A federal judge soon will decide whether to allow two lawsuits against Biddeford police to go forward based in part on new information that police previously declined to disclose in a case that stems from a 2012 double murder.

James Pak, seen in court in 2016, is now serving life in prison for murdering two teenagers and shooting a woman who was his tenant in 2012. Whitney Hayward/Staff Photographer

The lawsuits allege that two Biddeford police officers were negligent for failing to arrest or detain a landlord who shot and killed two teenagers moments after police left his Sokokis Road home. Recent court filings reveal that the officers never asked the landlord, James Pak, if he had a gun, even though he had threatened to shoot one of his tenants in the presence of an officer.

The city of Biddeford has moved for summary judgment in the civil cases brought in 2017 and 2018 in U.S. District Court in Portland by Susan Stevens and Jocelyn Welch stemming from the double murder in an apartment Stevens rented from Pak at the home he occupied with his wife.

Together, the lawsuits allege 21 claims – including intentional infliction of emotional distress, deprivation of constitutional rights, civil conspiracy and due process violations – and seek unspecified damages.

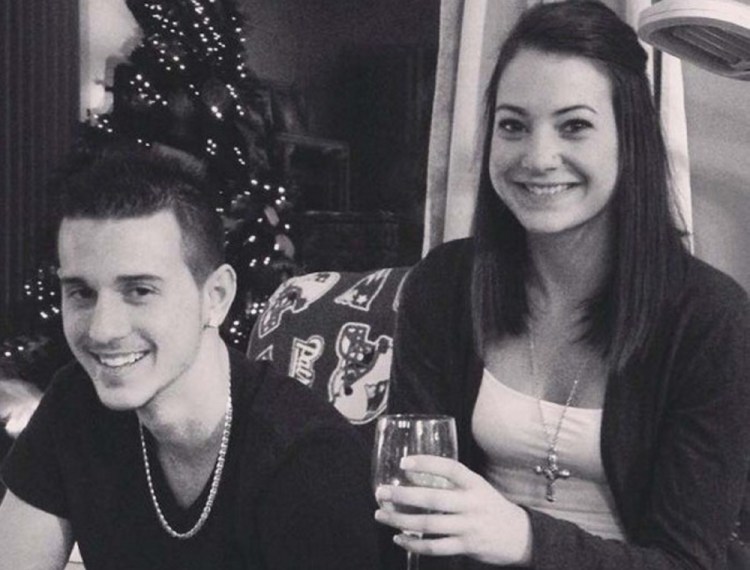

On the evening of Dec. 29, 2012, Pak and Stevens’ son, Derrick Thompson, argued about parking and snow removal at the home, and Stevens called police. Before officers arrived, Pak allegedly threatened to shoot Thompson, and made a gesture with his hand as if it were a gun.

Officers spent about 40 minutes on the scene, talked to both parties and determined that the matter was a civil landlord-tenant dispute and that no crime had been committed, asking each party to stay away from the other.

Minutes after police left, Pak entered the rental unit and shot and killed Thompson, 19, and Thompson’s girlfriend, Alivia Welch, 18. Pak also shot Stevens, seriously wounding her. Stevens went by the name Susan Johnson when she filed the suit.

Pak was arrested about three hours later and admitted to the shootings in interviews with police. Now 81, Pak is serving a life sentence at Mountain View Correctional Center.

Susan Stevens wipes a tear from her cheek as James Pak receives two life sentences in the 2012 murders of her son, Derrick Thompson, and his girlfriend, Alivia Welch, in Superior Court in Alfred on Feb. 11, 2016. Stevens, who was wounded in the attack, is suing the city of Biddeford, claiming police didn’t do enough to prevent the shooting. Whitney Hayward/Staff Photographer

Police later found two other firearms – a rifle and a shotgun – when they searched Pak’s house.

In the recent filings, police acknowledged that Pak had acted strangely but they never asked him if he had been drinking. A breath test following his arrest, almost three hours after the shooting, revealed he had a 0.15 blood alcohol level, nearly twice the legal limit for a driver to be considered intoxicated.

In its recent filings, the city contends that Stevens and Welch fail to meet their legal burdens and misinterpret the applicable case law, and asks that District Judge Jon D. Levy dismiss the case on all grounds.

But attorneys Kristine Hanly and Sarah Churchill, who represent Stevens and Welch, say the city and the two officers should be held accountable for failing to arrest or detain Pak because they misunderstood the criminal statute of terrorizing; allege that the officers did not ask pertinent questions that could have formed the basis for an arrest on a different charge of criminal threatening; and failed to detain Pak based on a department policy aimed at protecting people whose aberrant behavior poses a threat to themselves or others.

According to court records, police asked Thompson if Pak’s threat caused him to be afraid – a required element to bring the charge of criminal threatening. Thompson said “not really,” and was then cut off in conversation by one of the officers, the plaintiffs allege. But police did not ask Stevens or Welch if they felt afraid.

Pak also could have been charged with terrorizing, which involves threats of violence made by anyone against a targeted person, and the natural and probable outcome of those threats is to cause the targeted person to feel credible fear that the crime will be committed.

But the police misconstrued that statute to require the same articulation of fear by the targeted person, the attorneys for Stevens and Welch argue.

Attorneys for Stevens and Welch also say the officers failed to follow a department protocol that requires police to take preventive action against someone who is displaying “deviant behavior,” a broad category of conduct that is not criminal but “creates a condition, either physical or psychological in nature, which presents a threat of imminent and substantial harm to that person or to other persons,” according to the suit.

In such cases, police are permitted to take someone into protective custody, the suit says.

The officers, Edward Dexter and Jacob Wolterbeek, contend that although Pak said he was going to shoot Thompson in front of an officer, Pak wavered on the point and later said he would not shoot Thompson after an officer admonished him against making threats, and that Thompson told police he did not feel in fear of Pak, a critical element if Pak were to be charged with criminal threatening.

The city argues, in part, that the judge should toss the case because police officers enjoy qualified immunity, which protects them from liability for discretionary decisions taken in good faith during the execution of their duties. The decision to arrest is a core discretionary aspect of policing, the city writes, and immunity may only be discarded if the officers’ conduct “was so egregious that it clearly exceeded the scope of any discretion an officer could have possessed in his or her capacity as a police officer.”

The city also argues that the claims fail to meet statutory and precedent-based tests, and that although the outcome for Stevens and her family was tragic, the officers tried to de-escalate the situation and did not create or exacerbate the danger that Stevens and her family ultimately faced or conspire to violate her civil rights.

Allegations that the officers were improperly trained also are invalid, the city argues, because the law requires that a plaintiff show the violation or error was a custom or practice established by police administrators that resulted in the deaths. Both officers were trained in how to handle disturbed or emotionally unstable people, and landlord-tenant disputes.

Issues about the police role in subsequent crimes have come before the courts before, the city argues, and in turn, police have been found not to be responsible for the actions of others, unless in very specific circumstances.

“Officer Edward Dexter and Officer Jacob Wolterbeek were doing their jobs,” wrote Boston attorney Douglas I. Louison, who is representing the city and the officers. “Their discretionary decisions in the circumstances were not conscience shocking. They were decisions which are questioned only in the clear and unfortunate hindsight of this case. … Police officers must make discretionary decisions over the course of their careers which have implications in the lives of others.”

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.