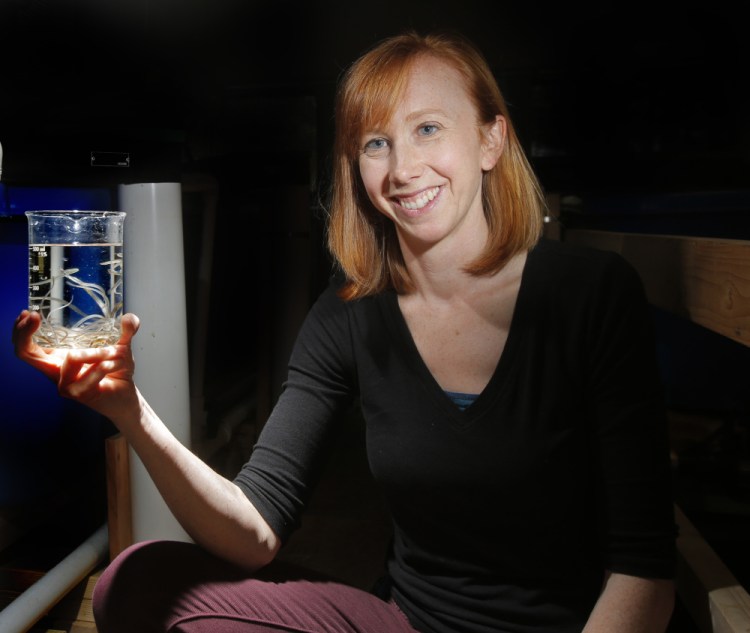

SOUTH BRISTOL — “They are like little torpedoes,” Sara Rademaker says, looking down at a tank full of year-old eels in a feeding frenzy.

Her tone is fond, almost as if the eels wiggling in and out of a submerged laundry basket were a basket of lively kittens, but this is all business. Rademaker is doing what no one has tried to do in Maine before – grow out elvers to eels for the commercial food market.

Rademaker is a young woman, but has 12 years of farming and aquaculture experience. A graduate of Auburn University in Alabama, she’s worked with subsistence farmers in Uganda as part of a U.S. AID project and farmed tilapia in Ghana. She’s taught middle school students how to farm tilapia and lettuces.

Three years ago she began studying European and Asian systems for growing elvers into eels in contained areas, asking herself the question, why not here in Maine, the biggest source of American baby glass eels in the country?

Although she’s just starting her third year developing her eel aquaculture system, she’s gearing up to bring her first eels to market this summer, with plans to tap into the local sushi market to begin with.

“She’s already so far ahead of anyone else in the state,” says Dana Morse, a UMaine Cooperative Extension associate professor and researcher based at the Darling Marine Center. “It’s impressive.”

Earlier this month Rademaker bought 4 pounds of elvers. The price was $1,500 a pound, which sounds like a lot, but down from a high of about $2,200, it was something of a deal. Her dealer didn’t blink at the tall redhead buying fish that would normally be bound for Asia; she knows what Rademaker is doing. Namely trying to get Maine a bigger bang for its buck, eel wise.

It’s not rocket science that caused Rademaker to start working with eels; she was casting around for a new aquaculture project and she saw an opportunity, both for Maine and herself, with eels.

Maine is lucky enough to have an active elver fishery (in the United States only South Carolina does as well, and that is much smaller, with more limited licenses) and plenty of creeks and streams in which to catch the baby American eels (Anguilla rostrata) on their way from their birthplace in the Sargasso Sea to inland rivers and lakes. There many of the species grow to adulthood before repeating the journey in reverse.

Although they arrive in droves, intrepidly making their way on an astonishingly long commute to what will be their adult habitat, American eels were deemed “depleted” by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s technical committee in 2012. They also are listed as endangered in Ontario and the Maritime provinces.

Eels like this one, grown from elver size by Sara Rademaker, have already been used in sushi by chef Matt Howe at Sushi Maine in South Portland. He says he’ll take more when they’re ready.

Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

Worldwide, other species of eels haven’t fared well, either; Europe shut down exports of its baby eels due to dwindling numbers. In Asia, where eel is a much more important part of the cuisine than it is in the States, their native eel, the Anguilla japonica, has declined radically.

Hence the interest in Maine elvers, which are flown to Asia, where dealers sell them to fish farms in multiple countries, including China and Korea. A single elver – remember, they’re tiny, almost weightless – is sold for about $1. In those farms, they grow rapidly in size, thanks to a richer diet than they’d find in the wild, and even more so in value. When harvested at about a year old, they’re worth between $8 and $12 a pound.

While Mainers harvested eel in the 20th century, both as a food source for ethnic markets and as bait, the flavor of the wild eel is not appropriate for say, the sushi market, where its flavors are considered too muddy and wouldn’t command that kind of price. There’s also the question of long-term food safety, because of toxins wild eels might have acquired in their decade or so in lakes, streams and such.

That potential for toxicity is one of the reasons most of the eel you see on menus at sushi restaurants is not wild-caught American eel. The eel you eat when dining out was most likely grown in ponds and processed in Asia. (It could even have been caught in Maine originally, meaning that eel did a vast circuit around the world).

