WASHINGTON — The more we study animals, the less special we seem.

Baboons can distinguish between written words and gibberish. Monkeys seem to be able to do multiplication. Apes can delay instant gratification longer than a human child can. They plan ahead. They make war and peace. They show empathy. They share.

“It’s not a question of whether they think — it’s how they think,” said Duke University scientist Brian Hare.

Now scientists wonder if apes are capable of thinking about what other apes are thinking.

The evidence that animals are more intelligent and more social than we thought seems to grow each year, especially when it comes to primates. It’s an increasingly hot scientific field with the number of ape and monkey cognition studies doubling in recent years, often with better technology and neuroscience paving the way to unusual discoveries.

This month, scientists mapping the DNA of the bonobo ape found that, like the chimp, bonobos are only 1.3 percent different from humans.

Said Josep Call, director of the primate research center at the Max Planck Institute in Germany: “Every year we discover things that we thought they could not do.”

Call said one of his recent more surprising studies showed that apes can set goals and follow through with them.

Orangutans and bonobos in a zoo were offered eight possible tools — two of which would help them get at some food. At times when they chose the proper tool, researchers moved the apes to a different area before they could get the food, and then kept them waiting as much as 14 hours.

In nearly every case, when the apes realized they were being moved, they took their tool with them so they could use it to get food the next day, remembering that even after sleeping. The goal and series of tasks didn’t leave the apes’ minds.

Call said this is similar to a person packing luggage a day before a trip: “For humans it’s such a central ability, it’s so important.”

For a few years, scientists have watched chimpanzees in zoos collect and store rocks as weapons for later use. In May, a study found they even add deception to the mix. They created haystacks to conceal their stash of stones from opponents, just like nations do with bombs.

Hare points to studies where competing chimpanzees enter an arena where one bit of food is hidden from view for only one chimp.

The chimp that can see the hidden food, quickly learns that his foe can’t see it and uses that to his advantage, displaying the ability to perceive another ape’s situation. That’s a trait humans develop as toddlers, but something we thought other animals never got, Hare said.

And then there is the amazing monkey memory.

At the National Zoo in Washington, humans who try to match their recall skills with an orangutan’s are humbled. Zoo associate director Don Moore said: “I’ve got a Ph.D., for God’s sake. You would think I could out-think an orang, and I can’t.”

In French research, at least two baboons kept memorizing so many pictures — several thousand — that after three years researchers ran out of time before the baboons reached their limit.

Researcher Joel Fagot at the French National Center for Scientific Research figured they could memorize at least 10,000 and probably more.

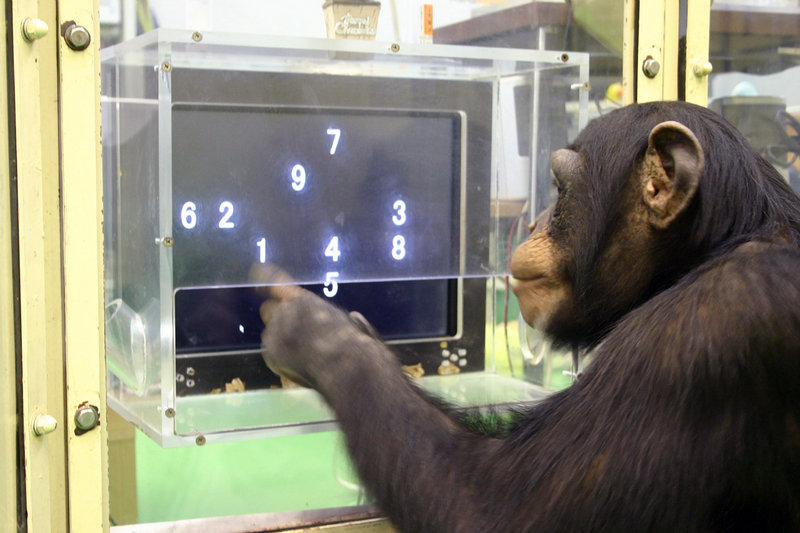

And a chimp in Japan named Ayumu who sees strings of numbers flash on a screen for a split-second regularly beats humans at accurately duplicating the lineup.

He’s a YouTube sensation, along with orangutans in a Miami zoo that use iPads.

It’s not just primates that demonstrate surprising abilities.

Dolphins, whose brains are 25 percent heavier than humans’ brains, recognize themselves in a mirror. So do elephants. A study in June found that black bears can do primitive counting, something even pigeons have done, by putting two dots before five, or 10 before 20 in one experiment.

The trend in research is to identify some new thinking skill that chimps can do, revealing that certain abilities are “not uniquely human,” said Emory University primatologist Frans de Waal. Then the scientists find that same ability in other primates further removed from humans genetically. Then they see it in dogs and elephants.

“Capacities that we think in humans are very special and complex are probably not so special and not so complex,” de Waal said. “This research in animals elevates the animals, but it also brings down the humans. … If monkeys can do it and maybe dogs and other animals, maybe it’s not as complex as you think.”

At Duke, professor Elizabeth Brannon shows videos of monkeys that appear to be doing a “fuzzy representation” of multiplication by following the number of dots that go into a box on a computer screen and choosing the right answer to come out of the box. This is after they’ve already done addition and subtraction.

This spring in France, researchers showed that six baboons could distinguish between fake and real four-letter words — BRRU vs KITE, for example. And they chose to do these computer-based exercises of their own free will, either for fun or a snack.

It was once thought the control of emotions and the ability to empathize and socialize separated us from our primate cousins. But chimps console, and fight, each other. They also try to soothe an upset companion, grooming and putting their arms around him.

“I see plenty of empathy in my chimpanzees,” de Waal said. But studies have shown they also go to war against neighboring colonies, killing the males and taking the females. That’s something that also is very human and led people to believe that war-making must go back in our lineage 6 million years, de Waal said.

When scientists look at our other closest relative, the bonobo, they see a difference. Bonobos don’t kill.

Hare said his experiments show bonobos give food to newcomer bonobos, even when they could choose to keep all the food themselves.

One reason scientists are learning more about animal intellect is computers, including touch screens. In some cases, scientists are setting up banks of computers available to primates 24-7. In the French word recognition experiment, Fagot found he got more and better data when it was the baboons’ choice to work.

Animal cognition researcher Steve Ross at the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago agreed.

“The apes in our case seem to be working better when they have that control, that choice to perform,” he said.

Brain scans on monkeys and apes also have helped correct mistaken views about ape brain power. It was once thought the prefrontal cortex, the area in charge of higher reasoning, was disproportionately larger than the rest of the brain only in humans, giving us a cognitive advantage, Hare said. But imaging shows that monkey and ape prefrontal cortexes have that same larger scale, he said.

What’s different is that the human communication system in the prefrontal cortex is more complex, Hare said.

So there are limits to what non-human primates can do.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.