In 1977, Gov. James B. Longley broke a 157-year-old tradition. He appointed an attorney, not a sitting judge, to be chief justice of the Maine Supreme Judicial Court.

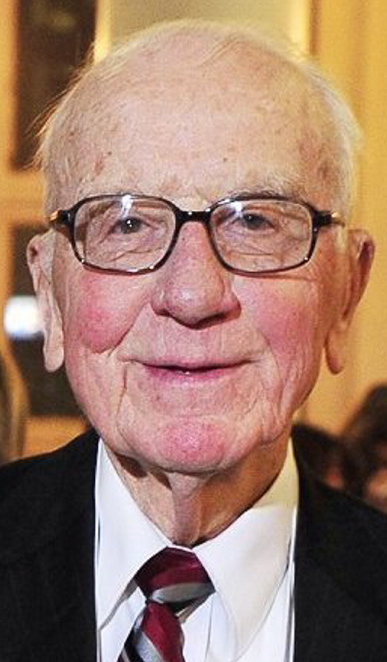

Yet the appointment of Vincent Lee McKusick was well-received, if not expected.

“It was a no-risk appointment,” said another former chief justice, Daniel Wathen, who served 10 years with McKusick on the court. “Everyone recognized that he was just an outstanding lawyer, an outstanding intellect.”

McKusick died Wednesday at Legacy Memory Care in Falmouth. He was 93.

From humble beginnings, he went on to lead a storied life that intersected with two of the nation’s legendary legal minds and included a 14-month assignment to the Manhattan Project. After being recruited by an influential attorney with Maine ties, the call of his home state pulled him from the orbit of Washington, D.C.

McKusick became known as one of Maine’s best and brightest law practitioners, and he quickly vaulted to the Supreme Judicial Court in 1977, serving as its chief justice until his retirement in 1992.

“He was recognized throughout Maine as being the smartest lawyer in town, but the thing that was really outstanding about him is he was unfailingly kind,” Wathen said. “I never saw him during those 10 years show any irritation with me, or his colleagues, or the lawyers who came before us. That’s not an easy thing to do when you’re seven people working together, day in day out.”

HARVARD TO WASHINGTON TO MAINE

McKusick was born in Parkman on Oct. 21, 1921, the son of Carroll and Ethel McKusick, both former educators who owned a dairy farm. His twin, Victor McKusick, became a renowned geneticist before dying in 2008 at the age of 86.

The twins attended grammar school in a one-room school house. Their graduating high school class had 28 members. They were co-valedictorians, according to a tribute article published in the Maine Law Review.

Vincent graduated from Bates College in Lewiston before serving in the Army during World War II, when he participated for 14 months in the Manhattan Project, the code name for the research program to develop the atomic bomb. After the war, he earned a master’s degree in 1947 from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

His pursuit of an electrical engineering degree reflected his ambition to work in patents. He enrolled in Harvard Law School to pursue patent law and was later elected president of the Harvard Law Review, a position that broadened his interest to general-practice law while establishing professional relationships that would shape his legal career.

He graduated magna cum laude from Harvard in 1950. Shortly thereafter, he became the law clerk to Chief Judge Learned Hand of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Hand, regarded by some as the greatest jurist of his time, was known as the “10th Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court,” a reference to his national stature in the legal community. Hand later recommended that McKusick serve as clerk for Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter.

McKusick’s blossoming legal resume soon drew the attention of another rising star, this one also from Maine.

Fred C. Scribner Jr. was a Bath native who went on to serve as under secretary of the Treasury in the Eisenhower administration and other positions in the Republican Party. Wathen, the former chief justice, believes Scribner “was heavily engaged in recruiting Vincent to come back to Maine.”

Former Gov. John Baldacci, who worked with McKusick as a member of Congress and later at the same law firm, said Maine had its own gravitational pull – that McKusick had a strong connection to his family and Parkman.

“It meant a lot to him,” Baldacci said. “He also cared about Maine, cared about the reputation of Maine. Even in his office he had pictures and memorabilia from his childhood. He never forgot where he came from.”

McKusick returned in 1952, shortly after marrying Nancy Elizabeth Green.

Said Wathen, “The Maine connection was strong. He came back and he quickly became one of the leading lawyers in Maine for sheer intelligence and knowledge of the law.”

In 1952, McKusick began his career at the Portland law firm of Hutchinson, Pierce, Atwood & Scribner – now known as Pierce Atwood. According to a 1992 tribute in the Maine Law Review written by Scribner, McKusick was originally supposed to join the firm a year earlier, but the clerkship with Frankfurter beckoned. He asked the partners if they could wait a year.

“The question answered itself,” wrote Scribner, who acknowledged that he was happy that McKusick didn’t contract “Potomac Fever.”

“Of course the position would be kept open,” Scribner wrote. “For a Maine firm to have as an associate a lawyer who had clerked for Judge Learned Hand would be a special privilege, but to have a lawyer who had clerked for both Learned Hand and Felix Frankfurter was an almost unbelievable opportunity.”

McKusick became a partner in 1954. He began working with Leonard A. Pierce, a former member of the Harvard Law Review and a former state lawmaker. They focused on utility clients, rate cases and a constitutional matter involving the Maine Turnpike Authority.

In 1977 it was Longley’s turn to call on McKusick. Appointing a chief justice straight from the bar was almost unprecedented.

“It was very traditional that the chief justice in particular would be often the most senior judge of the supreme court,” Wathen said. “There was a rotation system and Vincent was appointed with no prior judicial experience to be chief justice.”

Such an appointment had not happened since the appointment of Chief Justice Prentiss Mellon in 1820. It has remained a rarity.

Baldacci said he only did it once in his eight years as governor – Supreme Court Justice Warren Silver in 2005.

“It doesn’t happen very often, but when it does you get a very special and unique individual,” Baldacci said.

TIRELESS, DEVOTED TO PUBLIC SERVICE

McKusick turned out to be both. In more than 14 years on Maine’s high court, he brought significant improvements in the structure and operation of all courts, many involving volunteer efforts from within the community, such as Maine’s Mediation Program and its Court Appointed Special Advocate Program.

According to Wathen, who joined McKusick on the Maine Supreme Judicial Court in 1982, the chief justice was indefatigable.

“He was just absolutely tireless about working, particularly research writing,” Wathen said. “When we were on the court together, we’d all go out to lunch and he’d want to work through lunch. He’d want to take up administrative matters. Some of us were getting a little tired of that. When you’ve been hearing oral arguments all day, you don’t want to spend lunch wrangling over administrative matters.”

Wathen added, “He just loved it.”

McKusick also appeared to have a love for public service. According to Scribner’s retirement tribute, McKusick took a significant pay cut to join the bench. It didn’t stop him from working. In fact, Scribner recalled a speech that McKusick gave to his law firm extolling the virtues of public service.

McKusick said the firm should stay in touch with the community or risk underserving its clients. If Pierce Atwood restricted its business to large and financially sound corporations and individuals with substantial incomes, it would become “a different firm – one less in touch with the community – and one seen by the public as blind to any professional motivation aside from serving selected clients for large compensation.”

After his retirement from the bench in 1992, the justice rejoined Pierce Atwood, where he continued to serve as counsel. In that time, McKusick received three special master appointments from the U.S. Supreme Court, handling original jurisdiction cases between states.

Jim McKusick, 60, said his father worked until he turned 90.

“He was a wonderful dad. He was always very supportive,” his son said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story