LEWISTON — Katrina LaCourse sits on the stack of blankets where she sleeps, leafing through the paperwork that could spell the undoing of her cobbled-together life.

Since August, she has been among the roughly 225 monthly recipients of General Assistance in Lewiston, where city officials have stepped up enforcement of eligibility rules, promising to prosecute violators.

On Friday, the city informed LaCourse, 47, that starting April 15, she would be cast from the welfare rolls for 120 days, eliminating the $420 in rent vouchers that keep her from living on the streets.

In the notification, officials say she willfully and falsely represented her eligibility, and that she did not report a roommate. She has not been summonsed, but she plans to challenge the allegations and the benefits cancellation.

“There’s nothing I did wrong,” said LaCourse, who will meet with the city Friday to explore her options. “I don’t know what’s going to happen to me.”

Mayor Robert Macdonald’s highly visible announcement Tuesday that his administration purged 84 welfare recipients from the system, including 50 for alleged fraud, highlight how Lewiston is attempting to shed the perception that its system is easy to game.

Skip Girouard, 76, who said he works seven days a week in his flower shop on Lisbon Street, applauded the initiative, and hopes the city will pursue jail time for convicted offenders.

“Lewiston is known as a place you can get welfare,” he said. “It’s sad. I think Macdonald is trying to straighten out the reputation.”

The enforcement initiative also pleased Debra Clarke, 56. Clarke oversees a crew that sweeps city streets, shovels snow and cleans parks in exchange for the rent vouchers. Additionally, each worker must apply to six jobs every week and attend career classes as part of the “workfare” program.

She said that in the past four months, she’s seen an improvement in the quality of the workers the city sends her way. Previously, Clarke said, some of the volunteers were unwilling to labor for their rent, exhibiting an attitude of entitlement.

“It’s a vicious circle,” she said. “They were brought up on welfare and don’t know any better. You can’t expect everyone to do everything for you.”

One of the workers who donned an orange vest that day was Josh Emerson, 29, of Lewiston, who was incarcerated for 13 months after he was found guilty of a 2010 assault. Free since Jan. 20, Emerson has been in the program for about a month.

The assistance covers his rent, heat, and even provides $20 a month for personal items. It’s not his first time receiving assistance. He was enrolled about three years ago, he said, and has noticed that the requirements have become more stringent since then.

“They used to be real lenient on a lot of things,” said Emerson. “But I guess they’re cracking down.”

He and others on assistancewere among the dozens who lined up for a hot lunch Wednesday at Trinity Episcopal Church. Some who are on workfare earn their housing vouchers by cooking in the kitchen.

About 35 of the volunteers help serve the meals, said C.J. Jacobs, the kitchen manager, one of the few full-time employees at the church. Jacobs said some of the workfare volunteers earn food-service credentials that could help them find employment.

But the job market remains tough.

Erin Reed, development director at the Jubilee Center, said that in a single day she sometimes will help complete 20 applications, often to no avail.

“We’ve lost a lot of great jobs,” said Reed, spooning baked chicken, boiled hotdogs, gravy and pasta onto Styrofoam trays for people streaming through the brightly lit kitchen.

Reed said she wished the city could do more to help people find work and, the allegations of fraud notwithstanding, said demand for services remains high, noting that 1,000 families are enrolled in a food pantry program.

“Maybe there’s fraud, but we don’t see it here,” said Reed, who lauded the workfare volunteers as hard-working and honest.

“I don’t know what I’d do without this crew.”

General assistance aid is a safety net of last resort for people who cannot afford basic necessities such as food, shelter or medication. The program, which is mandated by state law, is administered by municipalities, though the bulk of the cost is paid for by the state.

Last year, $13.23 million of the nearly $17.5 million in assistance came from state coffers, according to the state Department of Health and Human Services.

Gov. Paul LePage has targeted the line-item in his biennial budget, proposing to cap the cost at $10.17 million statewide, part of a plan to bridge a $112 million gap in the Department of Health and Human Services budget.

In Portland, the state’s largest provider of the aid, fraud cases in the last year represented 3 percent of 2,171 cases, or 103 instances. During the six-week period of investigation in Lewiston that ended Feb. 25, the city examined about 350 cases and found a fraud rate closer to 15 percent, said Sue Charron, Lewiston Director of Social Services.

Of the 50 fraud cases, Charron said 35 were applicants who allegedly falsified forms that are supposed to document where recipients are seeking work. Some had made up businesses or claimed they applied to a business when they never did. The other 15 were cited for falsely claiming they had no assets or income, or for other infractions. The remaining 34 cases were non-fraud related.

Lying on the forms is a misdemeanor punishable by up to 364 days in jail, according to the Lewiston Police Department, which has issued four summonses and is pursuing eight more.

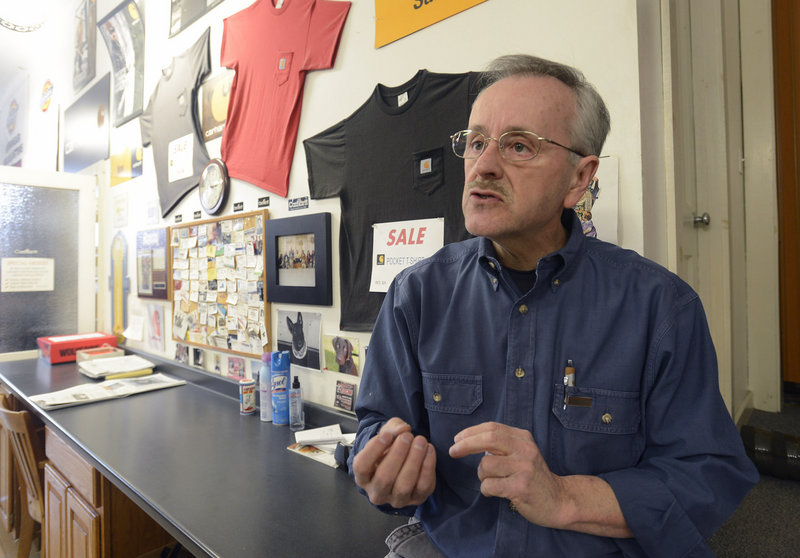

Paul Poliquin, a 59-year-old former Lewiston city councilor who owns a clothing and shoe store on Lisbon Street, said he will wait to see if the mayor’s efforts bear fruit in the form of convictions.

Poliquin, who last served on the council in 1995, said he believes Lewiston has outgrown its reputation as a welfare hub.

“I’m willing to give the mayor the benefit of the doubt,” Poliquin said. “I want to see it followed through.”

LaCourse, meanwhile, has nearly run out of options.

She has applied and been rejected for social security disability in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, and is now attempting to obtain benefits in Maine.

Interviewed at her Lewiston apartment, LaCourse said she is resigned to living with interminable back pain caused, she said, by injuries sustained as a child and later when she worked as a construction flagger.

LaCourse, who has three sons that she sees infrequently, tries not to despair. She was last employed in 2009 at a convenience store in Yarmouth, she said, but re-injured herself when she slipped and fell.

When her situation is overwhelming and dark thoughts creep in, she thinks of her sons.

“What would they say if I quit?”

Staff Writer Matt Byrne can be contacted at: 791-6303 or at: mbyrne@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story