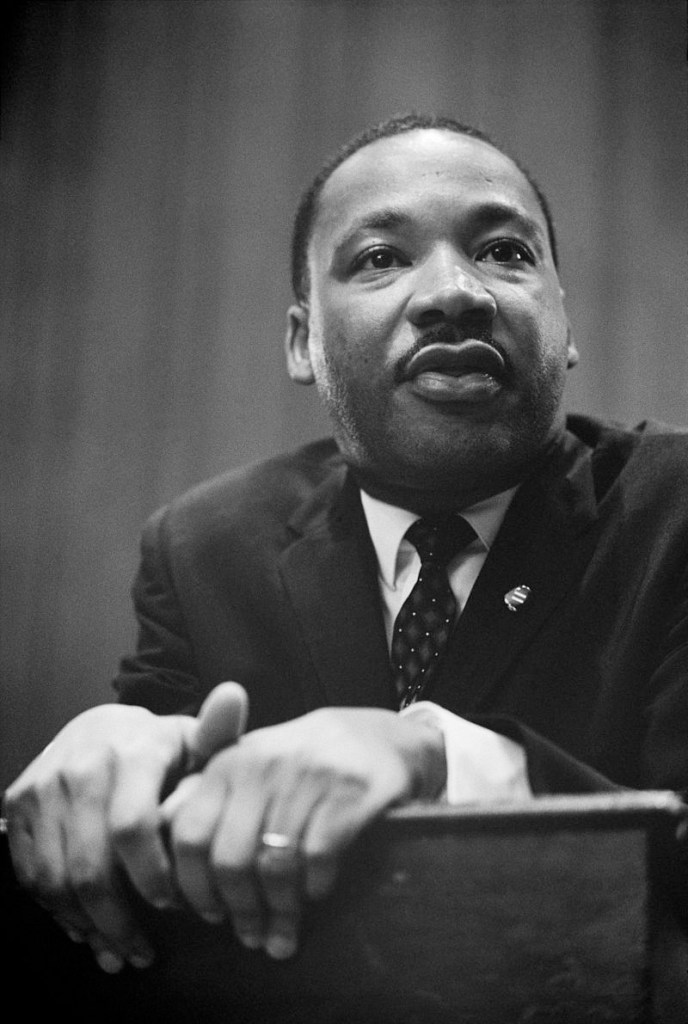

NORTH YARMOUTH — As we celebrate Dr. Martin Luther King’s birthday this week, let us move beyond the tired soundbites repeated each year, and reflect more deeply on the full meaning of his message.

Dr. King believed that a trio of evils – poverty, racism and militarism – existed in a vicious cycle, holding back the true greatness of which America was capable.

He preached that a critical mass of committed citizens could change this, and he put his life on the line in service to these values. He knew that the liberation of African Americans was not separate from that of other groups – Mexican Americans, poor whites, workers and Native Americans.

In his 1964 book, “Why We Can’t Wait,” Dr. King wrote: “Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race. Even before there were large numbers of Negroes on our shore, the scar of racial hatred had already disfigured colonial society.”

Brutal massacres, forced “relocations,” deliberate disease contamination, sterilizations and abortions without consent, the outlawing of religious practices, theft of land and other natural resources, and violation of treaty rights are only part of this legacy. Much of it continues into the present.

As Dr. King said, “Even today we have not permitted ourselves to reject or feel remorse for this shameful episode. Our literature, our films, our drama, our folklore all exalt it. Our children are still taught to respect the violence which reduced a red-skinned people of an earlier culture into a few fragmented groups herded into impoverished reservations.”

Beginning in the 1800s, the U.S. government, along with Christian missionaries, took Indian children from their homes and sent them to boarding schools where they were forbidden to speak their own language, wear their own clothes or practice their religion. Children were often physically, sexually and emotionally abused. Some tried to run away; many died.

Taken from what is now Maine, many Wabanaki children ended up at Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. In the 1900s, Wabanaki children were sent to the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School in Nova Scotia. By the 1950s, the focus shifted from institutions to the homes of white foster parents, where abuse commonly continued. Forcible removals are still happening today.

Many Mainers are not aware of the extent of degradation experienced by the original inhabitants of this land we call home. We may be even less aware of how these histories have affected neighbors and friends who are still living. At this time in our state, however, we have a unique opportunity to learn about and address a portion of these historical wrongs.

The Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission is a five-member panel chosen to investigate what happened to Wabanaki people involved with the child welfare system in Maine. In 2012, Gov. LePage and all five Maine tribal chiefs – Reuben Clayton Cleaves of the Passamaquoddy Tribe at Pleasant Point; Brenda Commander of the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians; Kirk Francis of the Penobscot Nation; Richard Getchell of the Aroostook Band of Micmacs, and Joseph Socobasin of the Passamaquoddy Tribe at Indian Township – signed on to the commission mandate.

The commissioners and supporting staff include both Native Americans and non-Native Americans. Those invited to share their stories include children taken from their homes, child welfare workers employed by the state, parents, foster parents, guardians, judges, police – anyone who has witnessed or been affected by these events.

No judgment or blame is involved in this process. The goal is to find out what happened to people in the child welfare system and to document it. Another goal is to give Wabanaki people a place to share their stories in a safe environment and begin to heal. Many have carried their invisible scars silently for decades. Recommendations will be presented to the state about how to work better with Wabanaki communities.

I became involved in this work because I believe strongly in the power of truth-telling. In my personal life, it has been freeing. On a historical level, I don’t think we can change course or repair injustice without it. As a white woman, I feel a responsibility to help repair the damage done by colonialism, even if most of my ancestors were not here or did not participate in these specific acts.

I am especially impressed with the level of organization, support and thoughtfulness demonstrated by commission workers. A recent “Ally Training” in Portland was informative, lively and free of judgment.

I encourage other Mainers to learn about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and join in its work. Visit www. mainewabanakitrc.org or contact the commission at info@mainewabanakitrc.org or 664-0280 for more information.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.