The NFL’s disciplinary system is so badly broken it may as well not exist. It is grounded in empty posturing. The initial rulings it produces are a weigh station at best, a misuse of power at worst and a waste of time no matter what. By trying to act tough, the league turns scoundrels and cheaters into victims of a Byzantine appeals process that often ends up outside its jurisdiction. It serves no one except lawyers. It makes a mockery of whatever authority the league legitimately has.

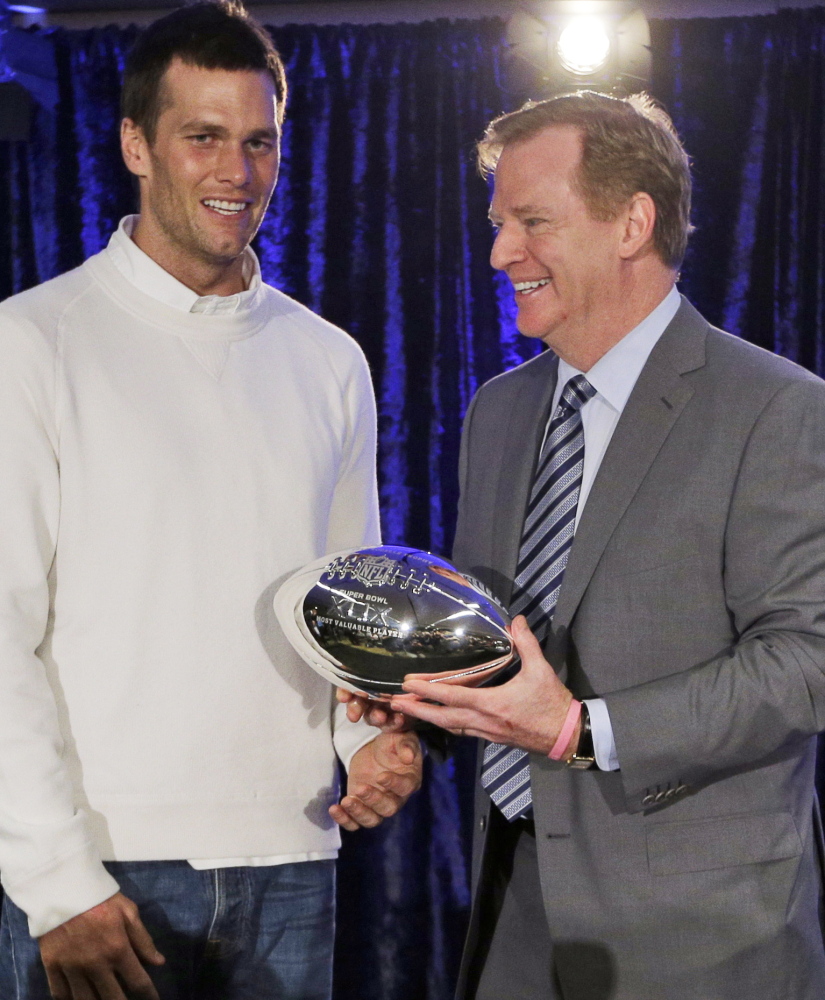

Commissioner Roger Goodell announced Tuesday that – surprise! – he had upheld the league’s four-game suspension of New England Patriots quarterback Tom Brady. And so the Deflategate controversy will plod forward, this time to a federal court, assuming Brady follows up on his plan to sue the league in the event he received any suspension at all. The mess started in January. It’s now mid-July. The NFL has spent millions in legal and investigative fees. Unless dragging one of your most marketable, successful players through the mud counts as progress, nothing has been achieved.

By inserting himself into every phase of the process, Goodell eliminated any outcome that would reflect well on the league. He commissioned the (allegedly independent) investigation. His hand-picked executive vice president, Troy Vincent, issued Brady’s punishment. He heard Brady’s appeal. Each step lacked consistency and dripped with conflict: The Wells Report included questionable science, the punishment was handed down without precedent and the appeal was ruled on by an obviously biased arbiter.

