Claiming self-defense in a murder trial is a far riskier proposition for criminal defendants than many people may think.

Legal experts who spoke this week after 72-year-old Merrill “Mike” Kimball was convicted of murder for fatally shooting an unarmed man during a 2013 confrontation at a North Yarmouth bee farm said it’s hard to predict what details jurors will latch onto or what they’ll reject.

Kimball had been so confident in his self-defense claim for shooting 63-year-old Leon Kelley that he rejected a plea deal to a lesser charge of manslaughter leading up to trial and sought an acquittal before a jury of six men and six women.

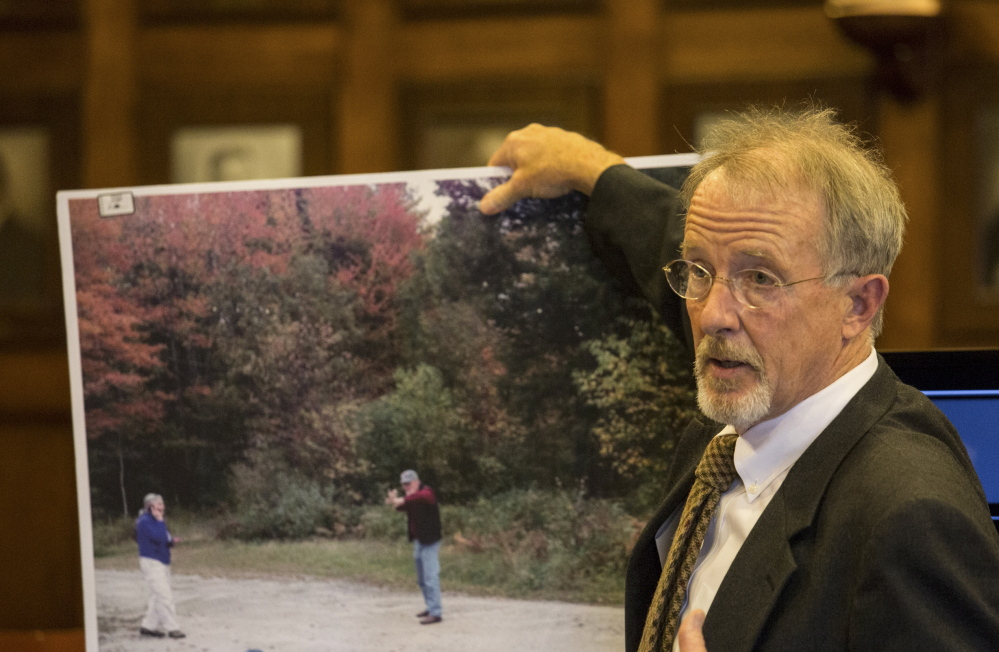

Kimball claimed he shot Kelley, who outweighed him by 115 pounds, after Kelley shoved him backward repeatedly and kept coming at him after he retreated 35 to 40 feet to the edge of a stand of woods.

But the jurors, who have yet to speak publicly about their decision, didn’t buy Kimball’s claim. Rather than walking from the Cumberland County Courthouse as a free man as he hoped, Kimball will now likely spend the rest of his life in prison.

HARD TO SELL

Andrew Branca, a Massachusetts lawyer who wrote the book “The Law of Self-Defense” said that in his experience about 95 percent of all self-defense claims don’t stand up in court.

“These kinds of self-defense cases are really hard to sell to a jury,” Branca said. “You’ve killed someone, and there has to be a damn good reason for that.”

Jim Burke, a professor at the University of Maine School of Law, said he followed the bee farm case because he used to buy bees from the farm’s owner, 95-year-old Stan Brown, and knew Kimball’s wife, who managed the bee farm.

“This jury saw a well-presented case done by competent lawyers, and they came up with a decision. That’s how the system works,” Burke said.

Burke didn’t fault Kimball’s attorney, Daniel Lilley, for taking the case to trial rather than persuading Kimball to take the plea offer.

“You never know – you just plain don’t – so it’s all a matter of calculated risk,” Burke said of jury trials. “It is the client’s decision whether to take a deal or go to trial. And there is only one way to know what the right decision was, and that is to turn down the deal and get the verdict. If you take the deal, you never know if that was the right decision because you never get a verdict.”

THE ISSUE OF RETREAT

The prosecution emphasized several points during Kimball’s trial that may have influenced the jury’s verdict Wednesday after six hours of deliberation.

