Phil Bowler has a simple, straightforward question for Maine’s Office of the Attorney General.

“Why the hell won’t they give me the file on a 60-year-old murder case?” Bowler, 75, asked last week after going toe-to-toe with Deputy Attorney General William Stokes in Kennebec County Superior Court. “What the hell is the big secret?”

In all likelihood, there isn’t one. Still, as Freedom of Access Act requests go, this case is one for the ages.

It has what this newspaper once called a “New York City socialite” who disappeared without a trace from Monhegan Island in the summer of 1953 – that is until three weeks later, when the Coast Guard pulled her lifeless body from the Atlantic Ocean some 50 miles off Portland Head.

It has not one, but two famous Maine artists and enough rumor and gossip to span 60 years, four months and 22 days (but who’s counting?).

It also has a fundamental question regarding the public’s right to know: At what point should a cold murder investigation – in this case a 518-page file chock full of details about the tragic demise of one Sally Maynard Moran – no longer be kept secret?

“I’ve got a lot of arrows pointing at a lot of people,” said Bowler, whose long white hair and beard suggest a man too busy finding stuff out to waste time on a shave and a haircut. “I told Stokes if I can look at that file, I’ll be able to tell within two days who did it.”

Even without knowing what’s inside?

“I don’t care,” replied Bowler. “Trust me.”

EXIT MARRIAGE, ENTER MONHEGAN

A little history …

Sally Moran, 49, was a close acquaintance of the renowned artist Rockwell Kent, who lived and worked on Monhegan at various times throughout the first half of the 20th century. Thus, when Sally’s marriage to the wealthy advertising executive Daniel E. Moran fell apart and she lost her New York City apartment in 1953, Kent and his third wife, also named Sally, invited her to spend the summer in a cottage they owned on Monhegan.

The Kents’ daughter and her two children had joined Moran there by the evening of July 9, when Moran went for a pre-dinner walk along the island’s majestic cliffs and never returned.

“Monhegan Search for Guest Fails,” reported the Portland Press Herald three days later, after an exhaustive search of the island and the waters around it turned up nothing.

Three weeks later, however, fishermen in the Gulf of Maine came across Moran’s body and summoned the Coast Guard Cutter Acushnet, which transported the corpse to Rockland for an autopsy.

The results, inexplicably not released until that October, showed a skull fracture caused by blunt-force trauma, a broken right arm and no other injuries that might have indicated a fall from the cliffs to the rocks and surf below. Nor was there any indication of drowning.

“I have a feeling someone knows more than they have told us,” said then-Lincoln County Attorney J. Blenn Perkins, who by then had been joined in his investigation by Attorney General Alexander A. LeFleur.

“This case will remain a live entry in my files and in those of the attorney general,” promised Perkins. “We are not going to give up despite all of the complexities of the case, some of which are exasperatingly baffling. It could be quite an extended investigation but we intend to keep trying for a break.”

GRANDNIECE GETS INVOLVED

That break, alas, never came. And as the decades passed, the voluminous witness statements and other investigative material gathered dust at the Attorney General’s Office in Augusta.

Seven years ago, Stokes got a call from Martha Wolfe of Winchester, Va., Sally Moran’s grandniece. Born two years after Moran’s death, she’d long heard about the case from relatives in nearby northeastern Kentucky (where Moran is now buried) and wanted to know if the Maine AG’s office could enlighten her more.

Stokes, who routinely briefs victims’ families on the status of murder investigations, sent her a copy of the whole file.

Enter Phil Bowler, a retired engineer for IBM who over the years has traveled eight times from his home in Burlington, Vt., to vacation on Monhegan, which is about 10 miles off Port Clyde. During his most recent visit, last summer, he caught wind of the story of Sally Moran.

“I research things,” said Bowler, who proudly boasts that he’s visited all seven continents (including five days in Antarctica), 71 countries and every one of the 3,143 counties in the United States since his retirement 12 years ago.

In particular, Bowler likes to research artists, which is what led him to Rockwell Kent, which is what led him to Sally Moran.

The more he dug into the case – he even went to Moran’s gravesite in Louisa, Ky., this fall – the more Bowler wanted to know.

He learned from Kent’s letters that Moran, a model, was one of Kent’s many mistresses. And that when her body arrived home for burial in August of 1953, according to a far-from-substantiated family legend, her head was alleged to be missing.

He learned of two mysterious men who were seen walking around the island the night Moran disappeared. He also learned of an Episcopal minister who, on the same night, heard a woman hollering, “Get your hands off me!” in the vicinity of where Moran went for her walk.

He even learned, from Deputy Attorney General Stokes, that grandniece Martha Wolfe had in her possession the same file that Stokes politely refused to give Bowler. So Bowler called Wolfe a few weeks ago and was, shall we say, rebuffed.

“I don’t think it’s any of his business,” Wolfe said in an interview last week. “And you can quote me on that.”

AG CITES LEGAL ODDITY

Ah, but Bowler believes that after more than six decades, it’s everyone’s business.

Appearing with Stokes before Superior Court Justice Michaela Murphy on Monday, Bowler argued that the state can’t have it both ways: If the Attorney General’s Office is willing to turn the case file over to a Moran relative (who had yet to be born in 1953), then a curious citizen like Bowler should receive “equal protection under the law.”

