Lobstermen’s efforts to mark egg-bearing female lobsters with a V-notch on their tail have been on the decline since 2008, which could put pressure on the future health of the state’s most lucrative fishery, state officials said.

If a female lobster is caught while carrying eggs, a V-notch tool or knife is used to remove a very small, triangular portion of the tail flipper. That lobster is then returned to the water. V-notching began in Maine in 1917 and has been mandatory since 2002, but the practice is very difficult to enforce, officials said.

By throwing back the V-notched female lobsters, it allows them to grow larger and reproduce in future years. A V-notch lasts for about two molts or roughly two to three years – depending on the size of the cut – and acts as a signal for the next harvester that catches the lobster that it should be returned to the water to keep the reproductive cycle going, according to Kathleen Reardon, lobster scientist for Maine’s Department of Marine Resources.

“It creates a buffer for sustainability for the population,” Reardon said. “Because of V-notching, we’re protecting the reproduction cycle. It’s the only mechanism to return a legal sized lobster back to the water to reproduce.”

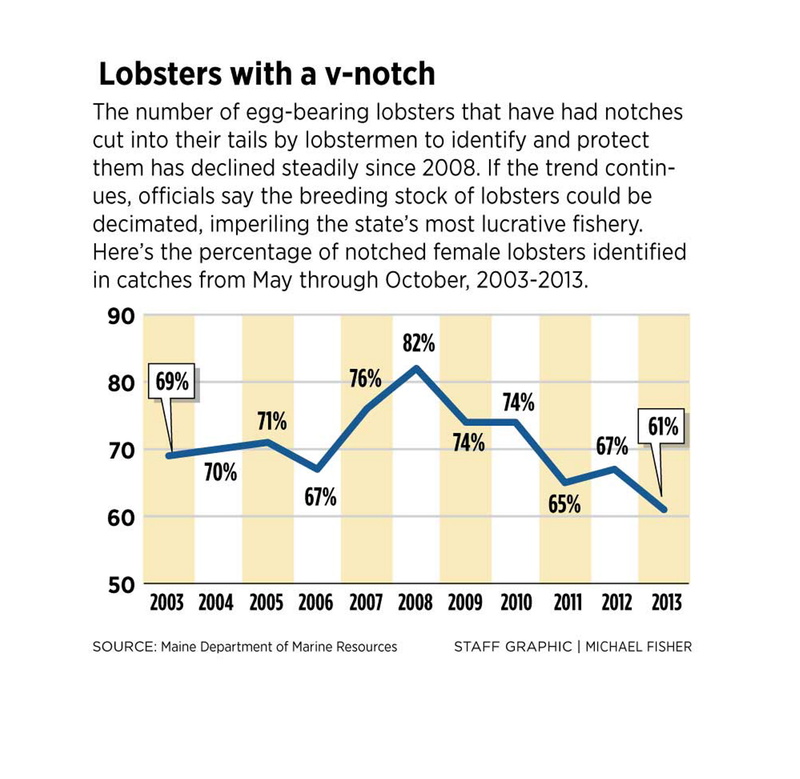

The percentage of egg-bearing lobsters with a V-notch peaked in 2008, when 82 percent of those sampled statewide were marked. That average has declined nearly every year and dropped to 61 percent in 2013. Last year, the prevalence of V-notching was higher in Zone F, which had a rate of 70 percent. The compliance rate hit a low of 50 percent in Zone A.

Zone F runs from the Presumpscott River to Small Point, while Zone A is in the east from Schoodic Point to the Canadian border.

“Previous generations of lobstermen made financial sacrifices on your behalf by V-notching lobsters, essentially putting some landings in the bank for the future,” Patrice McCarron, executive director of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association, said in the trade group’s April newsletter. “If lobstermen continue to choose not to V-notch, the lobster resource could be headed for a serious decline.”

According to projections from the DMR, the lobster fishery could collapse within 10 or 20 years if lobstermen stopped the practice of V-notching lobsters and throwing the egg-bearing females back into the water, Reardon said. If lobstermen simply cut in half their participation from the 2007-2011 levels, the fishery would still collapse, but the decline would take about 30 years, she said.

Such forecasts, however, aren’t perfect and the lobster population could be affected by several other factors such as water temperature and disease. Also, any drop in population would be from historically high levels, state officials said.

Still, the decrease in the percentage of V-notched egg-bearing females is troublesome as it indicates decreasing participation by fishermen at a time of smaller settlements of juvenile lobster, Reardon said.

According to an annual survey of young lobsters in 11 locations in the Gulf of Maine, juvenile population settlements have fallen by more than half since 2007, according to research by the University of Maine. The American Lobster Settlement Index is used as a predictor of trends in the fishery.

The two issues contribute to the cautious outlook for the state’s lobster industry, state officials said.

“We’ve seen a meteoric increase in landings since 1980, when were at about 20 million pounds. Now, we’re at 125 million pounds. We can’t expect to be at record levels forever,” said Carl Wilson, the DMR’s top lobster biologist. “These are extraordinary times. The key is how this fishery reacts to change. The decline in V-notching is not a positive trend.”

Wilson cautioned that V-notching is just one factor affecting the lobster fishery.

“We can’t attribute all the success of the fishery to V-notching, nor can we say that it gets all the blame for any potential decline. By not V-notching, that’s taking a tool out of the toolbox that’s been beneficial in the past,” Wilson said. “By participating in V-notching, you are participating in the future. We need to double down on the investment in the future.”

The decline in the V-notch participation rate was observed as part of the state’s sea sampling program. That program, which started in 1985, sends observers to measure the catch on boats from May to November. There are three trips a month in each of the state’s seven harvesting zones. The observers measure every lobster caught, including the immature lobsters that get thrown back.

“There’s a number of potential reasons for the decline. Attitudes may be changing. Fishermen may be doing their own stock assessment and the attitude is that there’s enough V-notches on the bottom,” Reardon said.

Another factor that may be deterring lobstermen from V-notching include the huge volume of lobsters being harvested and the time crunch, she said.

Last year, nearly 126 million pounds of lobster valued at $364.5 million was harvested in the state. That catch was down slightly from the 127.2 million pounds caught in 2012, when the value of the harvest totaled $341.8 million.

Wilson said that due to the boom in the lobster population, the absolute number of V-notched lobsters may be the same or higher than in the past. On a percentage basis, however, there’s fewer V-notched lobsters, he said.

“There are so many unknowns and variables. I don’t think it’s a big deal. There’s a large portion of large, female lobsters already notched,” said Brendan Ready, co-owner of Ready Seafood in Portland. “I don’t think it will affect anything on the sustainability of the fishery. There’s no predator to consume these (notched) females.”

Maine has long-prided itself on its conservation efforts. Massachusetts fishermen notch lobster, but at a lower participation rate than Maine, Wilson said. The Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries did not return calls seeking comment.

“Back in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, there was an evolution of the fishery from a ‘take anything’ fishery to a modern fishery based on conservation. Maine fishermen were participating in V-notching and landings were stable,” Wilson said. “Then, with declining predators and increasing water temperatures, we saw a boom. Rather than saying we know why – we can at least say the conservation efforts allows the resource to double, and then double again when favorable conditions were present.”

“I notch. A lot of fishermen do. It’s a close-knit community. Everyone knows who notches and who doesn’t. Some people of the younger generation don’t take the time and effort to do it. You’ll find that those in their 40s or older do. They see notching as protecting the future,” said Rocky Alley, a lobsterman in Jonesport and president of the Maine Lobstermen’s Union.

Jessica Hall may be reached at 791-6316 or at:

jhall@pressherald.com

Twitter: @JessicaHallPPH

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story