WATERVILLE — Verna Buker says if her daughter had not entered a drug treatment program on Thanksgiving Day with help from Operation HOPE, she would surely have ended up dead.

In fact, she has told her 27-year-old daughter, who has been addicted to opiates for years, that she has bad dreams of seeing her in a coffin with her young son standing by.

“She has lost friends to overdoses,” Buker said Monday. “Her best friend was out of jail only a week and died from an overdose. She just had a friend last week die of an overdose. The epidemic here in the state of Maine is horrific. It’s bad.”

Buker, 47, of Waterville, was willing to tell the story of her daughter, whom we’ll call “Sarah,” because she thinks it is critical for people who are addicted to get into treatment because people are dying from overdoses every day.

Sarah was at her grandmother’s house in Oakland the Sunday before Thanksgiving when her grandmother found a hypodermic needle in a soda bottle and called Buker. Buker went to the house and found Sarah there sleeping, her hands and arms black and blue from using.

Knowing she had overdosed twice before, Buker sat down and calmly told her this was it — that she needed to go into treatment and she had found a program that would help her — Operation HOPE, which stands for Heroin Opiate Prevention Effort, a Waterville police department program that focuses on enforcement, education and treatment, with the primary focus on treatment.

Officers try to place people addicted to drugs, who come to the police department for help, into a residential treatment facility, according to police Chief Joseph Massey.

Modeled after the ANGEL program in Gloucester, Mass., and the Scarborough Police Department’s Operation HOPE, the Waterville program partners with the Police Assisted Addiction Recovery Initiative to help those addicted to opiates get into rehabilitation facilities around the country. Waterville police work with officials from Kennebec Valley Community Action Program, Discovery House of Central Maine, MaineGeneral Medical Center and Healthy Northern Kennebec, Massey said Monday.

Buker said she explained the program to her daughter, saying it was her last hope.

“She started having the attitude, getting all defensive,” Buker recalled. “I maintained calm and said, ‘I’m not going to yell at you. These are the options. You can come with me or you can continue down this path,’ and I told her of the possibility of her dying.”

Sarah relented. An addict since age 13, she knew she would never be able to see her 9-year-old son again if she kept using, according to Buker. She had lost primary custody of him years ago and has not seen him in two years. She also has been jailed many times for drug-related issues and is a felon, according to her mother.

Mother and daughter went to the Waterville Police Department two days before Thanksgiving where an officer explained the process to Sarah and got the ball rolling. By 6:45 a.m. Thanksgiving morning, she was on a plane to Virginia where she was admitted to a treatment program.

Buker has spoken to her on the phone since then. Sarah said she loves it there — that it was nothing like what she had envisioned. Young women who have been in treatment longer than Sarah look after her and are good to her, according to Buker.

“She said, ‘I’m in a nice house; it doesn’t look cold and dreary like a hospital,’” she said. ‘”They all keep an eye on me to make sure I’m doing good.”

Taking that first step of going to the police department was difficult for Sarah, but it was the right choice, her mother said.

“They were very helpful to us. They were calm,” Buker said. “They weren’t pushy. They didn’t get into our personal business. They aim for that one person — the individual who seeks help is what their major concern is. They made us feel very comfortable. If it wasn’t for Operation HOPE and Waterville Police Department, I don’t know where my daughter would be today.”

After years of worry and watching Sarah get sicker, go to jail for as long as six months, become a felon, lose jobs and fall deeper into a black hole, Buker said she now feels an incredible sense of relief because she knows she is safe, at least for the time being. She urges others to take advantage of Operation HOPE.

“I don’t want people to feel like the Waterville police department will look down on them or judge them,” she said. “I want them to know it’s a safe place to go and they’re there to help.

“Don’t be ashamed. Some people are so ashamed to say my son or daughter is a drug addict. I’d be ashamed to keep it a secret and not seek help. If you love your child, you’ve got to push and push. Don’t ever give up.”

