WALPOLE – This time of year, Damariscotta River oyster growers usually kick back and relax.

The river is covered with a thick crust of snow and ice, and the oyster beds underneath lie dormant.

But this year, many are finding it hard to take it easy. A disease that decimated the Chesapeake Bay oyster fishery showed up for the first time last summer in the Damariscotta, the site of Maine’s most productive oyster beds.

Now the river’s 24 leaseholders are wondering what damage the disease, known as MSX, has done over the winter.

“Historically, when MSX has been found, it tends to persist,” said Chris Davis, co-owner of Pemaquid Oyster Co. and director of the Maine Aquaculture Innovation Center.

The disease, which is spread by Haplosporidium nelsoni, a single-celled parasite, is harmless to humans but deadly to the American oysters cultivated in the Damariscotta.

The disease was first detected in the United States in Delaware Bay in 1957 and is believed to have arrived from oysters introduced from the Pacific Ocean. Two years later, it showed up in lower Chesapeake Bay, where it quickly spread to 90 percent of the oysters.

It was always thought that Maine waters were too cold for the parasite to take hold — until last July. That’s when dead oysters began to show up in the holding rafts, where they are stored for a couple of weeks of de-silting after being harvested from their muddy beds farther up the river.

By mid-August, the growers sent their oysters off for testing and got the bad news that MSX had moved into the river, the state’s breadbasket when it comes to oyster farming.

The river is perfectly suited to oysters, said Marcy Nelson, a scientist at the Department of Marine Resources.

Great Salt Bay, which lies at the head of the river north of the Route 1 bridge at Damariscotta and Newcastle, provides a rich source of phytoplankton, on which oysters feed. The water in the upper river is warm, so the oysters grow plumper more quickly than in other Maine rivers.

American oysters raised on the Damariscotta account for 63 percent of the state’s annual cultivated harvest, which has fluctuated between 1.6 million and 3.6 million pieces annually, worth an estimated $3 million to $5 million to the growers.

A Damariscotta oyster can fetch up to $5 on the half shell at the toniest raw bars in Los Angeles and other big cities, said James King, in sales and marketing at JP Shellfish in Eliot.

“These are premier oysters,” he said.

Oyster farming on the Damariscotta grew out of research being done at the University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center in Walpole 30 years ago, when the bivalve had disappeared from the river for unknown reasons. But the towering shell middens left on the shoreline by feasting Indians 2,000 years ago attested to the once-bountiful supply of the mollusks.

Davis, of Pemaquid Oyster, who earned his doctorate at the University of Maine doing oyster research, was among the earliest to start an oyster aquaculture operation on the river in the 1980s. Today, there is little available space left for lease.

Once the presence of MSX was confirmed, Davis and other growers quickly initiated a quarantine of the oysters with the help of the Department of Marine Resources, to prevent diseased oysters from being moved into other areas and spreading the infection.

No one knows why MSX hit the river last summer, but many blame the previous warm, dry winter followed by a string of record high temperatures and higher salinity levels in the river.

“MSX does not like fresh water,” said Nelson.

Just how the parasite spreads remains a mystery.

Researchers at the Department of Marine Resources and the University of Maine Cooperative Extension tested farmed and wild oyster beds in other areas of the state and found the disease in the upper Sheepscot River and upper New Meadows River, but at much lower levels. The strain found in these two rivers also appears to be different from the strain in the Damariscotta River.

Nelson said that leads the researchers to believe that MSX was introduced to the Damariscotta River through human activity, rather than traveling naturally up the coast from the south.

“It is unlikely we will ever know the exact source of the MSX outbreak in the Damariscotta,” she said.

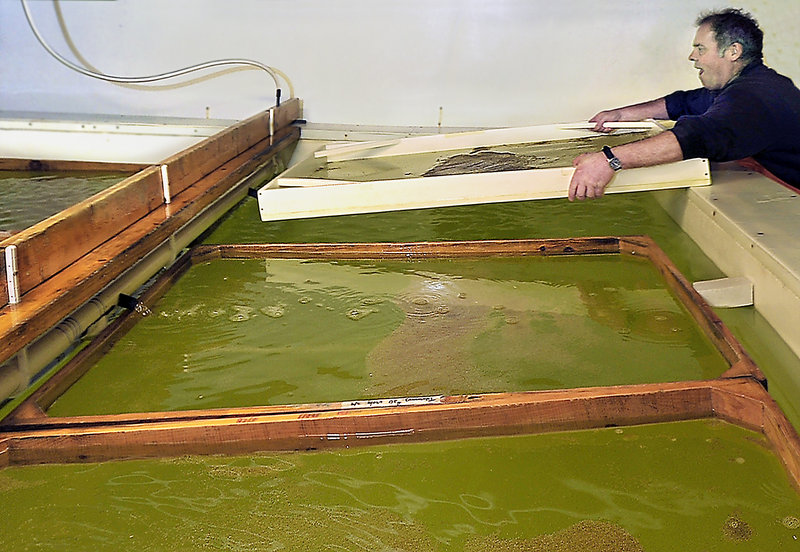

There is no cure for the disease, but various strains of American oysters have been developed with higher levels of resistance. And there is a local supply of disease-resistant oyster seed — tiny oysters transplanted to another location for the purposes of commercial raising or bed restoration — at Mook Sea Farm in Walpole.

Ironically, the hatchery turns out 50 million MSX-resistant oyster seeds annually for other parts of the country that have been hard hit by MSX. But because it was assumed that Maine waters were immune, the disease-resistant strains were not being used locally, not even by Bill Mook, hatchery owner.

Mook, whose Wiley Point oyster farm harvests 400,000 to 500,000 oysters a year, said he lost several hundred thousand dollars last season to MSX.

“We took a big hit,” said Mook.

This year, Mook is cranking up his hatchery production, in part to meet increased demand for the disease-resistant seed. He said the seed growing today at his hatchery will be sown this spring and ready for harvest in 12 to 14 months.

The University of Maine is also working on a disease-resistant strain.

Some of the Damariscotta’s farmers say they are waiting until the ice melts, usually sometime next month, before deciding what course of action to take. It is also possible a very cold winter could reduce the level of MSX infection this summer.

“We are an industry of bright, ambitious people who think outside of the box. If there is any industry in the world, this industry can figure its way around this roadblock,” said Barb Scully, owner of Glidden Point Oyster Co. in Edgecomb.

Staff Writer Beth Quimby can be contacted at 791-6363 or at:

bquimby@pressherald.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.