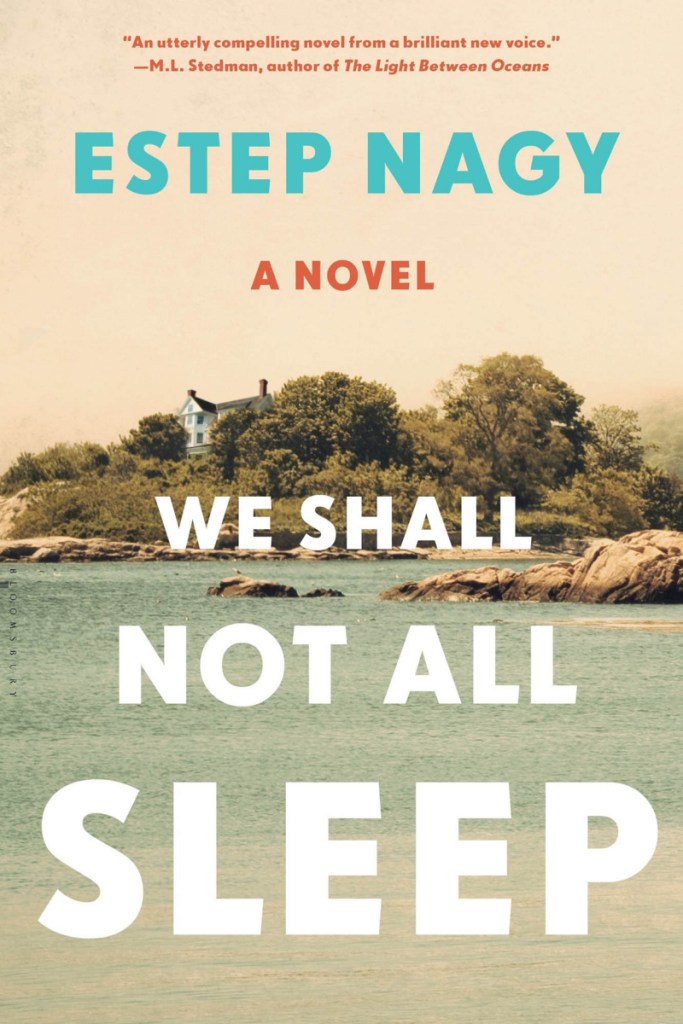

It’s entirely fitting that a novel focusing on secrets should open with a bit of narrative misdirection. Estep Nagy’s “We Shall Not All Sleep” opens in the summer of 1964 with a man named John Wilkie on his way to visit a group of old friends residing on their family’s property on Seven Island in northern Maine.

There’s a sense of shared history here: Jim Hillsinger and Billy Quick married sisters, Lila and Hannah. Hannah has, as of the novel’s opening, recently died under as yet unrevealed circumstances, and a new generation is slowly coming of age.

From this description, one might assume that this is a story of intrigue among the well-to-do, a sort of comedy of manners in which long-festering grudges come out into the open and social mores play a significant role in the narrative permutations. That’s not really what’s happening in Nagy’s novel, however – or, at least, it’s not the only thing.

The novel opens with Wilkie, who has ties to both families but who’s also something of an outsider – and thus, serves as a solid surrogate for the reader as far as enveloping them in this world. “As a rule, the Hillsingers and Quicks each saw themselves as the embodiment of some Seven spirit and the other family as relative barbarians,” one early passage goes, establishing the conflict between the two families.

There are layers of conflict atop that: Early, we learn that John’s friendship with Billy had been irreparably damaged as a result of Hannah’s political beliefs. In the time since then, Lila had connected with John to learn more about her brother-in-law, and John and Jim became friendly.

“We Shall Not All Sleep” opens with John bound for Seven Island for the first time in 15 years, satisfying a long-standing yearning that had persisted ever since his initial visit. Nagy’s writing emphasizes the naturalistic elements of the space, from the sheep that populate the island, to the handful of smaller islands that neighbor Seven Island, to the means by which the tide affects the local geography.

Estep Nagy

A subplot involving Jim and Lila’s son Catta, who’s faced with a test of his character involving spending the night alone on a nearby island, increases the sense of place even more, while also serving to illustrate the extent to which these affluent families are less aware of the working-class goings-on around them.

Nagy’s narrative moves among the characters. Although John Wilkie’s is the first perspective seen, he’s far from the only character that the novel follows. In one chapter, the history of Seven Island and its ownership is revealed: The families to whom it was granted made their initial fortune by hunting British ships in and around the Revolutionary War, which led to their being given this land as a kind of payment. Here, then, the novel enters the realm of official histories and secret histories, and the question of who profits and who is ruined as a result of them. And it’s through this aspect of the book that the relationship between the current generation of the Hillsingers and Quicks – and John Wilkie, for that matter – is further complicated.

That the novel is set in the summer of 1964 is no coincidence. It’s a tumultuous time, and the then-current state of American politics and the looming war in Vietnam (this novel is set shortly before the Gulf of Tonkin incident) are both frequent subjects of discussion on Seven Island. Through a series of flashbacks beginning in 1941, Nagy also fleshes out the novel’s characters, particularly Hannah. It’s a wise narrative decision: Though Hannah’s absence is clearly felt in the present-day scenes, these glimpses into her past allow for her to become a more fleshed-out character, and for her role in this complex familial dynamic, further complicated by Cold War concerns, to be revealed.

Nagy introduces questions of espionage and betrayal gradually into this story of buried secrets, hidden connections and well-off families. And while the novel’s large cast means that some subplots read as more interesting than others, there are also some interesting resonances along the way: watching how multiple generations interpret questions of masculinity in different ways, for instance.

This is a novel in which characters grapple with impossible moral questions, and the repercussions of certain decisions can echo across the years. While the setting of “We Shall Not All Sleep” is idyllic, the human drama at the center of the novel is frequently gripping, making for a memorable fictional study of contrast and conflict.

New York City resident Tobias Carroll is the author of the novel “Reel” and the short story collection “Transitory” and has reviewed books for Bookforum, the Star Tribune and elsewhere.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.