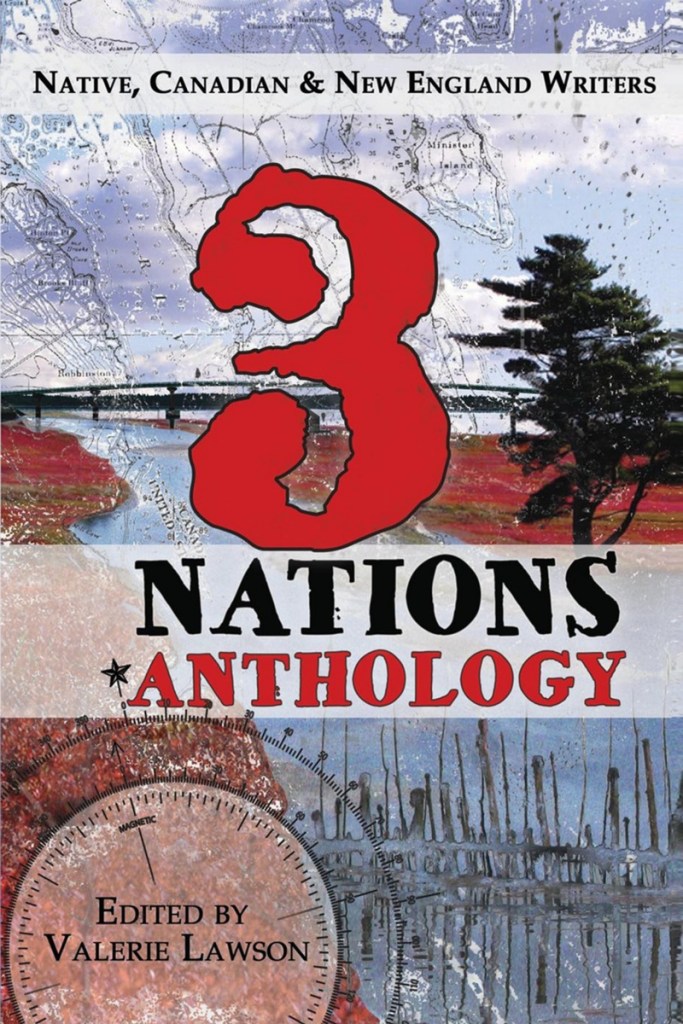

Anthologies are strange beasts, but perhaps that is especially fitting for Valerie Lawson’s project, “3 Nations Anthology: Native, Canadian & New England Writers,” since it is so deeply focused on nature and its sovereignty over itself.

The anthology is exquisitely edited by Lawson, using theme as an invisible connective tissue among the pieces, allowing the various narratives to flow in a sequence. Broadly speaking, the prose and poetry shift focus from the land to trees and logging to rivers to animals and ending again with a deep meditation on the land and its connections with humanity. Missing, unfortunately, is any kind of editorial introduction to the choices made in the work, or information on how the project formed; some of this can be found at the press’s website.

The three nations of the anthology’s title are the United States, Canada and the Native and First Nation people’s lands – like the Penobscot Indian Island Reservation – that are sovereign nations within the borders of other countries and recognized as such. The borders are porous between these nations, especially in terms of culture and love of land, which is shared among the people of all three areas. In “Borderline,” Stephanie S. Gough describes Campobello Island, population around 900, which is Canadian although there is no direct land route to the Canadian mainland. A bridge connects the island in Passamaquoddy Bay to Maine, so that its residents must cross a border checkpoint whenever they go off-island by land. Come summer, Campobello residents can reach the Canadian mainland by ferry, though it requires two different ferries to do so. Gough writes about these crossings, what you can and can’t bring through, and what people hid from customs (alcohol, fruit, layers of new clothing underneath older outfits to avoid exorbitant taxation). “When I want to go to a bar,” she writes, “I cross a border. For many years, I could only buy groceries if I left my country, and still today, I can only gas up that way.”

But the anthology is about far more than borders. It deals intimately with both land and water. In “What It Is For,” Cheryl Savageau describes a conversation she has with a friend as they drive through a forest of short trees, only 4 feet tall. The friend asks Savageau, “But what is it for?”, and Savageau has a hard time answering. “It’s for itself,” Savageau says, and later in the essay she continues, about the friend: “What is it for? The language that inhabits her, that inhibits her, says that these trees, this forest, are objects. What I see as beings, as a nation of trees, she sees as, not exactly non-living, because she would admit that trees are alive, in a limited way, but they have no sovereignty, no personhood.” Savageau, however, sees the trees as independent of humanity, not serving its purposes.

Nature dominates the anthology. In an essay titled “Sweetfern,” writer Barbara Chatterton describes a summer spent picking blueberries on the barrens, a section of land that glaciers scraped through eons ago. “It’s this amazing tradeoff that nature does,” one of the boys she meets that summer tells her, “creating something unusable but at the same time making sure there’s something special that can only work in that spot.” Later in the essay, Chatterton adds that this is true of humans as well: “Nature creates us in such a way that we require contact, even though we are changed by it.”

And humans change nature, too, of course. Poet Carol Hobbs writes of roast moose: “Tastes like bark, like brush, / like that too slim distance / from the hunt.” The writers in this anthology don’t shy away from hunting and fishing, nor from describing the destruction of fisheries and beaver dams. They criticize their governments and praise their elders. Ultimately, the intimacy of these works will sometimes go over the heads of those readers not familiar with the land and ways of life these writers share with it and with each other, but that doesn’t mean we outsiders cannot access the beauty, reverence and rage in the works.

Ilana Masad is a book critic and fiction writer working on her Ph.D. at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, StoryQuarterly, Broadly, the Washington Post, the LA Times and more.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.