This isn’t about Brady’s innocence or guilt. It is about the creation and application of due process. The stupefying thing about the NFL’s treatment of Brady’s case is it fit into a bewildering pattern. In the past year, judges overturned or reduced NFL-issued suspensions of Ray Rice and Adrian Peterson. Last week, Harold Henderson, an arbiter hand-picked by the league, reduced Greg Hardy’s suspension from 10 games to four.

The perpetrators of reprehensible acts became, in the eyes of judges, the targets of mistreatment. It’s because the NFL continues to issue punishments that make no sense or adhere to no previous standard. They are guessing. The NFL should have been far better equipped to handle Brady’s case. Unlike the three prior cases, it pertained only to the playing field and the rules of the game. Incredibly the league made all the same mistakes, all the same misreads, all the same clumsy wielding of its power.

“This is a league and a commissioner that doesn’t learn from the past, obviously,” said Alan Milstein, a sports litigator who argued against the NFL in running back Maurice Clarett’s fight to declare early for the NFL draft.

“The NFL has got to end the system where it is cop, judge and jury. It’s OK for the commissioner to be the cop. Once he brings charges, or believes that there’s an infraction, then there’s an independent hearing body to decide whether the infraction indeed exists. That’s the problem. And the other problem, the judgments can’t be just thrown against the wall. There’s got to be some reason for them. And there’s got to be some consistency with respect to these infractions.”

What the NFL cannot learn is the limits of its power. Late last decade, after a string of criminal behavior that crescendoed with the preposterous run of arrests by Adam “Pacman” Jones, the NFL and NFL Players Association joined together and shaped the personal conduct policy. But that didn’t change the broad powers the commissioner’s office has held since 1968 under Pete Rozelle. The problem isn’t the policy, it’s the implementation.

“I’ll be the first one to say: It’s a bigger box than I’d like,” said the NFLPA president, Eric Winston, early this summer. “But it’s a box. There are parameters in which he can operate. This was not a problem when Commissioner (Paul) Tagliabue was in office.”

That the NFL has recently seen three of its rulings dismissed or altered shows it cannot stay in that box. The overreach undermines the league’s ability to perform its responsibility.

It’s debatable what lengths the NFL should go to legislate the behavior of players off the field, no matter how reprehensible. (That’s the job of the courts, and now is a good place to point out how shamefully the New Jersey district attorney acted in the Ray Rice case, giving the running back only community service and counseling.)

Perhaps it should have a stake in how players reflect on the league. Perhaps it should allow for other means to regulate the league’s image. There would be natural deterrents for off-field issues – imagine the public pressure on the Ravens if the NFL left it up to the team to decide on Rice’s fate.

The need for the NFL to create and enforce playing rules is absolute. The league office’s primary responsibility is to uphold competitive integrity, which any league is foremost built upon.

Either way, once the NFL decides it wants to mete out punishment for conduct, it must create and adhere to due process. This is where the league under Goodell has failed and failed again.

“The answer to all this is very simple,” Milstein said. “The league and the union should be able to get together and instead of having just the league be the forum for this punishment, it should be a joint enterprise by the union and the league to judge these kinds of infractions. That’s the way to get by it, so it’s not just the league doing the punishing.

“It’s in the union’s interest just as much as it’s in the league’s interest to make sure competition is fair and its players don’t sully the marketability of the NFL.”

The NFL, under Goodell, has refused such cooperation or collaboration. It has viewed players with cold indifference. The first step to fixing the way it disciplines players might be to simply listen to them, to treat them as equal partners in the league’s success rather than just labor.

“The NFL thinks the teams are the league,” Milstein said. “With Maurice Clarett, they believed that no matter how good he was or could have been, they didn’t need him. They were more important than the players. Baseball certainly highlights its people, particularly its young people. Baseball enjoys letting its players be the face of the game. The NFL is not like that. … In the old days you would say it’s IBM, it’s the Soviet Union. It’s this big, nasty, arrogant entity that thinks it’s more important than the players.”

It can think and act that way all it wants, but the NFL has learned its viewpoint does not extend from its offices into the courts. It has led to a wasteful system that damages those in its maw and the league itself. It is a lesson Goodell seems unable or unwilling to absorb. Another debacle, this time with the reigning Super Bowl MVP, gives him another chance to amend a broken system. If he doesn’t care about players, he should at least care about his league’s time and money.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story