LOST CHILDHOOD

Sarah started experimenting with drugs at 13. After she dropped out of high school at 17 and had a baby a year later, her drug addiction got worse, her mother said.

“It started off with Vicodin. Then it was the Percocet. Then heroin,” Buker recalled. “She was always calling me up and saying, Mom, I owe someone some money and if I don’t pay them, they’re going to bash my head in.’

Unbeknownst to Buker, Sarah wanted the money to buy drugs. As her addiction worsened, Buker saw her daughter’s attitude change. She became unhappy and withdrawn and her mother couldn’t do anything right. Sarah accused her of loving her brother more than she loved her, she said.

“It just continually got worse and worse and worse.”

When Sarah was young, she lived with her mother and her stepfather and got everything she ever wanted. Money was not an issue, according to Buker. But it was an abusive situation so they moved out. After that, Sarah had a difficult time adjusting to not having as much, she said. She thinks that’s what triggered the experimentation with drugs.

Later, Sarah bounced from place to place, never having her own apartment.

“She lives with whoever she can hook up with, a friend’s house, my mother’s house. She couldn’t hold down a job. She had prior felonies for drug possession.”

Her friends weren’t really friends at all — they were enablers, her mother said.

Buker researched drug addiction and looked long and hard to find a place for Sarah to get treatment, but it is difficult and most places won’t take someone who has no insurance, she said. Beyond that, many people see an addict as someone who chooses to be addicted, but that is not the case, she said.

“No one chooses to be an addict,” Buker said. “It’s a disease. It’s an illness. A lot of addicts choose to use heroin because of prior medical issues such as depression, anxiety. I know my daughter deals with depression. She was diagnosed years ago with it, so if she could be on something for her depression … but she doesn’t have any insurance. She couldn’t afford insurance. She can’t hold down a job. No one will hire her because of her record.”

SAVING PEOPLE, ONE AT A TIME

Since the Waterville police department started Operation HOPE in January, it has helped 30 people enter treatment, according to Massey. Nine dropped out during the early stages and 21 were placed in treatment. Dozens more, who Massey believes are addicts interested in getting into the program, have called to ask questions about it.

The difficult part, he said, is convincing people to come to the police department to take the first step.

“There’s certainly a need out there, but it’s reaching them and getting them to come in,” he said.

Over the last decade, police have seen opiate addiction reach an epidemic level, he said. It devastates not only the person addicted, but also his or her family, he said.

“I think that the opiate addiction issue right now is probably one of the most pressing social challenges we’re facing,” he said.

Massey, who has responded to calls for death overdoses himself, believes there must be a national strategy and funding to address the problem.

“It’s a real pressing issue for us, and we at this level see people every single day addicted to opiates,” he said.

The medical costs associated with addiction are enormous, and the traumatic effect on families requires more help on the local level, he said. His department is trying to come up with outreach programs to enhance Operation HOPE, but everything costs money and the program survives on donations.

“It takes a lot of department resources — it really does,” he said.

Three police officers must work on a case initially, and then volunteers known as “angels” come in and make calls to treatment facilities around the country that will take the opiate-addicted person.

“It’s very difficult finding a bed for them,” he said. “Many of those facilities won’t take them if they need de-tox.”

In the case of Sarah, the flight was 10 minutes early so she missed it. A police officer had to speak at length to airline officials to convince them it was critical she be placed on another flight and not lose her ticket, Massey said. Toiletries for those addicted to opiates are kept at the police station so they are able to stay there until they are placed in a facility and can get a flight.

The police department solicits donors to provide funds for scholarships and airline tickets. Working with KVCAP, MaineGeneral, Discovery House and Healthy Northern Kennebec has helped with fundraising and finding de-tox centers, but it is an ongoing battle.

