GORHAM — A low fire was burning in the Jotul F45 Greenville, but something was missing: smoke.

This new wood stove in the research and development lab here at Jotul North America was venting into an uncapped metal flue, allowing a visible check of just how clean a modern stove can be.

Using seasoned hardwood, the F45 Greenville can burn up to eight hours and heat a 1,600-square-foot house, but send out only 2.31 grams per hour of fine-particle pollution. That’s less than a third of the maximum emissions allowed by the federal government for similar stoves, making it one of the cleanest-burning, mass-produced stoves on the market.

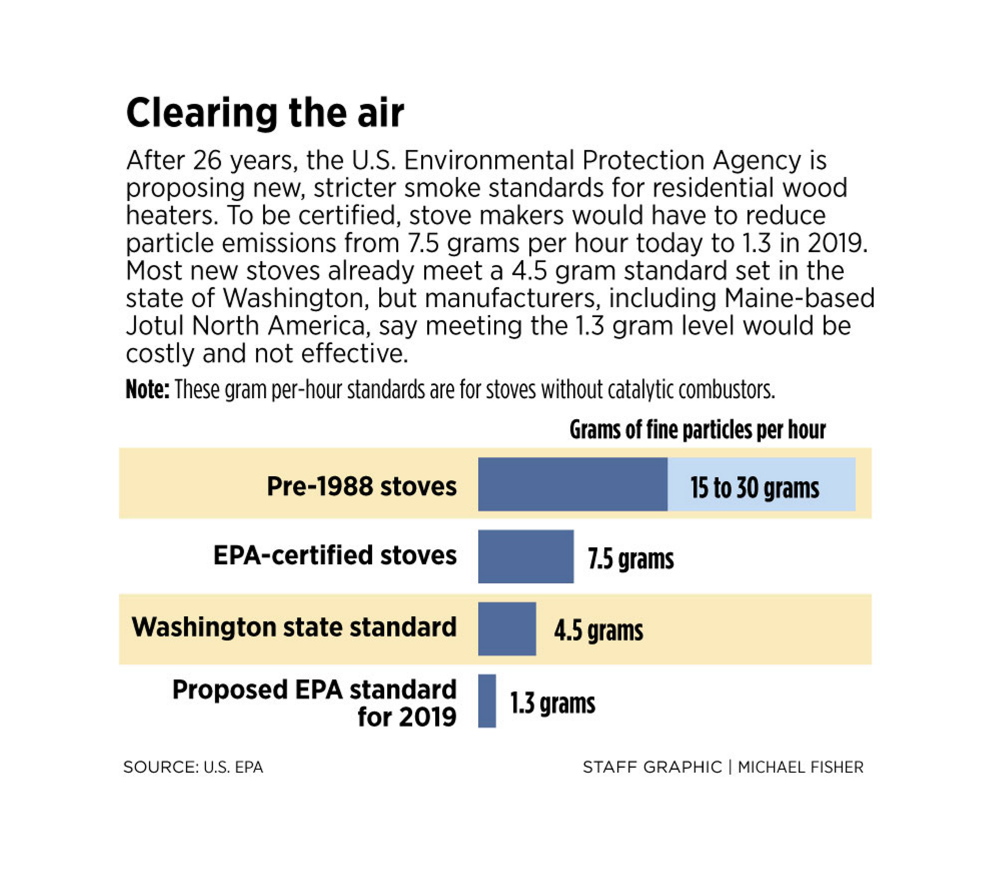

But the government says that’s not good enough. Twenty-six years have passed since the Environmental Protection Agency set emission standards for wood heaters. This winter, the agency is putting the final touches on a far-reaching and controversial update. It would require wood-stove makers to slash particulate emissions to 1.3 grams per hour in 2019.

Some stove makers say this is the wrong approach. Jotul estimates that it will cost nearly $1 million to re-engineer its stoves to meet the 2019 standards and could drive up the cost of a stove by 25 percent. The fix will mean adding catalytic combustion chambers. That technology can reduce emissions, but Jotul says such burners could make it harder for owners to maintain their stoves.

Jotul also points out that there are at least 7 million older-technology stoves kicking around the country, while retailers sold fewer than 74,000 new units last year. A well-built wood stove lasts for generations. So even if the federal government doubles down on the regulations, switching out all the old-style stoves with cleaner models will take decades.