Maine elvers are typically flown to Asia, where dealers sell them to fish farms in multiple countries. When harvested at about a year old, they’re worth between $8 and $12 a pound.

Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

Maine isn’t the right place to set up the Asian-style fish farms, because it would be cost prohibitive to keep the outdoor ponds warm enough. (As Maine’s resident eel expert, University of Maine marine sciences professor Jim McCleave has explained, the eels wouldn’t die, but they wouldn’t grow to market size fast enough to be financially practical.)

But when Rademaker started getting the itch to set up a commercial project in Maine, she came to elvers from a different angle, using a recirculating aquaculture system that could be all indoors and still raise a commercially viable number of fish. Ultimately, if the approach works – and she says it’s going well so far – this would be a means of keeping the long-term profits of the elver business in the state.

“Eels already have a connection to Maine economically,” Rademaker said. “It doesn’t make sense to ship them over and grow them out there.” That’s why she “dove in.”

Another reason, although there’s a big element of the unknown to it – it could be five years or it could be 10 – is that eventually Japan will master reproduction of eels in captivity and when they do? The market will likely fall out of the Maine elver fishery.

MAINE’S GAIN

Rademaker grew up in Fort Wayne, Indiana, the youngest of three. Her father is a veterinarian, her mother an avid hunter, fly fisherwoman and breeder of bird dogs. One of Rademaker’s brothers is a ranger at Glacier National Park, the other is a veterinarian who has taken over their father’s clinic. It’s an outdoorsy, animal-oriented family.

When Rademaker applied to Auburn University in Alabama, she thought she’d be a veterinarian herself, maybe with some sort of focus on fish. But as she studied, that path seemed too oriented to dealing with fish diseases. “Ultimately I wanted to work with live fish,” she said.

She found her way to Maine via an Internet posting. She was looking for the next thing and wanted to find work that combined aquaculture and teaching. A job came up with a nonprofit that fit that description. She’d never been to Maine and she’d never heard of the Herring Gut Learning Center, an alternative education school in Port Clyde. The instructor job was supposed to last 11 months, but Rademaker arrived in 2009 and stayed three years, helping build the program into what it is.

Eels grown by Sara Rademaker at the University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center in South Bristol.

Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

She’s still involved at Herring Gut; on a recent May day, she volunteered with a class of middle school boys attempting to breed tilapia for the first time and needed help sexing and sorting the fish.

The boys hunched over a fish wrapped in a wet towel. They dropped green dye on its underside, trying to distinguish whether it was male or female. Rademaker confirmed their diagnosis: female. But not bulging, so maybe not ready to spawn. “You’ll have to decide if you’ll put her back,” Rademaker said.

The room was humming with the sound of the recirculating system, tilapia in one room, pipes leading out to a greenhouse filled with pristine lettuces in various stages of growth. This is the system Rademaker constructed for the school.

“The parts were all here,” said Ann Boover, lead teacher at Herring Gut. “She just said, ‘Can I change this around so it will work?’ ”

At the end of the lesson, the boys had successfully herded their breeding team into a separate tank, where four females were being hotly pursued by a male tilapia. Only one fish had been dropped on the floor, briefly.

“That’s another reason to work with tilapia,” Rademaker said, smiling. “They are very tough fish.”

A MATTER OF TASTE

When Rademaker started her first batch of elvers, it was in her basement in Thomaston. She did that with a small Sea Grant ($1,000). Then with a grant from the Maine Technology Institute of about $20,000 she was able to rent space at the Maine Aquaculture Innovation Center at Darling. She’s also had help from UMaine’s Center for Cooperative Aquaculture Research in Franklin.

“Little things like that have been so key to doing this in Maine,” she said.

“Everyone I have encountered in the state has been really supportive of the effort, from DMR (Department of Marine Resources) to the dealers to Darling,” Rademaker added.

At Darling, she’s even found some taste testers for her first full-grown eels. She recently served eel smoked, in cream cheese and on top of a cracker to Mike Horst, who is working on a lobster-related project in his own rented space at Darling.

“It was delicious,” Horst said, his eyes widen for emphasis.

Rademaker said she is not typically a fan of “fishy” fish (“ironically,” she said) but this had a very clean and distinct flavor. “There’s nothing like it, which is great,” Rademaker said. “You can’t replace it with something else the way you can with so many white fish.”

She’s already run it by Matt Howe at Sushi Maine, who made rolls with her homegrown eels and told her he’ll be ready for more as soon as she’s ready, which should be this summer. After that she’ll be reaching out to restaurants, like Miyake, famed for its sushi. There’s also some interest in non-sushi restaurants, including Slipway in Thomaston.

In the meantime, there is another batch of babies to tend to, with late-night feedings and all that those entail. These new eels are fresh from some midcoast streams or inlets, although she’s not sure exactly where. As the business grows, she plans to be more specific.

“I want to be able to say, they are from this or that river,” Rademaker said.

Spoken like someone with the fish farm-to-table instinct.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story