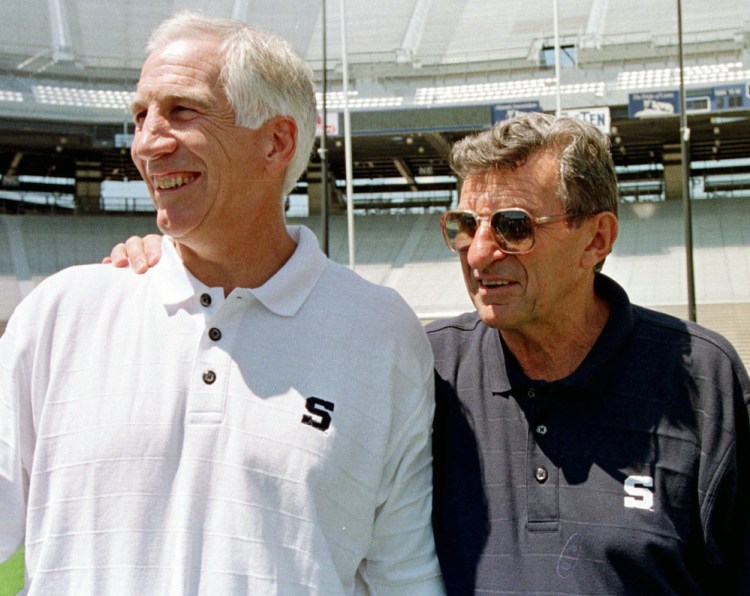

When the Jerry Sandusky child rape scandal was first exposed, it seemed wise to resist the idea that the place had something to do with it. It seemed important to ask whether what happened at Penn State could have happened anywhere, to anyone, given that child predators are so adept at winning trust.

But now it seems that maybe the place was important, because some people up there in that spooky little town still don’t get it. They still think Joe Paterno is the real victim, and the real perpetrator is not Sandusky but the messengers who report his crimes.

You want to know how a serial predator can rape boys in the school showers for 40 years without being caught? It helps when campus leaders habitually deny, duck, parse and distract, because they are so determined to look away from the crime and to protect their bubble of self-regard. Penn State’s president, Eric Barron, is just the latest blame-shifter with a blind spot, one who lacks basic command of vocabulary along with a sense of outrage. Evidence that school officials, including Paterno, may have been more culpable in the Sandusky scandal than previously thought is “incredulous,” Barron pronounced in a statement. Furthermore he is appalled at the “rumor, innuendo and rush to judgment.”

But Barron conveniently diverts attention from a salient fact: indications that Paterno and others may have known more than they admitted comes not from “rumor and innuendo,” but from a judge’s ruling against the school for “enabling” Sandusky. That ruling deserves close examination.

Penn State has sued its insurer over who should pay $92.8 million in settlements to 32 of Sandusky’s child rape victims. One issue is whether Penn State had “notice” that there might be a liability problem and notified its insurer in a timely manner.

A partial summary judgment decision came down from Judge Gary Glazer late last week, and it is simply devastating to the school, both financially and morally.

Most interesting about Glazer’s written decision is the first sentence, which should strike dread in the hearts of Penn State’s trustees. “This case arises out of a series of heinous crimes perpetrated against a multitude of children over a 40-year period.”

Forty years. The reason Glazer chose that broad window is because he led off his entire ruling with an allegation that in 1976 a child told Paterno directly that he was sexually attacked by Sandusky.

Glazer also cited other previously unheard allegations that Penn State coaches knew of molestations by Sandusky and failed to act in 1987 and 1988. Also, he points out, “These events are described in a number of the victims’ depositions.”

It should be noted that an insurance case is not governed by the higher standard of criminal proof but by the rules of civil court. The school issued the following statement: “We note the court’s opinion states the alleged incidents are based upon the deposition testimony of persons who claim to have been victims of Jerry Sandusky. We note these are allegations and not established fact. The university has no records from the time to help evaluate the claims. More importantly, Coach Paterno is not here to defend himself.”

Wick Sollers, the Paterno family lawyer, issued a statement that read in part: “An allegation now about an alleged event 40 years ago, as represented by a single line in a court document regarding an insurance issue, with no corroborating evidence, does not change the facts. Joe Paterno did not, at any time, cover up conduct by Jerry Sandusky.”

Still, Glazer would not have included, much less led with, the 1976 allegation about Paterno lightly or without cause, given the late coach’s stature and fierce public fight over his legacy. We can’t know what’s in the sworn depositions because they are sealed. What we do know is Glazer read them and found reason to cite them.

“As a factual finding, it is carefully stated and, by definition, has an adequate basis to suggest a linkage to Mr. Paterno back in 1976 in order to have appeared in this judicial opinion,” said Thomas Kline, a victim’s lawyer.

Glazer cited school president Graham Spanier and vice president Gary Schultz for apparently choosing “to sweep the problem under the rug.” And he even suggested that Penn State’s failure to report to its insurer that it had a sexual predator on staff – if proven at trial – could constitute “intentional omission of a material fact” and render its policy void.

That’s the context in which Barron issued his highly disingenuous statement May 8. Presumably to placate the vocal and powerful minority of Penn State alumni who continue to bronze Paterno, and perhaps to distract from the import of Glazer’s ruling, Barron launched an attack against “unsubstantiated” news reports.

Those include one by CNN alleging that in 1971 a 15-year-old boy was raped by Sandusky and reported the attack to Paterno and another Penn State official. A day after that report aired, Penn State acknowledged it had paid a settlement to a victim who alleged he was raped by Sandusky in 1971.

Barron is exactly right that no one should rush to judgment based on “incomplete, sensationalized media accounts.” Certainly not.

You should make a slow walk to judgment based on documentary evidence, sworn statements and judges’ rulings.

You’re also perfectly free to make what you will of the fact Penn State reached settlements with 32 victims spanning fully four decades while apparently rejecting some claims.

A settlement is not an admission of guilt. A settlement can be read in various ways. It might represent recognition of a responsibility to a victim or simply represent reluctance to engage in a long, expensive defense. It might be cheaper to pay to make it go away.

But one victim lawyer, Marci Hamilton, believes Penn State is simply unwilling to go through aggressive discovery. Given Glazer’s ruling on notice, “I now look at their quick settlements as evidence that they believed they could keep a lid on the worst of their knowledge,” Hamilton said via email.

Kline said his experience with Penn State was the school didn’t settle cases without carefully assessing them for substance, precisely because it must answer to its insurer if it hopes for help paying.

Kline represented Victim No.5, who alleged he was sexually assaulted by Sandusky in 2001 five months after the infamous day when assistant coach Mike McQueary told Paterno he saw Sandusky assaulting a boy in the locker room.

“I’ve been intimately involved in the litigation process, and there are multiple tiers and levels of process involved in evaluating these claims,” Kline says.

“I can tell you the claims were paid after rigorous vetting and substantiation of a claim.”

Glazer’s ruling becomes particularly interesting on this subject of the sheer multitude of injuries.

“Continuous or repeated exposure to harmful conditions,” he wrote, “is most often considered in the context of environmental contamination.”

This is why Barron’s dodging, blame-shifting statement is so offensive. It suggests that something toxic is still hanging about in the air.

It smacks of the same old persistent pattern of denial by Penn State officials, a deep and still unsolved institutional problem, the instinct to seek cover rather than full acknowledgment.

“It is extraordinarily disappointing that the president of the university would blame the messenger and not the enabler,” Kline said.

Maybe there was, and is, something wrong with the place.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.