One day in 1951, the painter Grace Hartigan took a gig as a model at the Art Students League in New York. She was serious about her work and already had a solo show under her belt, but she needed the money. Hartigan was naked on a platform, earning 95 cents an hour, when artist-instructor Will Barnet started to expound upon work being done by Willem de Kooning and others in the avant-garde scene.

As author Mary Gabriel recounts in her marvelous book “Ninth Street Women,” Hartigan bristled at Barnet’s assessment. From the platform, she unleashed her opinions about how he was getting it wrong, and then she dressed and left the studio. “It was just too embarrassing to be standing there, nude with an instructor arguing with you about your art,” Hartigan said later.

As art world dramas go, this one barely registers. Abstract expressionism cleared new cultural territory with a lot of Sturm und Drang, and Hartigan herself was no stranger to controversy. She famously relinquished care of her young son so she could live fully as a painter.

Still, her protest from the model’s stand feels emblematic of the paradoxical times. Smart, driven and opinionated, Hartigan and her female peers were respected by their male counterparts, yet also framed by gender. The legendary instructor Hans Hofmann once complimented Lee Krasner’s drawing by telling her it was “so good, you would not know it was done by a woman.”

Modern art was hard for everyone, but it was differently so for the women who lived to make it.

Gabriel, a former journalist, earned acclaim for her 2011 biography of Karl and Jenny Marx, “Love and Capital.” She is a gifted storyteller and a dogged researcher. She puts these gifts to excellent use in this panoramic take on the 20th century’s American art revolution.

Born of the alchemy of young artists and thinkers in the ’40s and ’50s, abstract expressionism was a shock to the system. With its full departure from representationalism, it was received by the masses as an act of hostility, a dangerous expression of Marxism or a prank.

Hartigan, Joan Mitchell and Helen Frankenthaler were beacons of the movement’s second generation. Krasner and Elaine de Kooning were key to the first. Along with Jackson Pollock, Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell and others, they formed a community of visionaries dedicated to the cutting edge.

From childhood, Krasner seemed destined for the artist’s life. As a young student laboring in classical techniques, she felt liberated by European post-impressionists, whose rule-breaking works encouraged her to seek her own artistic voice. During the Depression, she worked in the Works Progress Administration’s mural division, where once she was asked to complete a mural that Willem de Kooning couldn’t finish. “It was a sign of Lee’s standing that she and de Kooning would be considered interchangeable on an important project,” Gabriel writes.

In 1941, Krasner was invited to be part of an exhibition by French and American painters. Pollock was the only American artist she didn’t know. “It irritated her that she had never heard of him, and even more so when she learned he lived around the corner from her on Eighth Street, next to Hofmann’s school,” Gabriel writes.

Krasner would find and fall in love with the action-painting legend. Bewitched as she was by Pollock’s work and by the man, it was Krasner’s fate to suffer his alcoholism and emotional rages, to become his widow and to be defined in relation to him. But as Gabriel shows, Krasner’s work – on canvas and as a touchstone within the community – stood on its own.

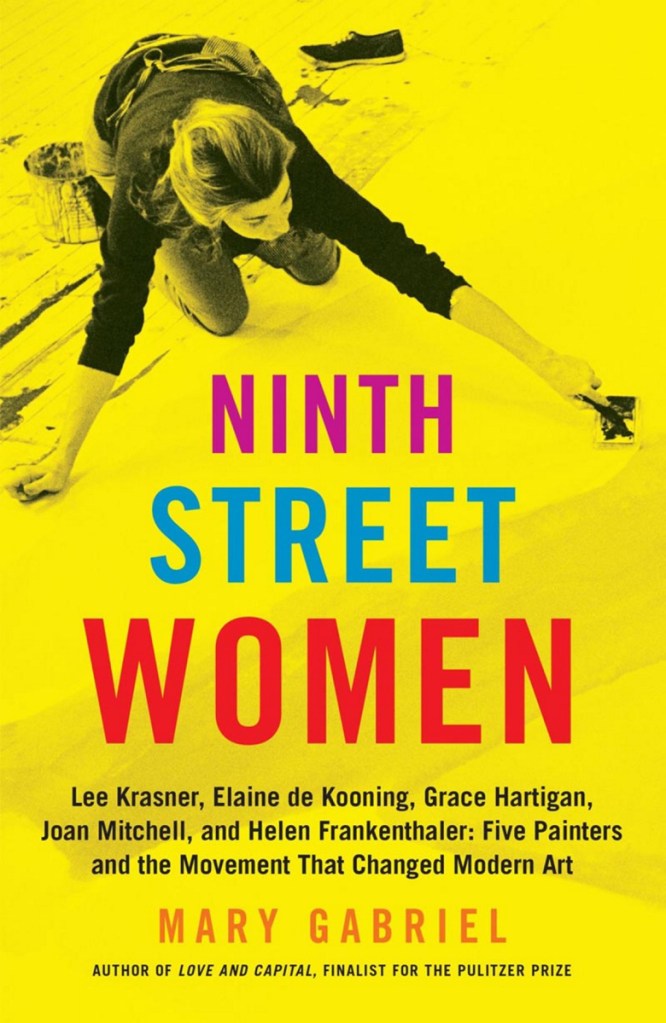

Elaine de Kooning was at times similarly reduced to “wife of” status, although she forged a long career as a painter and a critic for ARTnews magazine. In 1962, she was commissioned to paint President John F. Kennedy. Gabriel writes that de Kooning was expecting to have one last session with him when he was assassinated. She didn’t paint for a year. These stories are brought further to life through 48 pages of evocative images: reproductions of paintings as well as photographs of the artists posing amid canvases, relaxing on the beach, and partying in clubs and at show openings. The visuals support Gabriel’s descriptions of her many characters and help the reader better understand each artist’s contributions to the scene.

“Ninth Street Women” masterfully unspools the biographies of its central cast and scores of supporting players, including the critic and starmaker Clement Greenberg, patron Peggy Guggenheim and writer Frank O’Hara. It takes us into their Greenwich Village haunts and hangouts, and it rummages through their relationships, too often fueled by alcohol and dizzying infidelities.

These artists’ lives, of course, cannot be separated from their times. They survived the Depression, World War II, McCarthyism and a mass culture of conformity. And oh, the poverty. Even star couples like Pollock and Krasner and the de Koonings struggled to make rent well after they’d begun to earn critical acclaim. Yet a traditional existence would have been unthinkable to any of them.

More than a compilation of biographical tales, Gabriel’s book is a reminder of the importance of women to an artistic genre long associated with masculinity. But it is also is a vivid portrait of the very nature of the artist. The stars of the era suffered and sinned as mortals, but their works – and their creative appetites – were otherworldly. “Ninth Street Women” gets us a just a little bit closer to their galaxy.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.