Kimball came to the bee farm with a concealed .380-caliber Ruger and an extra clip, knowing in advance that there could be trouble because of a rift between his wife, Karen Thurlow-Kimball, and Kelley’s family. Kimball had drunk two rum cocktails before the encounter. And Kimball could have continued retreating, to his left or right on Honeycomb Drive, after backing up the full length of the bee farm sales shop’s driveway with trees behind him, Assistant Attorney General John Alsop said in his closing arguments.

Maine law allows the Judicial Branch to release the names of jurors after a trial on certain occasions when it is “in the interest of justice.” The Portland Press Herald filed a written request Wednesday for the names of the jurors in the Kimball trial, but the court had yet to rule on the request by Friday afternoon.

Portland lawyer J.P. DeGrinnney, who tries cases in the same courthouse but had no involvement in Kimball’s case, said he thinks the issue of retreat was likely central to the jury’s verdict.

“People don’t like gun violence, and if there is any alternative to using gun violence, they expect you to use it,” DeGrinney said.

Unlike many other states, Maine’s self-defense laws require someone who believes he is about to be attacked with enough force to cause serious bodily injury or death to retreat for as long as he safely can before he has the legal authority to defend himself with deadly force.

Maine’s self-defense laws are different for deadly force than they are for non-deadly force. Retreat is not required before using non-deadly force.

“You can pre-emptively punch someone in the face if you think they are going to punch you in the face, but you can’t shoot them,” DeGrinney said. “There is no duty to retreat in the non-deadly force scenario.”

DeGrinney said defending older clients, like Kimball, can be a particular challenge because any prison sentence could mean spending the rest of one’s life in prison.

“Anytime you have a client who is in that age bracket, you really need to go for broke in getting an acquittal,” DeGrinney said. “When you have an older client, they don’t want to do any time. It’s not uncommon for a defense attorney to feel real pressure to try a case to get where their client wants by going to the jury.”

NO SLAM DUNK

Another Portland defense lawyer, Luke Rioux, agreed that self-defense cases can be particularly difficult. He also had no involvement in Kimball’s case.

“Self-defense cases can be tough because, in a way, you concede that your guy committed the act but that he was justified,” Rioux said. “It’s very rarely going to be a slam dunk.”

Rioux said prosecutors can pick apart the justifications, causing the defense to fall apart in the jury’s eyes.

“A lot of people will claim to me that they acted in self-defense, and when you get into the facts of what happened, there is often a fine line in a client’s mind between self-defense and retaliation,” Rioux said. “It’s not a clear path to a win in self-defense.”

Rioux also agreed with DeGrinney that Kimball’s defense would have a stronger argument in a state that does not impose the duty on someone to retreat before using deadly force.

Branca, the author whose book details self-defense laws state-by-state, said only 16 states require someone to exhaust all avenues of retreat before deadly force can be used.

“The duty to retreat is a minority position,” Branca said.

The other 34 states have different variations of the self-defense law commonly known as “stand your ground.” Some of those states, such as Florida, do not require retreat, but allow prosecutors to use that as an argument against a defendant. Other states, such as Texas, prohibit prosecutors from raising failure to retreat against a defendant, Branca said.

“Stand-your-ground states come in several flavors. They are not all the same,” Branca said. “In states where there is a legal duty to retreat, you are required to retreat before you can use deadly force, as long as you can do so in complete safety.”

‘CREDIBILITY IS EVERYTHING’

Branca said the jury in Kimball’s trial may have had other reasons to reject his self-defense claim.

Aside from the issue, every state has the same five basic principles of self-defense. Deadly force can be justified only if the person reasonably believes he is about to face deadly force himself, that the person did not provoke the threat, the need to defend himself is imminent, deadly force is necessary and it can’t be avoided, he said.

“It’s relatively rare to get a legitimate good guy self-defense,” Branca said. “Prosecutors don’t like to bring cases to trial unless they really believe they are going to win. If a self-defense case is robust, it usually doesn’t go to trial.”

Branca said jury trials are further complicated because jurors usually know what happened only from what witnesses say, not from personal observation.

“Credibility is everything,” he said. “The jury was not there. They did not see what happened. They are entirely dependent on the stories being told to them in court.”

Kimball’s sentencing date has not yet been set. He faces a minimum of 25 years in prison and up to life in prison.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.