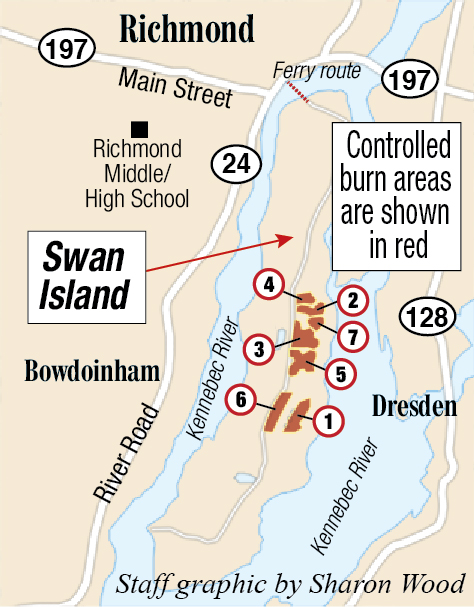

SWAN ISLAND — Wednesday’s controlled burn on the island at the head of Merrymeeting Bay started with drip torch and some burning fuel about 11:30 a.m.

For the next few hours, a crew of Unity College students, state land management workers and volunteers — split into two groups under the direction of a fire boss — systematically set grass fires in open fields on the east side of Swan Island. And then, importantly, they monitored them to make sure the flames did no more than they were intended to do: burn off an accumulation of dead grasses and knock down a number of invasive plant species that have taken root on the island.

John Pratte, a wildlife biologist with the state Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife, said the long-term goal of the fires is to provide habitat on the island for native species of birds such as bobolinks, meadowlarks and Savannah sparrows, some of which have specific nesting requirements that burning the fields will promote. The management plan also is intended to support habitat for several species of butterflies, including the monarch, which is endangered.

“The primary goal is to get rid of the thatch layer,” Pratte said. That’s the layer of last year’s dead grass that carpets the field.

“That builds up and gets too thick, and the birds have a hard time nesting in it,” he said. “It also helps with the invasives and with the ticks.”

The island in the Kennebec River is part of the historic range of those birds. The bobolinks are there in abundance, but Pratte said he hasn’t had time to check and see whether the meadowlarks have returned, or sparrows.

Two years ago, Inland Fisheries & Wildlife launched a plan to burn off the fields in sequence on Swan Island. Pratte said the cycle of burning off all the fields will take eight years to complete; and when it’s done, it will start all over again.

Accelerant flows from a drip torch to ignite more of a field during prescribed burn on Wednesday in the Steve Powell Wildlife Management Area on Swan Island. Kennebec Journal photo by Joe Phelan

The fire boss, John Leavitt, of Burning Alternatives Prescribed Fire Services, looked over the fields that had been burned in prior years with an experienced eye and noted the changes in those areas on his way to the this year’s burn site in the middle of the island.

While some ecosystems, such as those in the West, have evolved with fire, Pratte said few of those exist in Maine. Even so, he said, fire is an efficient tool to clear fields in a management plan.

Even before he stepped onto the island, Leavitt, who was contracted for the job, had spent hours planning and reviewing the site and notifying officials in both Lincoln and Sagadahoc counties about the burn. That work continued with the assembled teams as Leavitt explained how the burn would work, reviewed safety precautions and radio protocols and did a survey of the skills and experience levels of the teams.

After a survey of the planned burn site, the crews were ready before the weather was.

On Wednesday the fire danger for Maine was high or very high, meaning conditions were good for fire. But other factors, such as wind speed, relative humidity, fuel moisture and how wet the ground was would also play a role in the success of the plan.

After the test burn, the teams split apart to spread the fire across two arms in the field; but one stretch, running along the eastern shore of the island, proved too wet to burn, so it was abandoned.

Until the 1940s, Swan Island was home to settlers who farmed and cut ice. At one time, it incorporated as Perkins and was connected to the mainland via ferry. Those settlers brought with them some of the plant species are that are now considered invasive, such as honeysuckle and some roses, or the opportunity for others such as swallow-wort to take root. Swallow-wort can grow in masses of vines and choke out native species.

A worker with a drip torch spreads fire across a field during prescribed burn Wednesday in the Steve Powell Wildlife Management Area on Swan Island. Kennebec Journal photo by Joe Phelan

Eventually, the island was abandoned as the population dwindled and the ferry service ended, leaving behind some buildings, but also cellar holes, foundations and wells.

Pratte said the fire will rejuvenate the fields, which will help the small insects and rodents. The island is also home to deer and moose, as well as coyotes that spend summers on the island and winters on the mainland.

The island also has stands of mature forest. In 2017, about 120 acres of trees were flattened by a freak windstorm that blew through Maine on Oct. 31, leaving more than half the state without electricity for several days to more than a week, depending on the location.

Last year, the state hired a logger to clear that wood from the island.

Pratte said now that those areas have been cleared, he hopes to see changing habitat as the new plants start to grow in. That will help promote the diversity of animal life on the island.

Pratte said the major difference between the fields that have been burned and those that have not will be the absence of invasive species. Once the fire operation wraps up for the year, the fields will start to green up again within about a week as the grass starts to regrow.

As part of a wildlife management area, the island now hosts a variety of recreational and educational activities through the summer, including camping and hiking, and is accessible by ferry. Those activities are expected to start on time this year with indication of the burned acres.

“Last year or the year before, they did aerial imagery right after the burn, and you could see the fields coming back,” he said.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.