Two major oil companies are exploring potential drilling sites in waters off Nova Scotia, in an undertaking that ultimately could generate opportunities for Maine businesses but pose a threat to the state’s fisheries.

Nova Scotia’s government has granted Canadian subsidiaries of Shell Oil Co. and BP Plc. rights to explore thousands of square miles of ocean floor in search of commercially viable oil deposits. Each company has committed to about $1 billion Canadian in surveying costs over the next several years.

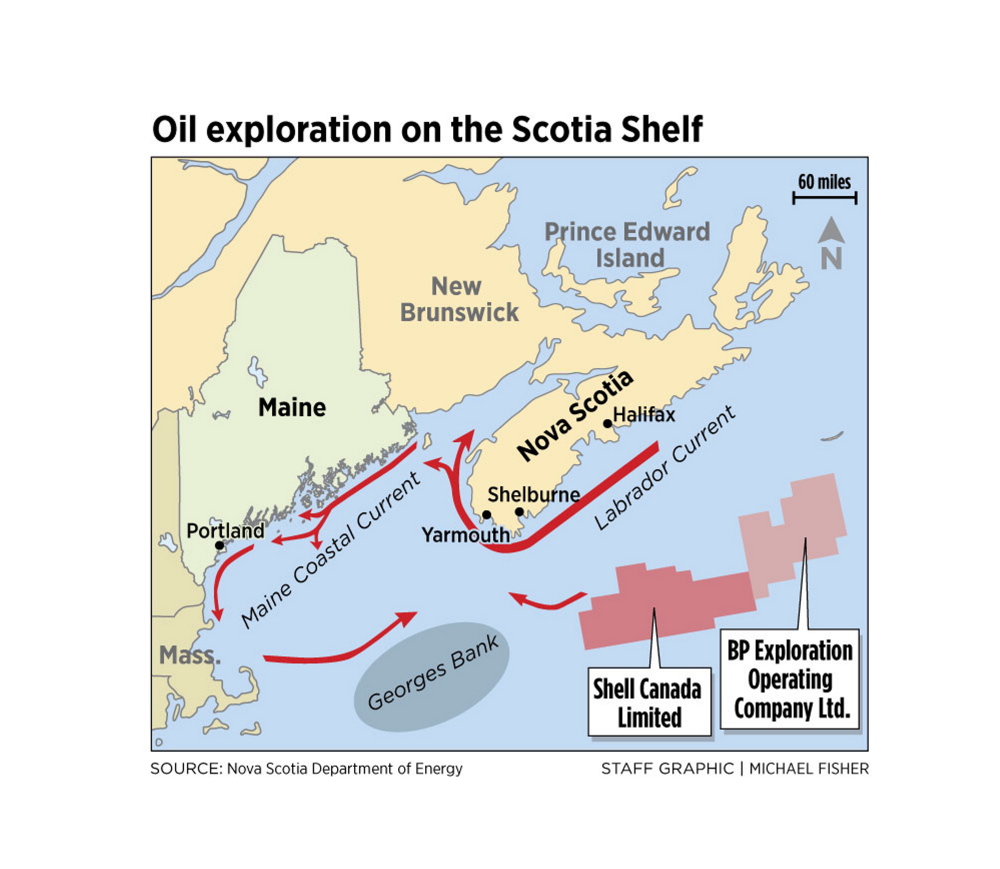

The exploration zone, which extends east from an area about 100 miles southeast of Nova Scotia, is far from the Maine coast – nearly 400 miles east of Portland. But drilling ultimately could occur within 50 miles of Georges Bank, a productive fishing ground that’s shared by fishermen from Nova Scotia and New England.

And while the ocean east of Nova Scotia seems far away to most Mainers, currents that act like a “conveyor belt” would bring oil from a major spill into the Gulf of Maine and down along the Maine coast, said Peter Shelley, senior counsel for the Boston-based Conservation Law Foundation.

“Anything that happens on the Scotian Shelf will show up in the chemistry of the Gulf of Maine,” he said.

Shell has completed a seismic study and plans to begin drilling as many as seven exploratory wells next year. This spring, BP will begin a two-year seismic survey of a 5,000-square-mile area off the coast of Nova Scotia.

Nova Scotia’s government is pushing for the projects because it stands to receive several billion dollars in royalties if oil is found in quantities similar to those found in oil fields off Newfoundland.

The demand for support services such as repairing oil rigs and vessels would be so large that the entire region would benefit, including Maine, said Andrew Younger, Nova Scotia’s minister of energy.

There would be work for Maine contractors, he said, and equipment from Texas could come to Portland by rail and then be put on ships bound for the oil fields.

“The reality is, there are always services Nova Scotia won’t be able to provide,” Younger said. “If you get into full-on development, that is when you will see spinoff in the region.”

He said the ferry service between Portland and Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, that’s scheduled to start in May would provide a key transportation link for the project and foster closer business relationships.

Peter Vigue, chairman and CEO of Pittsfield-based Cianbro Corp., which has industrial facilities in Brewer and on Portland’s waterfront, said he is keeping an eye on energy products in both Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. He noted that Cianbro already has a relationship with Shell.

In 2007, Cianbro was hired by Motiva Enterprises – a joint venture between Shell Oil Co. and Saudi Aramco – to build 51 modules for a multibillion-dollar refinery expansion project in Port Arthur, Texas. That project employed about 500 people.

Vigue said it would be six to eight years before the Nova Scotia projects would lead to productive oil fields.

“We are monitoring and staying in touch and looking for opportunities to build our relationship,” he said.

Younger said that environmental protection is the priority for the provincial government, and that it reviewed all of its regulations and safety systems after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010.

That spill, the largest accidental marine oil spill ever in the petroleum industry, occurred when a deep-water oil rig exploded and oil flowed from a sea floor gusher for 87 days, discharging nearly 5 million barrels before the well was sealed.

Younger said the province’s regulations are much more stringent than those in the Gulf of Mexico, and environmentalists and fishermen in New England don’t need to worry about the impact of oil spills because the Gulf Stream – which moves northeast – would carry oil away from the Gulf of Maine.

“That would be the strongest current we have,” he said. “It pulls north rather than south.”

But David Townsend, an oceanography professor in the University of Maine’s School of Marine Sciences, said that’s simply not true.

Townsend, who examined a map of the exploration area, said the Labrador Current, a cold-water current that moves southwest, is the predominant current through the area. “That (current) is flowing right over those drill sites,” he said.

Townsend said the current enters the Gulf of Maine through the Northeast Channel, a deep fissure between Georges Bank and Browns Bank, two elevated areas of the sea floor. The flow is much stronger in some years than in others because of changes in weather patterns over the North Atlantic, he said.

Because of circular currents in the Gulf of Maine, which is much like an inland sea, a major spill could cause highly diluted trace oil to reach coastal waters in Maine, he said.

The U.S. government has no jurisdiction over the exploration projects because they are in Canadian waters, but both the U.S. and Canada have imposed a moratorium on oil drilling on Georges Bank.

Patricia Fiorelli, spokeswoman for the New England Fisheries Management Council, the federal entity that manages fisheries in the region, said the staff in the council’s headquarters in Gloucester, Mass., was not aware of the oil exploration off Nova Scotia.

“Details have not come to the council’s attention yet, but we will be paying attention to it in the future and trying to figure out whether we are going to become involved in some way,” she said.

Tom Bell can be contacted at 791-6369 or at:

tbell@pressherald.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.