Elza Soares, who rose from the slums of Rio de Janeiro and became one of Brazil’s most popular singers of all time by fusing the traditional samba with bossa nova, Afro-Cuban, pop, soul, jazz and even punk sounds, died Jan. 20 at her beachside home in Rio. She was 91.

Her family announced the death but did not give a cause. They said she had been planning a new album and live performances.

Known throughout Brazil simply as Elza, she developed a reputation as an indomitable grand dame of song, a survivor who had been married off by her parents at 12, was a widow who had buried two of her children by 21, had a long, tempestuous and complicated marriage to Brazil’s soccer great Garrincha, and conveyed through song an ever-hopeful, ever-lustful embrace of life.

As one of the few Black women singers in Brazil to achieve renown – one of her earliest albums was called “A Bossa Negra” – she often fought in her lyrics for equal rights for women (especially those suffering from domestic abuse), Blacks and those in the LGBT community.

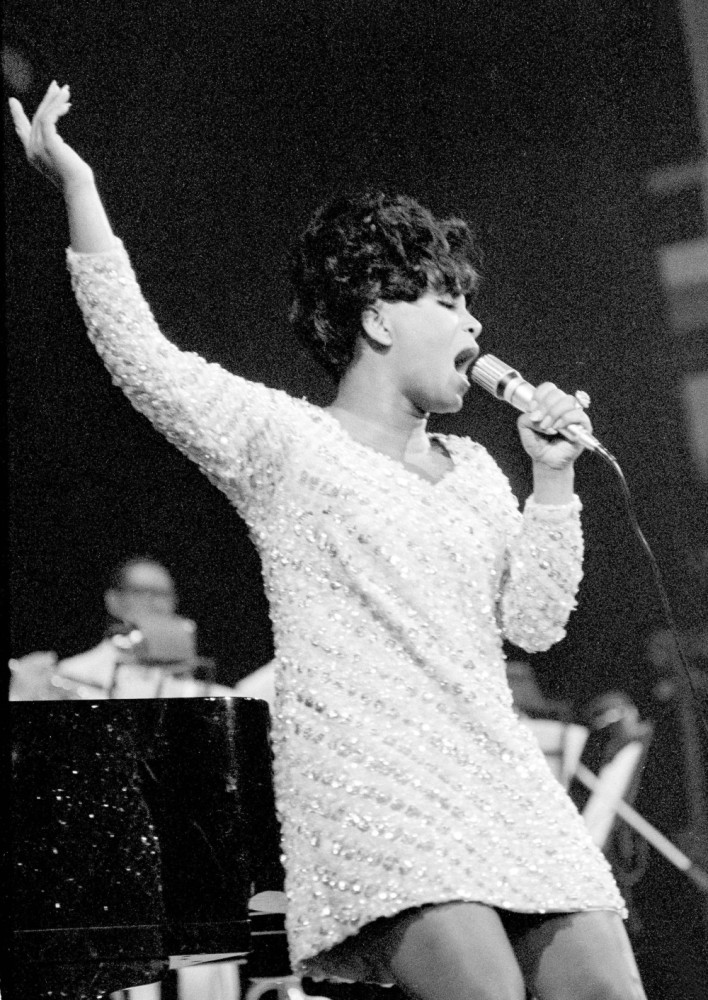

Over seven decades, she recorded 35 albums and sang at the Opening Ceremonies of the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio. Her husky voice was often compared with those of Eartha Kitt, Billie Holiday and Tina Turner as well as Louis Armstrong, with whom she performed several times and from whose vocal style she developed her own form of samba scat.

As much as her voice, she was known for her flamboyant makeup, extensive plastic surgery, gigantic wigs and outrageous dress style, which rivaled any of the dancers or performers at Rio’s renowned annual Carnival.

Soares endured a commercial lull in the 1980s and ’90s following her passionate but ill-fated affair and marriage to Manuel (Mané) Dos Santos, known worldwide by his nickname Garrincha (Little Bird), who often ranked a close second to Pelé in popularity.

Soccer is on a par with religion in Brazil and, like Pelé, Garrincha, known for his asymmetrical legs, was considered a God of the sport. When she and Garrincha met in the early 1960s, he was married and had 10 children. Brazilians, overwhelmingly conservatively Catholic, turned against her as a “homewrecker.”

Described even by friends as a wife-beater, sex addict and alcoholic, Garrincha was drunk in 1969 when he crashed his car. He survived but his passenger, Soares’s mother, did not. The marriage ended in 1982, and the soccer hero died the next year of cirrhosis of the liver – complications from alcohol abuse – at age 49. Their son Manoel died in 1986, age 9, also in a car accident at which a family friend was at the wheel.

Brokenhearted, she spent four years in Los Angeles, halfheartedly trying to revive her career without success. Yet when she spoke, rarely, of Garrincha, it was with fondness. “He gave me my first Billie Holiday album,” she told the Daily Telegraph in 2004. “He brought to the pitch his skills as a samba dancer. He was pure ballet on the field.”

Back in Rio, her career was revived in 1999 when, while singing in a churrascaria (barbecue restaurant, bar and nightclub), she met Jose Gonzaga Araujo, who became her manager. That same year, she was invited to perform in a show called “Since Samba Has Been Samba” at London’s Royal Albert Hall, reuniting leading Brazilian musicians from the 1970s when they sang and protested against the military dictatorship.

She reportedly dazzled and delighted her audience, including many Black Britons, and re-attracted producers and composers. Her later music became known as samba suja, or dirty samba, fusing traditional Brazilian dance music with angry punk.

In 2003, she recorded the album “Do Cóccix Até o Pescoço” (“From the Coccyx to the Neck”), which included an anti-racism song by Brazilian artist Seu Jorge called “A Carne” (The Meat), with the lyrics “The cheapest meat on the market is black meat,” which became one of her most requested tracks.

“Brazil is the most racist country we’ve got,” she told Brazil’s O Globo TV channel on the eve of her 90th birthday. “Things here are awful, it’s an illness with no cure, an absurd situation, disgusting.”

In 2016, her work “A Mulher do Fim do Mundo” (“The Woman at the End of the World”) won a Latin Grammy for best Brazilian popular music album. The next year, at 86, Soares took the stage at New York’s Central Park, as part of the annual Brasil SummerFest to drum home her message of racial and gender equality to rapturous applause.

Elza Gomes da Conceição was born in a Rio favela, or slum, known as Moça Bonita on June 23, 1930. Her father was samba-loving bricklayer, and her mother washed neighbors’ clothes for a living.

As was common in the slums of the time, her father betrothed her to marry a much-older man called Lourdes Antônio Soares when she was 12. She was widowed by 21 after having had five children, two of whom died of hunger.

In 1953, she entered a radio talent show hosted by a prominent samba composer and presenter, Ary Barroso, who commented on her muddy shoes. “Meu amor [my love], what planet did you come from?”

“The same planet as you, sir, Planet Hunger,” she replied.

She won the contest.

Among Soares’s survivors are four children as well as many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Over the decades, profiles emphasized Soares’s teasing and inexhaustible energy onstage and off.

When a Washington Post reporter met Soares at her home in Rio in 2002, he found her in a black catsuit and self-admiring how it fit her derriere after a fitness regimen of weightlifting for two hours every day of the week. She was then in her early 70s and dating an aspiring actor more than 50 years her junior.

“Hey, sweetie, look up here,” she called to him as he fished by her private dock. “Give us a wave, darling.” She then turned to the reporter. “Oh, success has its advantages. . . . He’s hot, I’m hot. We’re all hot now, baby. Now more than ever.”

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.