“It doesn’t matter whether we get to zero grams per hour until we get the dirty stoves out of circulation,” said Bret Watson, president of Jotul North America.

Watson has another solution: a wood stove change-out program. Last summer, dealers offered $300 credits to people who exchanged their old stove for a new Jotul, which sells for between $1,000 and $3,000. Buyers also got a $300 federal rebate on top of Jotul’s credit.

The program was the nation’s first stove change-out led by a manufacturer. It captured 1,406 old stoves, 146 of them in Maine.

The promotion was so successful that Jotul plans to do it again next summer. The federal funds will expire, but a $250 Efficiency Maine rebate for efficient wood stoves will help.

The program has won the endorsement of the Northeast chapter of the American Lung Association, which received $10 for every old stove turned in. The group supports stricter emissions standards, but agrees with Jotul that change-outs hold greater promise for improving air quality in the near term.

The new EPA standards also will cover outdoor wood boilers, furnaces and masonry heaters. The draft rules are expected to be issued soon, followed by a 90-day comment period. Public hearings could be held next spring in Boston and Seattle.

It’s clear the agency is under pressure to enact the most stringent standards possible.

Seven states that include Massachusetts and Connecticut – but not Maine – have filed a notice to sue the EPA for failing to revise its outdated air pollution standards for residential wood heat. Their top concern is outdoor wood boilers, but they are also concerned about wood stoves.

Advocacy groups also are weighing in.

Jotul’s program is commendable, according to the Alliance for Green Heat, a Maryland-based group that promotes clean wood stoves, but the impact of change-out programs is overestimated.

Change-outs typically underperform when they are open to everyone and don’t target the worst polluters, according to John Ackerly, the group’s president. And in areas where other residents can still install old secondhand stoves, the clean-air benefits of the new stoves are canceled out.

Most stove change-outs also fail to get at the other half of the problem – burning wet, unseasoned wood and setting low, smoldering fires. Some experts now wonder if a $150 rebate to build a wood shed to keep wood dry could improve air quality as much as handing out $1,000 for a new stove, Ackerly said.

TRADITION VERSUS AIR QUALITY

The outcome of this debate is important to Maine.

Heating with wood is a cherished and thrifty tradition that has been making a comeback in Maine. A greater percentage of homes use wood as their primary heat source – 14 percent – than any state other than Vermont, according to U.S. Census figures. An estimated 50 percent of Maine homes also use wood as a supplemental heat source.

The trend is good for cutting expensive oil bills, but not for air quality. It is an inconvenient truth, but typical wood stoves churn out far more of the pollution that aggravates asthma and other respiratory conditions than the oil and gas heating systems they’re meant to supplement or replace.

Americans began buying wood stoves in the mid-1970s, after high oil prices triggered the first “energy crisis.” Some of these stoves belched out more than 40 grams per hour of fine particles, as much smoke as a vintage diesel bus.

Responding to public health complaints, the EPA set emission standards in 1988 for new, non-catalytic stoves at 7.5 grams per hour. In 1995, Washington state enacted its own standard of 4.5 grams, which has become a de facto benchmark for new wood stoves sold today in the United States. Most pellet stoves, which have become popular in Maine in recent years, also come in below the Washington state standard.

A STRICTER STANDARD HAS LIMITS

The stove line sold by Jotul North America averages 3.7 grams/hour. The factory here is Maine’s only wood stove manufacturer. It is the subsidiary of Norwegian-based Jotul Group, the iconic Scandinavian stove maker. The Gorham plant employs 75 people who assemble and fabricate units with parts shipped from Norway. Product developers here also designs stoves, such as the F45 Greenville.

The factory is a busy place now. Workers are striving to fill a backlog of orders. On a recent visit, the assembly line was putting together the Maine-designed F-55 Carrabassett, a large, steel-and-cast-iron stove with a heating capacity of up to 2,500 square feet. It retails for roughly $2,500.

The F-55 Carrabassett is EPA-certified at 3.5 grams/hour. To reduce emissions much further, Jotul says it would have to redesign the stove and fit it with a catalytic combustion chamber, which would make what’s already an expensive stove less affordable.