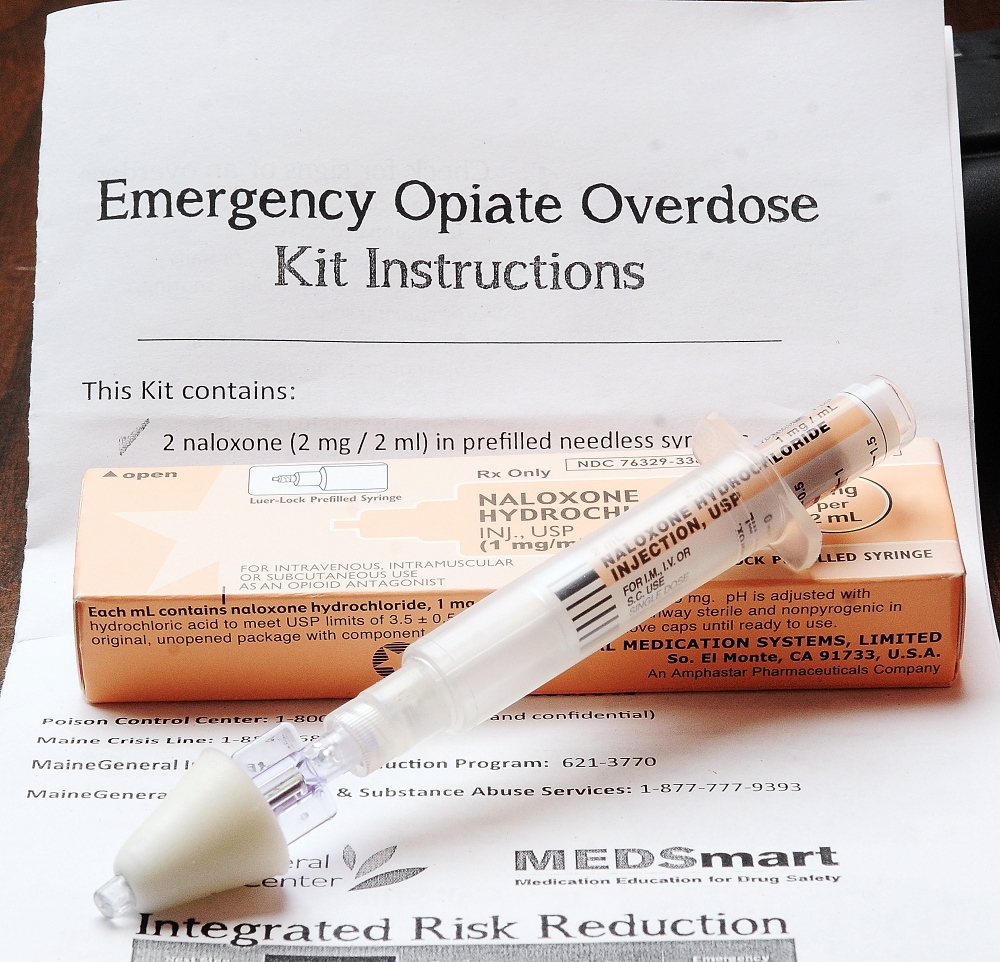

“We lose more than one person a day in Maine,” Massey said. “We have hundreds of overdoses where Narcan is used.”

Sometimes a person who overdoses and is revived overdoses again in the same day, he said.

When Massey’s department started Operation HOPE, it did so with the philosophy that if it could save one person addicted to opiates, it will have been worth it.

“It’s a scourge in our community, and we need to do everything we possibly can to find treatment for those willing to come and access the program,” he said.

Meanwhile, Buker urges people to donate to Operation HOPE, which got Sarah to the first step.

Operation HOPE, which survives on donations, paid for Sarah’s flight to Virginia and 30 days in the treatment facility, but after that, she must get a job and pay $125 a week to stay there, according to her mother.

“I’m very hopeful,” she said. “I have to be positive, just like she is right now. Her sobriety is everything. There’s been numerous time I have cried and cried and cried and got to the point I was so depressed. I lost so much weight over this. My daughter was in the hospital emergency room once and the rescue workers said she died twice on them. She literally died twice and they revived her.”

Amy Calder — 861-9247

Twitter: @AmyCalder17

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.