BAXTER STATE PARK — Top representatives of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and the National Park Service pledged Friday to work to address concerns about unruly long-distance hikers and overcrowding that have strained relations with Baxter State Park.

Members of Baxter’s governing board, meanwhile, asked to see concrete steps before next spring’s hiking season while stressing that their top priority is protecting the wilderness aspects of a place with “profound significance” to Maine residents.

“I do not want to see this place change. It’s too important to my grandchildren,” said Chandler Woodcock, commissioner of the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife and one of three members of the Baxter State Park Authority. “So as we attempt to work our way through this, I want you to hear one Mainer’s opinion: I’m not real tolerant of people who want to make it something that it isn’t. And I don’t think many people who live in this state are.”

Woodcock’s comments captured the tensions that drew several dozen people – some local, some from hundreds of miles away – to the park’s Kidney Pond Camp on Friday.

HIGH-PROFILE INCIDENT

After simmering for several years, those tensions erupted publicly last July after a high-profile incident atop Mount Katahdin, the northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail.

Ultramarathoner Scott Jurek celebrated his record-setting run of the entire AT – roughly 2,190 miles from Georgia’s Springer Mountain to Maine’s highest peak in just 46 days – by popping a bottle of champagne next to Katahdin’s iconic sign. After pictures of the celebration went viral, park director Jensen Bissell publicly berated the professional athlete for bringing a “corporate event” to a wilderness park and disclosed that Jurek had been issued three citations, including for public consumption of alcohol in the park.

Bissell also used the episode to reiterate Baxter State Park’s concerns about the growing impact that AT “thru-hikers” – the term for those who hike the entire trail – have had on the park. If those concerns were not addressed, Bissell warned, the AT might have to find an alternate northern ending point.

Since then, a task force comprised of Maine and national groups has met or talked monthly to try to address the park’s concerns and avoid a rerouting of the AT out of Baxter because of the misbehavior of a small number of thru-hikers.

Ron Tipton, executive director of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, which oversees the world-renowned trail, acknowledged his organization’s role in the issue and said he was confident that the parties can work together to address the problems.

“We have a challenge,” said Tipton, whose organization is based in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. “The Appalachian Trail is open to the public and in many ways I find it a positive that more people want to hike the trail. But I also must be quick to say that we have to manage, we have to control and in some ways I think we are going to need to restrict that use.”

An estimated 3 million people hike part of the AT each year. While only a small percentage of those people try to hike the entire trail, Baxter officials have been raising concerns for several years that thru-hikers are consuming a disproportionate amount of staff resources.

They say some thru-hikers are flouting restrictions on large groups, celebrate their achievement by drinking alcohol or smoking marijuana atop Katahdin, camp outside of designated areas and try to bring dogs into the park.

‘WE HAVE TO DO MORE’

A record 2,017 long-distance AT hikers entered Baxter last year, up from 970 in 1998, and Tipton said the Appalachian Trail Conservancy expects another record number of thru-hike attempts again this year. Heightening park officials’ concerns, theaters last month began showing a movie adaptation – starring Robert Redford and Nick Nolte – of the best-selling book “A Walk in the Woods” that chronicled author Bill Bryson’s humorous, failed thru-hike of the trail.

“The growth of the AT does not appear to be slowing and may continue for the decades ahead,” Bissell said. “So if we have these issues now, what will they be like in 10 years? How will we deal with the increased growth and perhaps more individuals with behavior that is in conflict with what we consider to be the typical users of the park?”

In response, Tipton said the Conservancy has started a voluntary thru-hiker registration this year and is increasing its outreach to, and education of, hikers about respecting unique rules in parks such as Baxter. The organization is also actively discouraging hikers from starting a Georgia-to-Maine hike in the spring because of the numbers but, instead, is urging people to “flip-flop” their hike by starting in the middle.

“We have to do more and we are doing that now, helping them understand what is to be expected especially in special places like Baxter State Park,” Tipton said. “I think we can change attitudes and change behavior.”

