A few seasons after Jackie Robinson retired, Frank Robinson did something Jackie only dreamed of, something he swore never to do, something that ate at him for as long as he was on the diamond.

Frank Robinson fought back. Against a white player. A star white player, too, Eddie Mathews of the Braves.

Robinson lost the fight but won the war.

“I had a homer and a double, drove in one run, scored another and made a catch that robbed Mathews of an extra-base hit,” Robinson said after his eye was blackened. “We won the second game, 4-0.”

Jackie Robinson was revered for the abuse he took. Frank Robinson, if you read the memories that poured out Thursday on the news of his death at 83, was respected for what he didn’t take.

The Mathews incident reverberated not unlike when Larry Doby became the first black player to retaliate against a white player by punching out Yankees pitcher Art Ditmar in 1957. William Jackson in the black-owned Cleveland Call and Post wrote: “They say that Abe Lincoln freed the slaves about 93 years ago and delivered the Emancipation Proclamation. But it wasn’t until Doby threw that left hook to the chin of Ditmar that the Negro baseball player was completely emancipated.”

Frank Robinson was an emancipated black athlete. He played not just fiercely, as was recounted, but most importantly, fearlessly. It was so evident to those who played with and against him that they dreaded him.

In Jackie Robinson’s rookie season, 1947, he was spiked purposely by Enos Slaughter, the southerner who rumor held considered striking that year rather than play against the majors’ first black player since the 1880s.

Ten years later, in his second season, Frank Robinson did the spiking. He sidelined Milwaukee shortstop Johnny Logan, a white player, for six weeks.

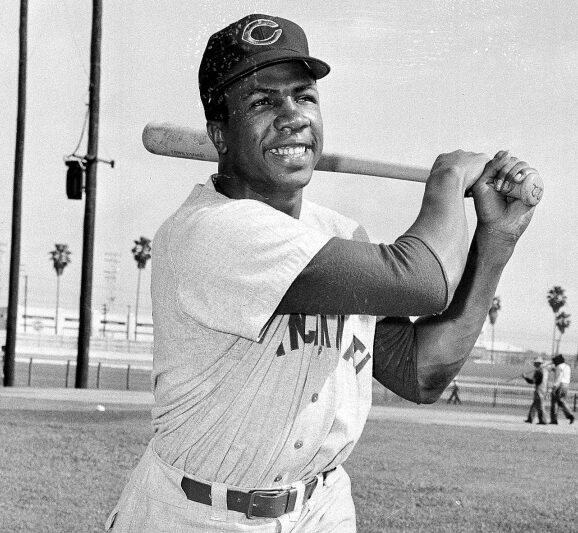

Frank Robinson was remembered immediately for the Hall of Fame baseball player he became over 21 seasons, most notably the first 10 years he spent in Cincinnati and the next six in Baltimore. He was Rookie of the Year, the first to be named MVP in both leagues, a Triple Crown winner, the first black manager – “a Grade-A Negro” player, The Sporting News characterized him upon being traded to Baltimore.

But the descriptors of Frank Robinson as a man made him important rather than merely historic. He was in the vanguard of the liberated black American athlete of the second half of the 20th century. He was in the tip of the spear in their remasculation.

Frank Robinson, who debuted April 17, 1956, in left field at Crosley Field in Cincinnati, wasn’t like black athletes this country championed for most of the first half of the 1900s. He wasn’t like the three most celebrated black athletes in America from World War I through the Korean War – boxer Joe Louis, track and field athlete Jesse Owens and his baseball predecessor Jackie Robinson.

Frank Robinson was like his high school basketball teammate Bill Russell. He was part of the birth in the sixties of black athletes such as Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown and Lew Alcindor, all of whom began to confront their condition as athletic labor and join the civil rights movement, traditional and radical.

He hadn’t planned to be that guy. When Robinson was traded to Baltimore in 1966, the Baltimore NAACP asked him to join. It was reported that he declined unless the organization promised he wouldn’t have to make public appearances while he was a player. But house hunting for him and his family, which included a son and daughter, changed his mind.

As recounted in a Society for American Baseball Research article, Robinson and his wife Barbara thought they found a house until the university professor who was subletting it met Barbara.

“He must have thought I was Mrs. Brooks Robinson,” Frank Robinson’s wife quipped. They wound up in a rental home “grimy and infested with bugs, its floors covered with dog (mess).”

The experience inspired Frank Robinson to change his mind about being active with the city’s NAACP.

In 2008, the Hall of Fame did something it said it never does: It edited Jackie Robinson’s plaque to reflect the history he made reintegrating the major leagues. It should do the same for Frank Robinson.

His most indelible contribution can’t be summed up in statistics, unless they are numbers that somehow take the measure of a man.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story