MINNEAPOLIS – New lawyer John Kay was ready for the fast track. He had graduated from Pepperdine University with honors. He speaks fluent Korean and is proficient in Mandarin Chinese.

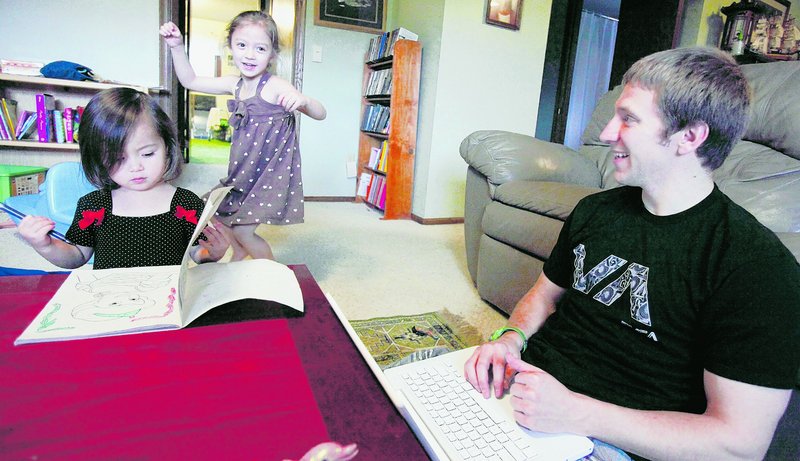

But a year after graduating, he lives with his wife and young kids in his parents’ Prior Lake, Minn., basement. The $160,000-a-year job that a big Los Angeles firm offered him when he was in school disappeared during the economic downturn. He surfs the Internet for jobs while his wife works and his daughters nap.

He hopes a job comes before he must start repaying $100,000 in student loans.

A few years ago, a law degree was practically a ticket to a comfortable life. The recession has changed that for most new graduates. Demand may be up for defense attorneys for white-collar thieves, but mergers and acquisitions are down, and corporations have trimmed legal budgets. Older lawyers postponed retirement, and most firms have less to do.

This week, law schools in Minnesota and beyond are sending graduates into the grimmest job market in decades. “I thought I had really hit the big time,” Kay said. “Now the big joke is: ‘You’ll be lucky if you retire making (what) they offered you to start.”‘

Websites such as abovethelaw.com and minnesotalawyer.com are rife with discussions under headlines such as, “Those jobs are going, and they’re not coming back.” The sites ask whether a law degree is still worth the expense. School administrators say it is, but they add that today’s graduates need to search harder and perhaps longer for good jobs.

The University of Minnesota Law School’s website claims 97 percent of the class of 2008 got jobs in their field and 99 percent of graduates do after five years. Recent grads groan that those numbers include jobs such as reviewing documents for a legal temp agency. Some say even those jobs are hard to get.

“I have no problem paying my dues,” Kay said. “The problem is, I can’t even get a job at the bottom.”

The National Association for Law Placement on Thursday released a survey showing an overall employment rate of 89 percent of 2009 graduates for whom status was known. That’s 3 percentage points below 2007’s historic high and the lowest rate since the mid-1990s. The group noted that the new number reflects increases in temporary and part-time employment.

HIRING HAS DECREASED

In good times, top law students were almost guaranteed good jobs based on first-year grades and their experience as summer associates. In the recession, bigger firms decreased hiring by about half, said Mark Greiner, hiring partner at Fredrikson and Byron in downtown Minneapolis. His firm hired seven students for the summer, with plans to take them on permanently after they graduate. That’s about five fewer than before the recession, Greiner said.

Greiner graduated 20 years ago and said the current market is the worst he has seen. Adding to pressure in Minnesota has been the return of young lawyers who lost jobs on the coasts, where firms were hit harder.

For top graduates, the profession is still “an embarrassment of riches,” Greiner said. But he added that just a notch below them, “even good students are having a tough time.”

Matt Nelson graduated last week from the University of Minnesota with a law degree and an MBA. Nelson, 36, was on track to earn $145,000 his first year at a Milwaukee firm. But duty called, and while he was serving as an Army paralegal in Iraq, Milwaukee withdrew its offer.

“A lot of law students have a romantic vision of what they’re going to do when they go to law school, but I’m not bitter,” said Nelson, who also is a software engineer. “A lot of people are suffering.”

Bridgid Dowdal, assistant dean for career and professional development at William Mitchell College of Law in St. Paul, said graduating is no longer enough. Students must network, volunteer at legal clinics, intern for firms and clerk for judges, Dowdal said, adding that a good attitude is a huge plus.

“Do I see a grim future? Not for the people who are real hustlers,” she said.

NOT BUYING A TOASTER

Darcy Sherman, 32, directed a trial clinic at the University of Minnesota before graduating in 2008. She had been a fraud investigator. She wants to be a prosecutor, but jobs are scarce in the public sector, too. She wishes she had had the benefit of a realistic cost-benefit analysis before going to law school.

“I can find information on a $15 toaster, but if you want to go $100,000 in debt, there’s no information,” she said.

After a year of part-time work, she landed a job earning $41,000 as a judge’s clerk. For her, the jury is still out on whether going to law school was smart.

“I hope I have a definitive answer in 10 years, where I say, ‘Oh, this is great. I love what I do,”‘ she said.

STARVING EDUCATION

School administrators insist a law degree remains a good long-term investment.

Niels Schaumann, vice dean for faculty at Mitchell, said: “The more urgent question is: What do you tell people who are thinking about going to law school? I don’t recommend it to people looking to make a lot of money. … If you’re not interested in helping people in some way or providing service to your clients, it’s not for you.”

Both he and David Wippmann, dean at the University of Minnesota Law School, question how long tuition can continue to rise. Wippmann said state support for its only public law school has declined. “I think there should be a broad public policy discussion about where we should be directing resources,” he said.

Minnesota Supreme Court Justice Paul H. Anderson said something’s gone wrong since he graduated in 1968 with no debt and a 1965 Mustang. “The generation before me came to the conclusion I was worth the investment,” he said. “Maybe my generation is a little too selfish.”

Anderson concedes lawyers aren’t likely to get a ton of sympathy, but he says their plight warns of a bad trend in education: “We are into a model now where we are starving education and then blaming it when it doesn’t perform,” he said.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.