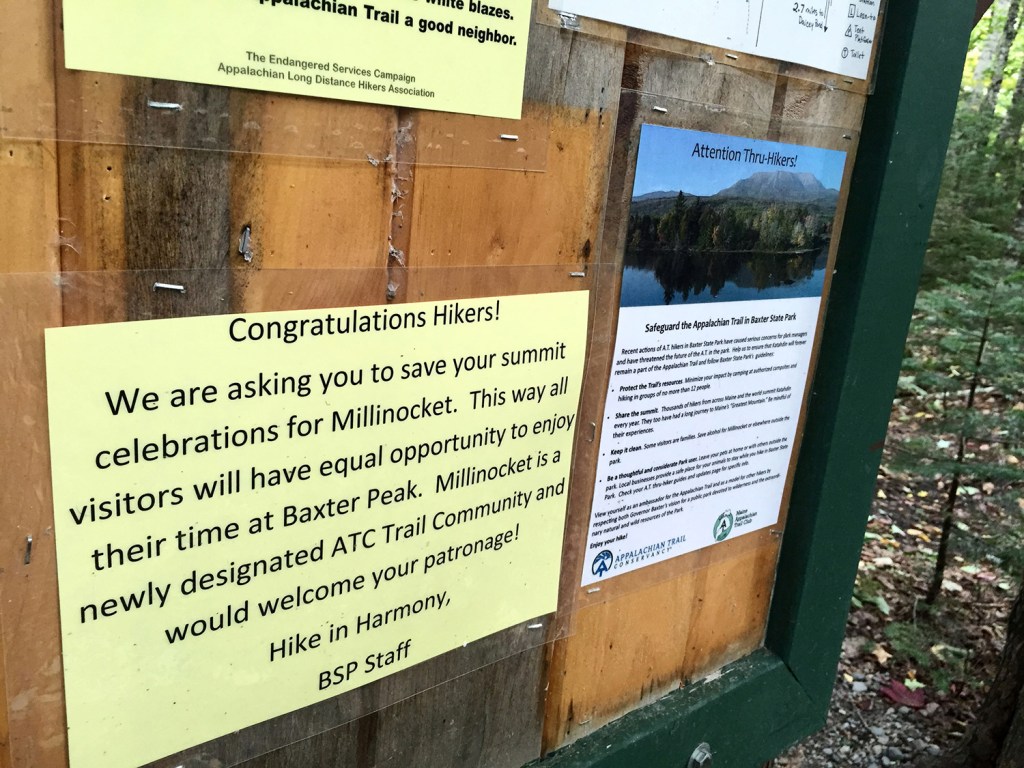

Meanwhile, the Maine Appalachian Trail Club and the Friends of Baxter State Park are stepping up their attempts to educate hikers before they reach Baxter by posting fliers in hiker hostels and shelters as far south as Massachusetts.

“I think the level of public awareness on this is extremely high, probably higher than any other time that I am aware of,” said Aaron Megquier, executive director of the Friends of Baxter State Park. “The level of commitment, spirit of goodwill and interest in resolving that I see from the AT community this is very high. I feel optimistic about the partnership that we have formed.”

Wendy Janssen, superintendent of the National Park Service’s Appalachian National Scenic Trail, said the federal agency is seeing similar challenges along other popular stretches of the AT and at parks across the country. While higher usage is good news, Janssen added, “We don’t want them to love us to death.”

‘CHANNEL GOV. BAXTER’

For the AT, the National Park Service relies on the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and volunteers within 31 trail clubs along the corridor to educate hikers. The park service also recently contracted with a Virginia Tech researcher to study the carrying capacity and challenges facing the trail. That work began in Maine this year because of the concerns raised by Baxter State Park officials, Janssen said.

Another option under serious consideration is a registration or permitting system in Maine – perhaps beginning in Monson, the start of the famed “Hundred Mile Wilderness” – or another system through which hikers would be given a time to summit Katahdin. But such a system would require a coordinating agency, and could be complicated by weather, different hiking speeds and other factors.

Attorney General Janet Mills, a member of the Baxter State Park Authority, stressed several times during Friday’s meeting that the late Gov. Percival Baxter’s intent in creating the park was to preserve a wilderness environment. And it is the park authority’s mission, Mills said, to “channel Gov. Baxter to reflect his sentiments,” as prescribed in the detailed deeds of trust that accompanied the land.

“I don’t think he ever envisioned it becoming a racetrack or the end of a competition, but rather as Commissioner (Woodcock) described, as a place for solace and a place for us to enjoy the wild, and for the wild to remain in its own natural state forever,” Mills said. “I hope you can help us accommodate those desires.”

Baxter State Park’s relationship with the AT – and the question of whether the trail could be moved from Mount Katahdin – has been a hot topic on hiker discussion boards and all along the 2,190-mile trail for months, according to hikers.

David Schreiber, 26, of Nashua, New Hampshire, and Julie Sayles, 20, of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, were enjoying lunch with Sayles’ parents Friday near Abol Bridge before they attempted the final 15 miles of their thru-hikes.

Schreiber, who goes by the trail name “Atlas,” said he first started noticing the posters about Baxter’s unique rules soon after the trail entered Maine a few hundred miles back.

“People are definitely talking about it,” said Schreiber, who said it would be a major disappointment to see the trail moved.

Sayles, who goes by “Little Bear,” said the pair had seen their share of parties and misbehavior along the trail and said it would be a real disappointment if such people ended up ruining the AT for everyone else by breaking Baxter’s rules, prompting the park to move the trail.

“They’re not true thru-hikers, although they are calling themselves thru-hikers,” Sayles said. “Not that I would even if I could, but I’m too tired to be messing around up there.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story