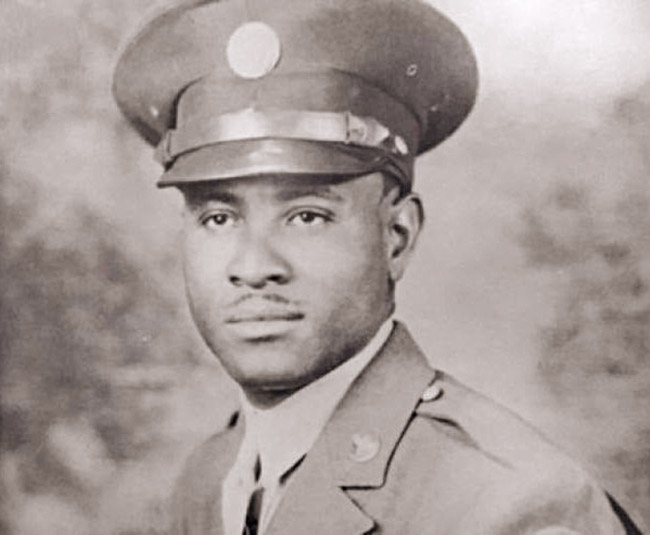

Richard Overton, the grandson of a slave, worked in a furniture store and as a courier for decades until he finally retired when he was 85. That was more than 25 years ago.

Now, Overton – the country’s oldest living World War II veteran – has been enjoying a bit of fame for his longevity, and has a regular stream of visitors to his home in Austin, Texas.

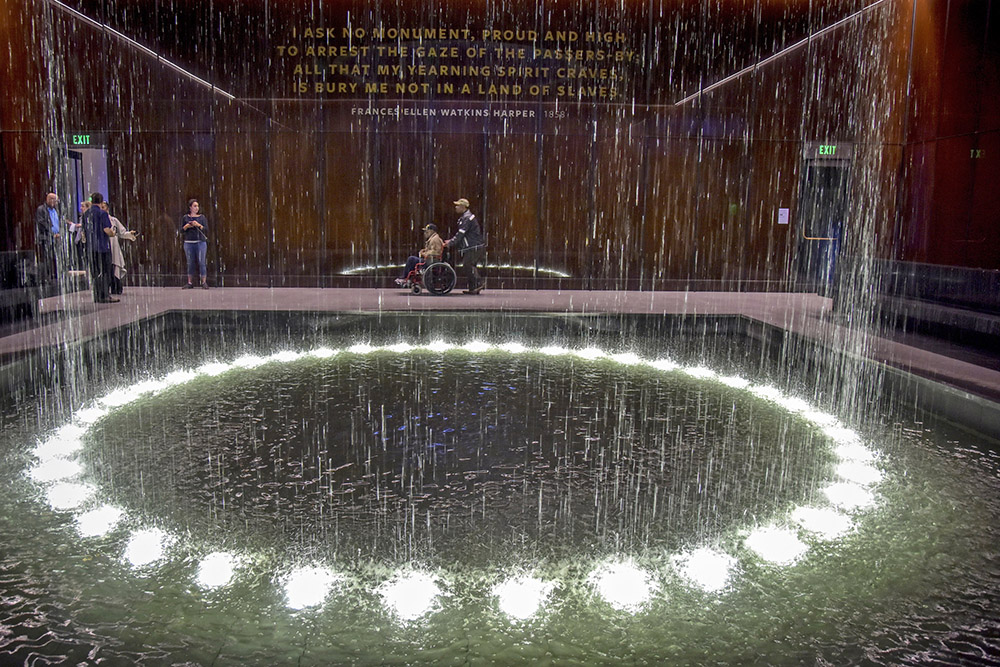

Last week, he mentioned to one of his visitors that he’d like to someday see the National Museum of African American History in Washington, D.C.

The following morning, Overton and a few friends were on a private jet heading toward the nation’s capital. They got a private tour of the museum before it opened to the public Sunday morning.

It was one in a line of stunning and unlikely happenings for Overton, who is believed to be the oldest living American and the third-oldest person in the world. His 112th birthday is next month. His secret to a long life includes cigars, whiskey and speaking his mind.

“I enjoyed every bit of the tour,” Overton said at the museum as he was lunching on soul food.

Then he added, “I didn’t see my name up there,” referring to the World War II exhibit.

His friends chuckled.

“One of these days it will be,” he assured them.

The whirlwind tour was put in motion after one of Overton’s friends, Allen Bergeron, introduced him to billionaire philanthropist Robert Smith, who donated $20 million to the museum. Bergeron knows both men through his work with the Austin Military Veterans Program.

Bergeron said he has been trying to introduce the two men for years; Smith’s father and grandfather served in the military, and Overton served as a sharpshooter in Pearl Harbor and Okinawa.

On Friday, he was finally able to bring Smith to Overton’s house for a visit.

The two men talked for two hours and ate fried catfish. That was when Overton said he’d like to see the museum. Smith replied, “What are you all doing this weekend?” according to Bergeron.

It was settled.

While they were on the tour, retired four-star general and former Secretary of State Colin Powell, who is on the museum board, called Overton to welcome him. The two had never met.

“Everything we do with Mr. Overton turns magical,” Bergeron said, adding that a street in Austin was recently named after Overton.

Overton has been to the White House several times and met President Barack Obama. When he came across the museum exhibit featuring the former president, he sat up a little taller in his wheelchair.

“Yes, sir!” he said. “That’s my friend.”

Asked if he had been nervous to meet Obama, he shook his head.

“He’s a good man,” Overton said. “It was like meeting anybody.”

A few years later, when Overton turned 109, he was still tending his own lawn and driving his own car. He celebrated that birthday with cigars, milkshakes, burgers and a big party.

Although life after 100 has been exciting for Overton, there have also been frustrations, said his cousin Volma Overton, who oversees his care.

“His mind is strong, but his body is frail,” he said.

Volma Overton said he wants to keep Richard Overton in his house where he’s happy and comfortable. People stop by every day to see him, many of them strangers who have read about him in the news, he said.

“His front porch is his everything,” said Volma Overton, 70, who works as a greens keeper on a golf course. “It’s his throne.”

Richard Overton’s veteran’s benefits would pay to move him to an assisted-living facility, but Volma Overton said that would “kill him.”

Volma Overton began round-the-clock care at his cousin’s home a year and a half ago, but at $15,000 a month, he couldn’t afford to maintain it. He started a GoFundMe page, which raised more than $200,000, but that money has been spent on in-home care, leaving the family in debt.

Richard Overton does not have children. He married twice; he and his first wife divorced in the 1920s, and his second wife died in the 1980s.

“He’s outlived almost everybody in his family,” Volma Overton said.

He was born May 11, 1906, in Texas, and served in the Pacific Theater from 1942 to 1945 as part of the all-black 1887th Engineer Aviation Battalion.

He grew up hearing his grandfather’s stories of being a slave in Tennessee. When his grandfather was freed, he moved to Texas, where his family settled.

On Sunday, Richard Overton said it was meaningful for him to see the museum and the African American story through time: from his grandfather’s history as a slave to his own history as an African American fighter in World War II and then the pride of the first African American president.

“All of it is important,” he said. “I’d seen some of it before, but I’ve never seen it all at once.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.