Stokes countered that he simply can’t: In an odd twist of Maine law, any investigative file produced before 1995 is subject to an old statute that prohibits any and all public release of the file’s contents. (Files produced more recently can be withheld only if the state can prove that releasing them would impair the investigation or cause one of a variety of other harms.)

Stokes conceded that Maine, in effect, now has competing standards for determining what can and cannot be released. Nevertheless, he told the judge, “I don’t think I have the authority to ignore what the Legislature wanted to do.”

As for releasing the file to Moran’s family, Stokes argued, it all comes down to how the state defines “confidential.”

“ ‘Confidential’ means not in the public record,” Stokes told the court. “It does not mean we cannot share intelligence or other investigative material (with a victim’s family).”

Justice Murphy has yet to decide whether Bowler is entitled to see the file. But if she thinks he’s the only person on Earth who’s still wondering what happened to Sally Moran, she might want to think again.

THE MYSTERY CONTINUES

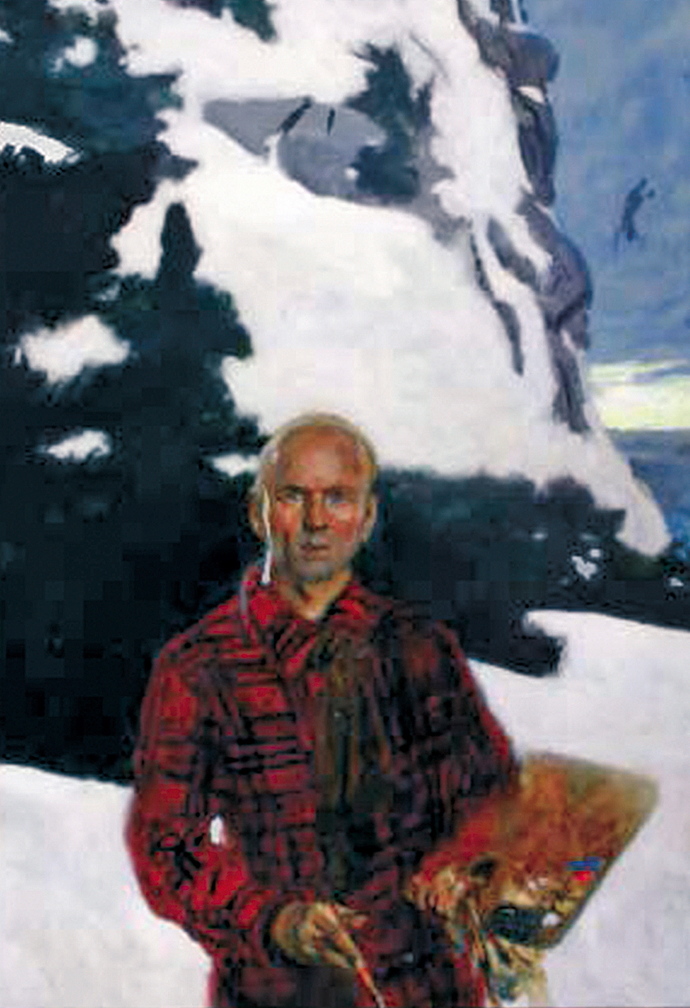

Earlier this year, the artist Jamie Wyeth, an expert on all things Rockwell Kent, produced a painting titled “Portrait of Rockwell Kent, second in a series of untoward occurrences on Monhegan Island.”

It shows Kent standing on a snow-covered Monhegan Island with brush and palette in hand. Far in the background, the shadowy image of a woman can be seen falling from a towering cliff.

Contacted last week, Wyeth said the painting is a nod to Monhegan Island lore, not an insinuation that Kent, who lived until 1971 but never returned to Monhegan after 1953, had anything to do with Moran’s death.

“I knew he wasn’t there at the time” Moran disappeared, said Wyeth, noting that the painting is simply the second in a series of “untoward events that have occurred on Monhegan over the years and this, of course, is one of them.”

Still, Wyeth added, “On this thing lives – and it’s never been resolved what happened to her.”

Which brings us back to that dusty old case file.

Grandniece Wolfe, who’s seen every page, said the file left her less convinced that Sally Moran died of foul play and more confident it was an accident. (For the record, she also insists all that business about a missing head is “absolutely bogus!”)

Stokes, who had the file tucked tantalizingly in his briefcase even as he stood alongside Bowler in court last week, said that even if the court orders him to turn it over, “I don’t think (Bowler) is going to find what he’s looking for.”

“Do I personally get heartburn over this? No, I don’t,” said Stokes.

And Bowler?

He’s feeling underappreciated. If he had his way, the Attorney General’s Office would throw open every one of its 54 unsolved homicides going back 20 years or more (Sally Moran isn’t even on the list) and see what shakes loose.

“They ain’t solved it and they probably ain’t gonna,” Bowler said. “They should be using the public as their ally rather than their adversary.”

Case (not quite) closed.

Columnist Bill Nemitz can be contacted at 791-6323 or at:

bnemitz@pressherald.com

Twitter: @billnemitz

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story