WATERVILLE — Charles Terry grew up on Pleasant Street in the 1930s, a seemingly normal boy until he nearly drowned in Messalonskee Lake at age 4.

Afterward, his parents noticed a change in his personality. He had been found floating face-down in the water, unconscious. He was revived and survived, but his parents wondered whether that near-drowning contributed to his psychological problems later in life.

Terry was convicted of strangling a 62-year-old woman on May 30, 1963, in a New York City hotel. He beat her about the face, strangled her with her scarf, sexually assaulted her with a liquor bottle and left her naked and bludgeoned on the bed, according to police.

Zenovia Clegg was a cancer victim who wore scarves to cover surgical scars on her neck, and Terry reportedly killed her after she made fun of his inability to perform sexually.

Afterward, New York City police Detective Thomas J. Cavanagh Jr. led a team of detectives in pursuing Terry, whom they found on June 6, 1963, at a Greenwich Village bar.

He was arrested and, under interrogation by Cavanagh, confessed to the killing, describing in graphic detail how he did it. He was sentenced to death in the electric chair.

But Terry, who had previous convictions for assault and rape and was described as an intelligent psychopath with deviations in social and sexual conduct, was not put to death. A judge commuted his sentence and ordered that he spend his life in prison.

Cavanagh, on whom the 1970s television series “Kojak” was based, was certain Terry had committed more murders – strangulation murders. In fact, he believed Terry was responsible for some of the murders attributed to the Boston Strangler, Albert DeSalvo, particularly those of women who were ages 55 to 75.

Now a documentary crew, which spent time in Waterville last week, is looking for leads in the Terry case and to explore the possibility that Terry might have committed some murders attributed to the Boston Strangler.

A SON’S MISSION

Cavanagh died in 1996 and did not get a chance to prove that Terry was involved in other murders.

His son, Brian T. Cavanagh, assistant state attorney in charge of the homicide trial unit in the Florida state attorney’s office, Seventeenth Judicial Circuit, is continuing in his father’s footsteps. Like his father, he is convinced Terry killed several other women whose murders matched the Clegg murder profile – including those of the Boston Strangler in 1962 and 1963.

“I owe it to my father,” Brian Cavanagh said in Waterville last week. “He was passionate, too, and I’ve done nothing but prosecute homicides since 1988 myself. I’ve been a prosecutor 37 years.”

Portland Helmich, left, producer for Northern Light Productions, and Brian Cavanagh, an assistant state attorney from Florida, speak about their investigation and documentary on Charles Terry.

Cavanagh was visiting the city – 35 years after Terry died – with a producer and crew from Northern Light Productions of Boston, which is working on a podcast about Terry for the television channel Investigation Discovery. The podcast is for Discovery’s website, and the crew hopes to create a series of 12 20-minute podcasts about Terry, which they expect to air sometime next year. The effort grew out of a Northern Light documentary film project, “Confessions of the Boston Strangler,” which aired Dec. 31.

Portland Helmich, who is producing and narrating the podcast, said the crew was in Waterville to follow up on leads in the Terry case. They were looking for Terry’s relatives or anyone who might have known him or has knowledge of his family. She asked that those with information email her at phelmich@nlprod.com.

Terry was a suspect in the May 26, 1951, strangulation death of Shirley Coolen, 24, whose body was found in a flower garden in Brunswick with a scarf tied around her neck. Terry was not charged in that case.

He also was a suspect in the killing on June 3, 1958, of Patricia Wing, 29, of Oakland. Wing died after a man with whom she was having an affair reportedly picked her up in his car and they parked in a remote wooded area in Fairfield. Her lover, Everett Savage Jr., a business executive from Augusta, was charged with the murder but was convicted only of assault and served time in prison for it.

The researchers wonder if Terry could have murdered Coolen and Wing.

From June 1962 to January 1964, 11 women were raped and murdered in Boston, crimes attributed to the Boston Strangler. Albert DeSalvo confessed to the killings and was sentenced to life in prison in 1967, though many believed – and still believe – they were actually the work of someone else or multiple men. Although DeSalvo confessed to the stranglings, he was not charged with them. Instead, he was convicted of rape and robbery and died in prison.

In 2013, DNA evidence linked DeSalvo to the final Boston Strangler murder victim, Mary Sullivan, who was killed in January 1964.

The documentary will explore whether Terry could have strangled some of the women DeSalvo allegedly killed.

THE MAINE INVESTIGATION

The Northern Light Productions crew and Cavanagh spent three days in Maine last week.

They visited Coolen’s Brunswick murder site, seeking to talk with her relatives and friends. They also were in Augusta, where they spoke with Savage’s granddaughter, Erin Howes, as well as Savage’s son, Brett, and Brett’s wife, Debbie.

“They had always thought it was bizarre that Everett Savage was charged with anything, because he was really a gentle man,” Helmich said.

On Tuesday, the crew interviewed author Barbara Walsh of Winthrop, who, in 1993, as a reporter for the Sun Sentinel in Florida, wrote a story about Tom Cavanagh’s investigation of the Boston Strangler case and the Charles Terry connection.

On Tuesday, Helmich and her crew – Taylor Dueweke, Kate Tibbetts and Sharon Mashihi – interviewed Walsh at the Waterville Public Library. Cavanagh, who had introduced Walsh to his father many years ago, before she wrote her 1993 story, was seeing Walsh for the first time in several years. In addition to interviewing Thomas Cavanagh, Walsh had reported on many of the homicide cases Brian Cavanagh covered in Florida.

