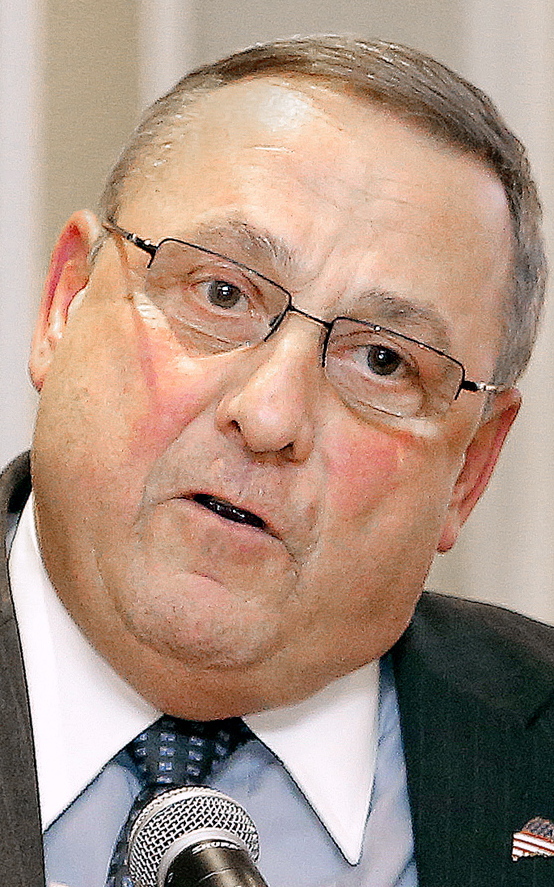

Republican Gov. Paul LePage has an ambitious plan to cut or eliminate Maine’s income tax, a goal that is very likely to clash with Democratic House Speaker Mark Eves’ priority of holding the line on rising property tax rates.

LePage has said getting rid of the income tax will make the state more competitive to attract business investment, jobs and new residents. Details of his plan could be revealed when the governor releases his two-year budget proposal Friday.

Doing away with the tax would eliminate nearly half of the approximately $3 billion in annual revenue that finances state government. And paying for that, or even a significant reduction, would require dramatic cuts in state spending, replacing the lost revenue with increased sales tax collections or a combination of both.

An income tax cut also could mean more reductions in state aid to municipalities, a move certain to be opposed by Eves and Democrats because it would likely lead local governments to raise property tax rates as a way to maintain budgets for road plowing, police and fire protection and other services.

The two leaders’ diverging tax priorities foreshadow a potential slog in negotiations over the state’s two-year budget. And they illustrate long-standing partisan differences over tax policy that have long hindered reforms.

In the end, any cut to the income tax would have a profound effect on Mainers, who could end up seeing more money in their paychecks, while at the same time paying more to keep their homes or to buy goods and services that are currently exempt from the state’s sales tax.

Details of LePage’s tax proposal have been in development for several months, yet closely guarded. Neither officials in the administration’s finance office nor in Maine Revenue Services responded to requests for comment. However, both Republicans and Democrats expect an aggressive plan from the governor, who has claimed a voter mandate following his decisive re-election in November.

“It seems pretty clear to me that the governor wants to go big and bold,” said Matthew Gagnon, CEO of the Maine Heritage Policy Center, a conservative advocacy group. Gagnon, who has met with the governor to discuss the income tax plan, expects the Republican to advance a proposal that quickly reduces the income tax rate, rather than an incremental reduction.

Passing any income tax cut will require support from Eves and the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives. And because Maine’s Constitution requires the state to have a balanced budget, a tax cut must be offset by other savings initiatives or revenue increases – unless lawmakers structure it in such a way that the next Legislature will have to make those choices.

The LePage administration has already indicated that the entire budget proposal will be close to the state’s current $6.3 billion two-year budget. Revenues from the state income tax were $1.41 billion in fiscal year 2014.

Eves said he expects a “substantial income tax bill” from LePage. The proposal, he said, will be thoroughly vetted, but the Democratic leader is not convinced that a sharp reduction in the income tax is the economic panacea touted by Republicans.

“Well, it hasn’t worked so far,” said Eves, referring to a 2011 income tax cut package passed by the Legislature. That tax cut lowered the state’s top income tax rate from 8.5 percent to 7.95 percent and eliminated the tax liability for approximately 70,000 low-income Mainers.

“If you look at the governor’s proposal last time and look at where the Maine economy is right now, we’re still lagging behind New England and the country,” said Eves, noting that the state trails its New England neighbors in wage growth and job creation. “We’re going to look at everything through the lens of job creation and make sure that we’re doing everything that we can to create good-paying jobs in the state. Our tax policy has a lot to do with that.”

LePage has long coveted elimination of the state’s income tax, which he says discourages business investment.

“I think there’s room to eliminate the income tax,” he told WCSH-TV in Portland shortly after his re-election in November. “We have to do that if we have any expectation of being competitive with the big states.”

