The icy moon Europa squirts water like a squishy bath toy when it’s kneaded by Jupiter’s gravity — and the Hubble Space Telescope has caught it in the act.

The data captured by Hubble depict two huge geysers of water vapor spewing out of the moon, probably from cracks near its south pole. At 124 miles high, the geysers were tall enough to reach from Los Angeles to San Diego.

The discovery, described Thursday in the journal Science, shows that Europa is still geophysically active and could hold an environment friendly to life.

“It’s exciting,” said Lorenz Roth, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio and one of the lead authors of the study, which was presented at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

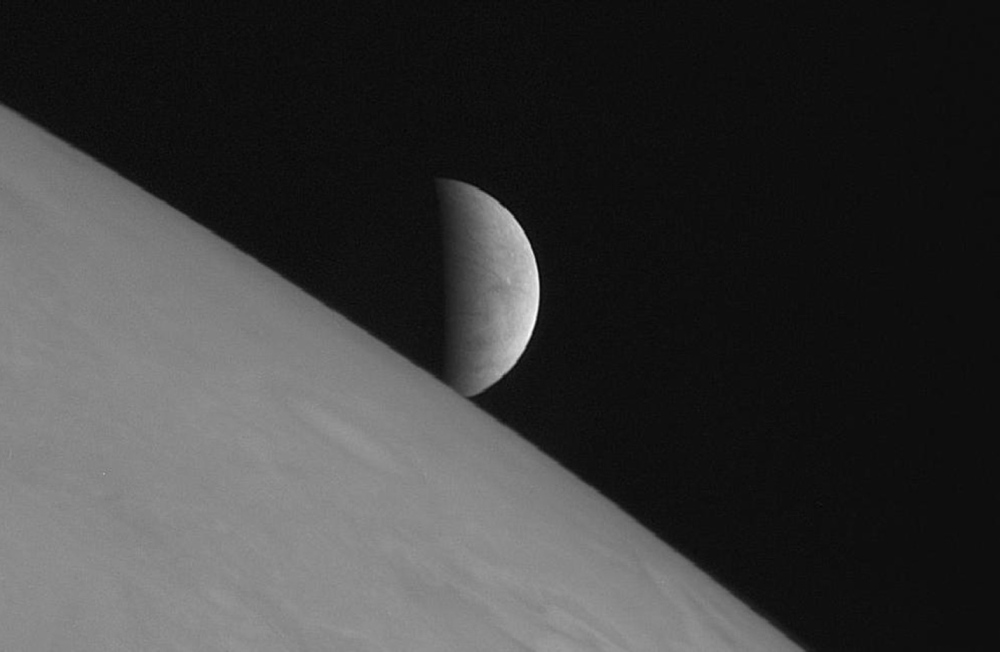

Europa isn’t the only squirty moon in our solar system: Saturn’s moon Enceladus has been caught spraying water from its south pole out of four parallel fractures, a formation that scientists have dubbed “tiger stripes.”

These pretty plumes are the result of tidal forces. Just as our moon’s gravity squeezes and stretches the Earth a bit, causing the oceans to rise and fall, Saturn’s massive gravitational pull squeezes and stretches Enceladus. That causes cracks on its icy surface to open and allows water to escape, feeding the planet’s diffuse E ring.

Scientists have long wondered whether Jupiter was doing something similar to Europa.

Scientists figured that some geophysical processes must be going on that are constantly renewing the surface. But over several decades, researchers repeatedly failed to catch the moon in action, said Robert Pappalardo, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who was not involved in the study.

When the Voyager spacecraft flew by Europa in 1979, it caught a tiny blip on the moon’s edge that experts thought might be a plume, but they couldn’t confirm their hunch. More than a decade later, the Galileo spacecraft saw a potential plume of its own. But this turned out to be digital residue, traces of a previous image, Pappalardo said.

Even Hubble had trouble seeing such plumes until space shuttle astronauts fixed one of its cameras in 2009. Looking for water vapor in the ultraviolet wavelengths of light still tests the limits of Hubble’s abilities, scientists said.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.