“She had the knack for wheedling stories out of me,” he recalled. “She was a dedicated reporter. I always respected her journalistic efforts.”

The crew also visited the VFW hall on Water Street in Waterville to try to make connections with anyone who knew Terry.

Helmich referred often to Maine author Emeric Spooner’s book, “The Boston Strangler From Maine,” which also probes Terry’s possible connections to the Maine murders. It’s dedicated to Thomas Cavanagh.

Few people in Waterville seem to remember Charles Terry. Historian Willard Arnold, however, told the Morning Sentinel last week that Arnold’s maternal grandfather was George Fred Terry II, who owned Kennebec Canoe Co.

George Fred Terry’s brother was Frank Terry, Charles Terry’s father. Frank Terry worked at Kennebec Canoe, which was in the building at the corner of Ticonic and Chaplin streets.

Arnold, 88, said Thursday that he was not sure if he ever met Charles Terry, who he said was persona non grata in the family.

WATERVILLE CONNECTION

Terry was born on May 26, 1930, and grew up at 95 Pleasant St. The house, which is no longer there, was on the block that now houses Kennebec Savings Bank. The Terry house was on the third lot from the intersection of North and Pleasant streets, across Pleasant from where a Mobil On The Run store and gas station are now.

Terry’s family owned a store selling hand-braided rugs, which was in the back of the house. His mother was Oakland native Susie Pelkie Terry. Charles Terry’s older sister, Frances, married Louis Beers and had six children. They lived at 95A Pleasant St.

Terry entered North Grammar School in 1935, then was enrolled in Brookside Elementary and later returned to North Grammar before the family moved to Winslow on Dec. 19, 1941.

In Winslow, he attended grammar school and enrolled in Winslow High School, but quit in the 10th grade, when he was 17, according to research by the research crew.

“Kids described him as a loner, a misfit, angry, didn’t fit in,” Helmich said.

Terry, 6-foot-5 and slim, enlisted in the Marines and served from 1947 to 1949. He received a dishonorable discharge after he was arrested and convicted of stealing an automobile while absent without leave.

While he was raised in a stable environment and had a congenial relationship with his parents, a New York City police report says, the Terrys surmised that his near-drowning at age 4 may have contributed to his maladjustment later in life.

“School records reveal grades ranging from ‘C’ to ‘D’ and he was characterized as a braggart and show-off who failed to get along well with his teachers,” says the report, dated June 20, 1963.

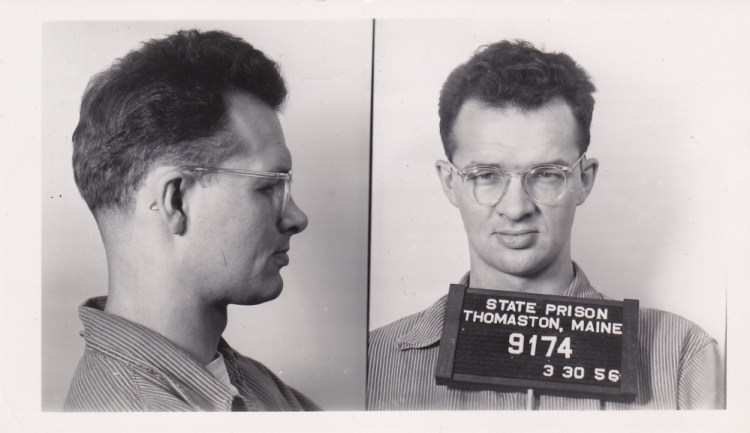

Terry was convicted of raping a woman in 1951 in Kennebec County and was sentenced to eight years in the Maine State Prison. While in prison, he was unpopular with inmates and was charged with destroying state property, drawing obscene pictures and causing disturbances.

He was discharged from custody in 1958, but in 1959, he was sent to prison again for assault and battery on a woman. He fractured her jaw in two places and cut her scalp, according to police records.

In prison, he underwent a psychological examination and was diagnosed with sexual deviation, or sexual sadism.

He married Theresa Lessard LaRochelle, a North Vassalboro native, on Nov. 1, 1958. She previously had been married to Albert LaRochelle, whom she divorced in 1958. She had two children, Deborah, born April 30, 1948, and David, born Nov. 8, 1955, by the time she married Terry.

Charles Terry lived with her until 1959, when he was charged with assault and arrested.

She divorced him in 1961 while he was in the Maine State Prison, but after he was released, he became involved with her again and she gave birth to a son, Mark Shawn LaRochelle, on July 26, 1962. She said Terry was the father, although he disputed that claim.

Terry later lived in New Orleans, New York, Waterville and Boston. He had various jobs over several years as a truck driver, painter and laborer, but couldn’t keep them.

He worked for a short time in June 1962 at the former Crescent Hotel on Main Street in Waterville, but he was fired because he would not take orders, according to the New York police report.

He also was employed by the Wyandotte Worsted Co. in Waterville in 1962, but was fired when his criminal record was discovered.

“He has on at least three occasions in his native Maine undergone examination of his mental condition and has been diagnostically considered an intelligent psychopath (sociopath) with attendant deviations in social and sexual conduct,” the New York police report says.

“In summary, the defendant is an individual with a history of abnormal behavior who has repeatedly engaged in serious aggressive acts and since advent to this city has been leading an essentially unstable, indolent, hedonistic existence devoid of any contact with his more stable family members.”

On April 15, 1981, Terry, who had lung cancer, died after suffering a pulmonary embolism at Attica Correctional Facility in New York. He was 50.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.