At $1,070 per person, the Tax Foundation ranked Maine the 14th highest in per capita state and local individual income tax collections. The ranking, however, is based on U.S. Census data in 2010, which are the most recent available but do not reflect Maine’s 2011 income tax cut and realignment of income tax brackets. The average individual tax liability dipped to $1,065 per capita in 2014, but there are no comparative data available from other states.

Six states do not assess individual income taxes, while New Hampshire does so only on investment income. Those states pay for government and services by replacing an income tax with other taxes and income.

For example, Florida allows counties to assess sales taxes to pay for certain infrastructure needs. Alaska, which has neither a sales nor an income tax, has a general fund approximately 90 percent funded by oil and natural gas extraction.

Other states without income tax have a broad sales tax base, meaning fewer items or services are exempt from sales taxes. And in New Hampshire, the absence of a standard state income tax is accompanied by higher property tax bills.

New Hampshire residents pay some of the highest property taxes in the country, according to data from the U.S. Census American Community Survey. In 2010, per capita property tax collections in New Hampshire were $2,463, the fourth highest in the country.

Maine property owners pay between $1,000 and $2,000 in property taxes, with higher rates in coastal towns and southern Maine. The Tax Foundation ranked the state No. 11, or “relatively high,” in per capita property tax collections.

And Mainers have seen the property tax burden grow.

According to the Legislature’s Office of Fiscal and Program Review, Mainers’ per capita spending on property taxes increased from $1,623 in 2008 to $1,987 in 2014. Property taxes represented 4.9 percent of personal income in 2014, compared to 2.6 percent for income taxes.

Maine’s property tax rates are a concern for state and local policymakers, and recent proposals to reduce state funding for local communities have heightened those concerns.

The municipal revenue sharing program, established in 1972, distributes 5 percent of all sales and income tax collection to municipalities to fund local government, hold down property taxes and to counterbalance what municipal officials believe is the state’s disproportionate reliance on property taxes for revenue.

State officials have gradually reduced the revenue sharing since 2008 as a way to balance the state budget. The issue came to a head in 2013 when LePage proposed a two-year elimination of municipal aid as a way to help pay for the 2011 income tax cuts. The Democratic-controlled Legislature and the Republican minority cobbled together an alternative proposal that eased the blow, but did not entirely spare the revenue sharing program.

In the current fiscal year, 60 percent of tax revenues that were supposed to go to municipalities were redirected into the state’s General Fund.

“Instead of sharing, state government has come to treat the revenue sharing program as a magic ATM machine, the withdrawals from which never have to be repaid,” wrote Geoff Herman, the advocacy director for the Maine Municipal Association, the organization representing most of Maine’s cities and towns. Herman’s remarks were written for the December issue of the MMA magazine Maine Townsman, an issue that effectively doubled as an action alert: Revenue sharing, the MMA noted, is on the chopping block.

The governor objected to revenue sharing cuts when he was mayor of Waterville but as governor has called the fund “welfare for towns and cities,” arguing that the state has made tough decisions to decrease spending, so municipalities should, too.

Eves did not provide specifics about his plans to reduce property taxes, suggesting that his main objective is to preserve revenue sharing and to beef up property tax relief programs that were either eliminated or replaced during the last budget.

“There’s common ground on property tax relief, particularly when it’s a focus on providing relief for seniors,” Eves added. “We were able to double the property tax relief credit last session. We’re going to continue to have that focus this time.”

Eves’ defense of municipal revenue sharing and LePage’s anticipated plan to cut it suggests a forthcoming standoff. However, there may be some common ground between the two leaders.

The state currently provides $1.87 billion in annual sales tax exemptions, more than enough to make up for any loss from the projected $1.46 billion in income tax revenue in the current fiscal year.

Eliminating the exemptions to pay for a full income tax cut, or even a significant reduction, has proven politically perilous. Such efforts have crumbled under the pressure from affected interest groups or rejected when politicized for electoral purposes.

In 2010, a tax reform proposal that lowered the state income tax by eliminating sales tax exemptions for goods and services such as ski tickets and car repairs was overturned by a Republican-led ballot measure. In 2013, a similar proposal advanced by a bipartisan group of 11 lawmakers fizzled amid fears of a repeat of 2010.

Later that year, a special commission reviewed sales tax exemptions to determine if some could be eliminated. The panel’s work was doomed from the outset. At one point it floated the idea of eliminating the sales tax on some recreational activities. Republican operatives pounced, saying the Democratic panel wanted to create a “fun tax.”

The committee’s final recommendations went nowhere.

Eves suggested that Democrats and Republicans could agree on removing sales tax exemptions, but said it would require bipartisan leadership.

“You have to create an environment where Democrats and Republicans can trust each other through the whole process,” he said.

Gagnon, the CEO of the Maine Heritage Policy Center, believes LePage and the Legislature will eventually strike a deal that leads to meaningful tax reform.

“It’s a very complicated issue, so however it gets done is going to be talked about and controversial,” Gagnon said.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.