“The real task is to give people in rural Maine incentives to replace their stoves,” said Watson, the Jotul president.

The further irony, Jotul says, is that hitting the 1.3 gram/hour EPA target won’t necessarily translate into cleaner air. The current EPA test method uses dry, Douglas fir lumber. In the real world, people burn firewood that may be left out in the rain and snow and is not fully seasoned. Wet, recently cut wood burns less efficiently and gives off more smoke.

OLDER STOVES THE MAIN CULPRIT

The EPA declined to talk about its testing program or the proposed performance standards for wood heaters, noting that the matter is under review. A staffer did say EPA has conducted two years of outreach and received important feedback, and that public comments will be welcomed when the proposal is formally issued.

Some of that information has come from the Hearth, Patio & Barbecue Association, which represents many stove makers. It commissioned a study that found meeting standards below 2.5 grams/hour wasn’t cost-effective, in terms of the extra amount of particle pollution removed from the air.

Jotul also has been trying to make this case with the help of Maine’s congressional delegation, notably Sen. Susan Collins. Behind the scenes, Jotul and a handful of stove makers, including HearthStone of Morrisville, Vt., and Regency of Vancouver, British Columbia, are engaged with EPA staffers and with the Office of Management and Budget, which has been conducting a cost-benefit review.

“What is missing,” said David Kuhfahl, president of HearthStone Quality Home Heating Products Inc., “is that the EPA has allowed inexpensive, dirty products to continue on the market all these years. The biggest opportunity to clean up the air quality is to replace the majority of stoves in use today that do not meet the realistic combustion quality of the stoves we have developed.”

Kuhfahl also said he fears consumers will reject stoves that require technical maintenance and expensive repairs.

“The reality is that the wood stove as we know it would go away,” he said.

Jotul also has been conducting a back-and-forth with EPA staffers, including Gil Wood, the lead official on the new regulations. In an email exchange last month, Wood said he agreed with the merits of changing out old wood stoves.

“The hurdle is, where does the U.S. get the billions of dollars to replace the millions of old, dirty (pre-EPA regulations) wood stoves, even though the monetized health benefits far exceed the costs?” Wood replied in his email.

CHANGE-OUT PROGRAMS LACK FUNDS

In other states, change-out programs have been launched with combinations of government and private funds. One effort in southern New Hampshire used $250,000 from federal fines against commercial polluters. It offered extra money for low-income residents. Western Massachusetts had $800,000 this year for a second-round program funded largely from EPA fines on coal-burning plants.

Change-out programs often target populated areas in river valleys or near mountain ranges, where wood smoke settles on calm, cold nights. Those conditions exist in several Maine communities.

“In this part of the country, change-out programs are the best way to reduce particle pollution,” said Ed Miller, the lung association’s senior vice president for policy.

Maine has a wood-stove change-out law that’s similar to the program in southern New Hampshire. The problem is, there’s no money to fund it.

Monitoring stations run by the Maine Department of Environmental Protection show that the state’s air quality meets federal particulate standards, and has been improving. But problem areas do exist. The state did a special wood-smoke study a few years ago in Greenville, but the proximity of Moosehead Lake appears to have diluted the results. Now the DEP is thinking about a new study in Bethel, where some residents are complaining.

BALANCED APPROACH FAVORED

“Violating the standards and causing a nuisance are two different things,” said Marc Cone, director of the DEP’s air quality bureau.

Cone said the DEP’s interest is balancing air quality with affordable heat. He expects the state to weigh in on the EPA proposal when it’s released.

“We want to see a continued reduction in what stoves put out,” he said. “However, we don’t want stoves to cost twice as much.”

A similar point of view is being expressed by U.S. Rep. Mike Michaud, who represents Maine’s sprawling and rural 2nd Congressional District. It has the highest concentration of wood and pellet burning of any district in the country, according to the Alliance on Green Heat.

“As with any other source of energy,” Michaud said in a statement, “regulations should offer a balanced approach and keep pace with modern technology. I would encourage the EPA to ensure that any new standards protect public health and the environment, without unnecessarily burdening manufacturers or making wood stoves unaffordable for consumers.”

Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or at:

tturkel@pressherald.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.