,” but that she was not.

An autopsy was expected to determine the cause of death within two days; police found neither alcohol nor drug paraphernalia near the pool and said foul play wasn’t suspected.

King’s death was a grim ending to a saga that began 21 years earlier when he fled from police after he was stopped for speeding.

The 25-year-old King, on parole from a robbery conviction, had been drinking, which he later said led him to try to evade police. He was finally stopped by four Los Angeles police officers who struck him more than 50 times with their batons, kicked him and shot him with stun guns. He was left with 11 skull fractures, a broken eye socket and facial nerve damage.

ACQUITTAL, THEN UNPRECEDENTED RIOTS

A man who had quietly stepped outside his home to observe the commotion videotaped most of it and turned a copy over to a TV station. It was played over and over for the following year, inflaming racial tensions across the country.

It seemed that the videotape would be the key evidence to a guilty verdict against the officers, whose felony assault trial was moved to the predominantly white suburb of Simi Valley, Calif.

Instead, on April 29, 1992, a jury with no black members acquitted three of the officers on state charges in the beating; a mistrial was declared for a fourth.

Violence erupted immediately, starting in Los Angeles, and lasted for three days, killing 55 people, injuring more than 2,000 people and setting swaths of Los Angeles aflame, causing $1 billion in damage.

Police, seemingly caught off-guard, were quickly outnumbered by rioters and retreated. As the uprising spread to the city’s Koreatown area, shop owners armed themselves and engaged in running gun battles with looters.

King — who said in his memoir that FBI agents had urged him to keep a low profile if the officers were acquitted, expecting violence — appeared at a news conference on the third day, asking for an end to the uprising.

“People, I just want to say — can we all get along? Can we get along? … We’ve got enough smog here in Los Angeles, let alone to deal with the setting of these fires and things. … It’s not right, and it’s not going to change anything. … We’ve got to quit.”

Those words, particularly the phrase about getting along, have become part of the popular culture and have helped to keep his name, and the events of 1992, alive in American consciousness.

Although the four officers who beat King — Stacey Koon, Theodore Briseno, Timothy Wind and Laurence Powell — were not convicted of state charges, Koon and Powell were convicted of federal civil rights charges and were sentenced to more than two years in prison.

King received a $3.8 million civil judgment; Kelley, who later became his fiancee, was one of the jurors in the case.

But he quickly lost the money as he invested in a record label and other failed ventures. He was arrested multiple times for drunken driving — including last summer in Riverside, Calif.

BACK IN THE SPOTLIGHT

Despite his troubles, King remained upbeat as he confronted the 20-year anniversary of the Los Angeles riots and considered his legacy.

“America’s been good to me after I paid the price and stayed alive through it all,” he told The Associated Press earlier this year. “This part of my life is the easy part now.”

He had three daughters — one from an early relationship, one from his first marriage and one from his second marriage — and was engaged to Kelley.

He returned to the spotlight earlier this year as historians and news outlets explored the impact of the riots on its 20th anniversary, including the reforms made by the Los Angeles Police Department.

“Through all that he had gone through with his beating and his personal demons he was never one to not call for reconciliation and for people to overcome and forgive,” the Rev. Al Sharpton said Sunday. “History will record that it was Rodney King’s beating and his actions that made America deal with the excessive misconduct of law enforcement.”

Attorney Harland Braun, who represented one of the police officers, Briseno, in his federal trial, said King’s case never would have gained the prominence it did without the videotape.

“If there hadn’t been a video, there would have never been a case,” Braun said. “In those days, you might have claimed excessive force but there would have been no way to prove it.”

He saw King as “a sad figure swept up into something bigger than he was.

“He wasn’t a hero or a villain.”

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.