Having been born and raised near Bangor, I grew up practically in the shadow of mile-high Mount Katahdin. I first climbed up to Baxter Peak in 1972, when I was 12, and I have stood on that iconic spot seven times. I have hiked the entire Appalachian Trail, and I have climbed nearly all of the 4,000-foot mountains in New England. But Katahdin will always be my special, breathtaking place.

Therefore, recent news stories about how Appalachian Trail thru-hikers could be overusing and abusing Baxter State Park and Mount Katahdin have certainly captured my attention. The issue involving hiker Scott Jurek, in which he celebrated his record-breaking hike with champagne at the summit, has added an air of controversy to the release of the movie “A Walk in the Woods,” which is expected to increase the number of hikers on the trail.

All of Baxter State Park must be treated with loving care and respect, or the wilderness experience that former Maine Gov. Percival Baxter envisioned for all will be lost. This is especially true of the fragile terrain above the tree line on Katahdin. Based on all I have read and seen about the champagne celebration on the mountaintop in July, the park director was probably justified in taking action against the thru-hiker who blatantly broke the rules.

That said, it is patently unfair to paint all thru-hikers with the same brush, and it would be an absolute travesty should Baxter State Park decide that the AT could no longer end on top of Katahdin.

I section-hiked the 2,180-mile Appalachian Trail – between Springer Mountain in Georgia and Katahdin in Maine – from 1990 until 2010. I met many thru-hikers during those 21 years and came to appreciate the efforts of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and the 31 regional clubs that maintain the trail so that thousands of people like me can continue hiking the renowned, 78-year-old footpath.

Certainly the ATC promotes the Appalachian Trail, but the conservancy takes great pains to inform hikers that it is everyone’s responsibility to protect and preserve the trail and the natural environment around it. The ATC constantly preaches the gospel of Leave No Trace – of everybody carrying out everything they bring in. It has been my experience that thru-hikers are the most devoted disciples of Leave No Trace and that they educate less-experienced hikers about ways to minimize their environmental footprints.

While the stories about the dispute between the thru-hiker and Baxter park officials have implied that thru-hikers have an adverse impact on the park, I would argue that the reverse is true. Those who hike to the park affect the environment much less than those who drive to the park, and most thru-hikers are passionate ambassadors of the Leave No Trace guidelines.

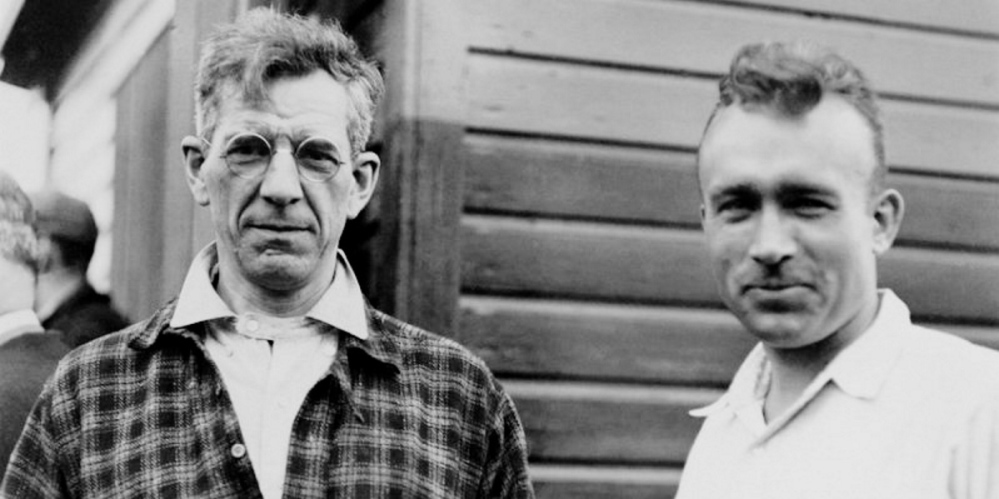

But why should the Appalachian Trail end in the park and on Katahdin at all? Wouldn’t it be better for that environment to simply end the AT someplace else? While I have long been in awe of Baxter’s “forever … wild” vision that has guided the park during its 84 years, I also revere the foresight and dedication of another Maine man, Myron Avery. It was Avery who led the ATC from the 1920s into the early 1950s and who oversaw the completion of the AT from Georgia to Maine. It was Avery who organized many of the trail clubs, including the Maine Appalachian Trail Club, that maintain the trail to this day. It was Avery who first hiked the entire trail – before it was finished. And it was Avery who ensured that the trail’s northern end wasn’t located on top of Mount Washington in New Hampshire, as had originally been envisioned, but was situated on Katahdin more than 300 miles to the north.

While the AT was originally the vision of Benton MacKaye, I believe the trail would have been little more than an obscure line on a map had it not been for Avery’s perseverance. It was through his efforts that people in 14 states along the Atlantic seaboard can now experience wilderness – not just along the trail but in the state and federal parks and forests that the trail connects. And it was because of his example that nearly 19,000 miles have been designated as National Scenic Trails thanks to the 1968 National Trails Act. The Pacific Crest Trail and Continental Divide Trail are among them.

While historic precedence shouldn’t solely determine the location of the AT’s northern terminus, I believe that having the trail end anyplace other than the Katahdin summit would significantly diminish the thru-hiking experience. The vast majority of thru-hikers begin at Springer in the spring. They all know their destination – Katahdin – by the fall. No other place in Maine would afford the same attraction. The satisfaction that an estimated 15,000 hikers have felt while gazing over the wilderness from Baxter Peak, knowing they have just completed the journey of a lifetime, has validated Myron Avery’s vision. Those thru-hikers become environmental advocates who help protect places like Baxter State Park for future generations.

Park officials are right to reinforce the message that everyone must respect Katahdin and the wilderness around it. The ATC and the trail maintenance clubs must continue educating hikers about Leave No Trace and safeguarding that environment. However, it would make no sense to throw out the legacies of two extraordinary individuals because of the actions of a misguided few.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story