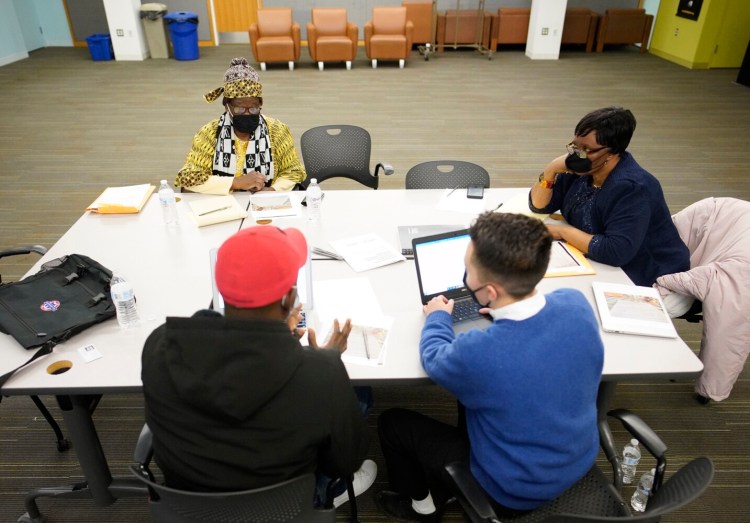

Huddled around a conference table in the basement of the Portland Public Library, on a recent Friday morning, surrounded by laptops, paper, pens and bottled water, small groups of residents worked through thorny transit issues.

Public bus routes that don’t run where and when people need them. Transit information that is unintelligible to those with limited English language skills. Unmet issues of safety and accessibility around buses and bus shelters.

The group, 21 people from Greater Portland, is the latest class of “community transportation leaders,” as they are known, working on from-the-ground-up policy solutions to the regional public transit system’s problems. The program is designed to bring the views and concerns of underrepresented people to decision-makers and train participants in ways to stay informed and involved.

Rustam Ahmadov listens to Kat Violette while they work at creating a presentation to highlight issues with public transportation at the Portland Public Library on Friday. Violette is an outreach and communications associate with GPCOG. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

Rustam Ahmadov joined the group to advocate for an expanded bus route that would better connect his West Falmouth neighborhood to jobs, stores and schools. Depending on the schedule, getting to and from a bus means a two-mile walk down a street without a sidewalk, said Ahmadov, 17.

Identifying a problem is one thing; solving it is another.

“You know the issue, but it’s not like you can just tell the bus driver,” Ahmadov said. “You have to go a little higher.”

Through the program, Ahmadov and his colleagues get coaching to develop their priorities into presentations to regional transportation decision-makers. The group projects focus on individual participants’ goals, broader improvements to regional transit and how to connect with people facing similar issues.

“You learn how to present it in a professional way so your voice and the voices of your community are heard,” Ahmadov said.

IDEAS ‘WANTED AND NEEDED’

Layers of bureaucracy and budgeting surrounding public transit can be hard to decipher for many people, especially those who are disadvantaged by a disability, low income level or cultural and language barriers. But those are often the very same people who rely on public transit and know its problems and weaknesses, said Kat Violette, a program organizer at the Greater Portland Council of Governments, or GPCOG.

“People in the program want to make changes, but they come in not knowing what is going on,” Violette said. “We are reminding people and telling people that their opinion is wanted and needed, and that is how we make transportation equitable for the people that need it.”

On Friday, groups practiced presentations to be given this week to the executive committee of the Portland Area Comprehensive Transportation System, a regional planning body that directs $25 million annually in federal funding.

Alongside Ahmadov was Bill Higgins, 62, who proposed extending a bus route to Cape Elizabeth to connect that town to Greater Portland. Sandi Shubert wanted to address recent changes to her regular bus route to The Maine Mall in South Portland. One day, without warning, her regular route set her down in an unfamiliar spot, forcing the 77-year-old to navigate her walker across a massive parking lot and five-lane road to get to her destination.

“It’s good to know you have a say,” Shubert said.

Marie-Immaculee Kabazo talks through an interpreter while discussing a presentation her group is creating to highlight issues with public transportation at the Portland Public Library on Friday. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

Later in the morning, Marie-Immaculee Kabazo and Melanie Atia Sedua drafted a proposal for added information and signage for riders with limited English skills. The two Congolese women, speaking through a French language translator, said it was hard to figure out the stops or bus routes when they moved to the Portland area, and that information for non-English speakers was scant. Signs showing route maps at bus stops and indications of upcoming stops for bus riders were solutions they proposed.

Greater Portland Metro, the region’s largest public bus service, offers brief online guides in six languages for how to use the local bus system, but most of its signage and route information is in English.

GETTING MORE VOICES HEARD

This is the second group to graduate from the program. The first group included two people who now sit on GPCOG’s Regional Transportation Advisory Committee, a body that guides the planning group’s transit and mobility work.

“As an immigrant, you can use your voice and bring change to the transportation system,” said Guy Mpoyi of Westbrook, a graduate of the first leaders’ course. Mpoyi remains involved as a liaison to new students of the program and helped establish a transportation ambassador program with Metro to help explain the transit system to new Mainers.

“The program gave me the opportunity to speak to who is in charge and tell them what the problems are and share our ideas on how to make it better,” Mpoyi said.

Melanie Atia Sedua looks over a printout while participating in a session to create a presentation highlighting issues with public transportation at the Portland Public Library on Friday. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

The local training course is a “sterling example” of inclusive planning that brings in perspectives of people frequently disenfranchised in public transit, said Charles Rutkowski, assistant director of the Community Transportation Association of America. The organization funded the Portland-area project through a federal grant.

Transit agencies and government funders often present services intended to assist disadvantaged people, including the elderly and disabled, without soliciting their guidance and input, Rutkowski said.

“Very often, unless those people are involved in designing, planning and rolling out services, those services may not be responsive to those individuals’ needs,” Rutkowski said.

It’s a symbiotic issue – people may see issues with their local bus route but feel they don’t have a voice or can’t make a change. At the same time, well-meaning managers and policymakers may also be several layers away from everyday transit riders and insulated from their concerns and issues.

“There is a lack of connection from both sides,” Rutkowski said. “By deliberately involving the user in the process, they are connecting the management, the riders and the policymakers. It is breaking down the barriers that interfere with that collaboration.”

Correction: This story was updated at 6:30 a.m. Tuesday, Feb. 22, 2022, to correct a misspelling of Guy Mpoyi’s last name.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story